I’ve spent a lot of time lately talking to safety leaders about the “Safe Systems Approach.” Or, more accurately, I’ve been talking about what safety leaders think “Safe Systems” means.

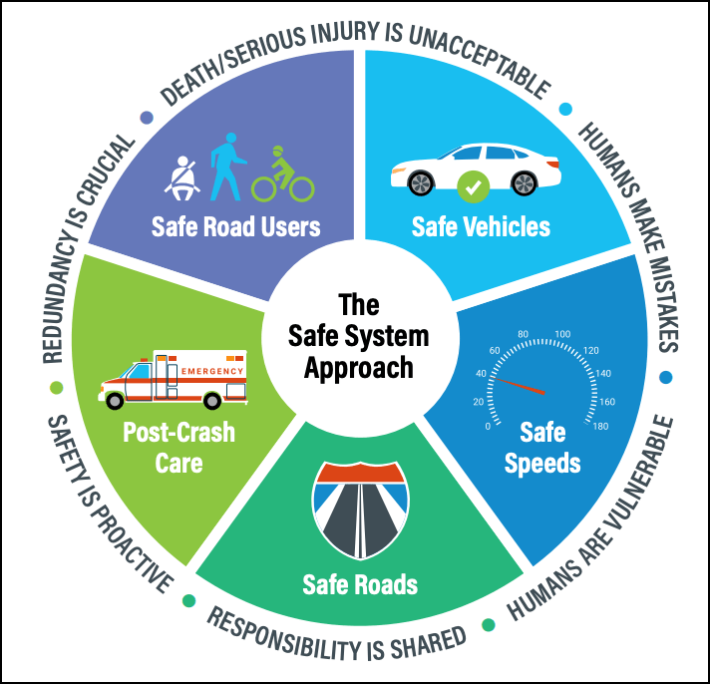

As the U.S. Department of Transportation celebrates the two-year anniversary of adopting the National Roadway Safety Strategy — and as New York City celebrates 10 years since it became the first U.S. city to embrace the Vision Zero goal that the Safe Systems approach is meant to achieve — I have been positively mired in press conferences and interviews about the famous road safety model, which promises to end car crash deaths and serious injuries by investing in five sectors: safe roads, safe speeds, safe vehicles, safe road users, and safe post-crash care.

For weeks, I have listened to politician after DOT leader after nonprofit policy director wax on about why it’s so great that America has, at long last, accepted that the 43,000 annual road deaths can and must be prevented through systemic interventions, rather than treating traffic violence solely as the fault of individual road users who make bad choices like speeding or jaywalking — or worse, as random acts of God.

Sure, pedestrian deaths remain stubbornly on the rise. Yes, there’s “more work to be done.” But at least we have finally accepted that safety is our “shared responsibility” — to quote AASHTO President Jim Tymon at a recent DOT presser — and we’ve all, finally, pledged to do our part.

The trouble with “shared responsibility,” of course, is that it says nothing about our respective ability to save lives — or how that “responsibility” should be shared relative to our respective power and influence.

I’m far from the first sustainable transportation advocate to point this out.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen a fellow advocate patiently explain that a kindergartener on a bike has far less “responsibility” or ability to avoid being killed by a driver in an SUV than a driver has the responsibility to pay attention to the road, or a road designer to protect the bike lane she’s in, or a NHTSA administrator to mandate a maximum size for the SUV to reduce the likelihood that it will kill.

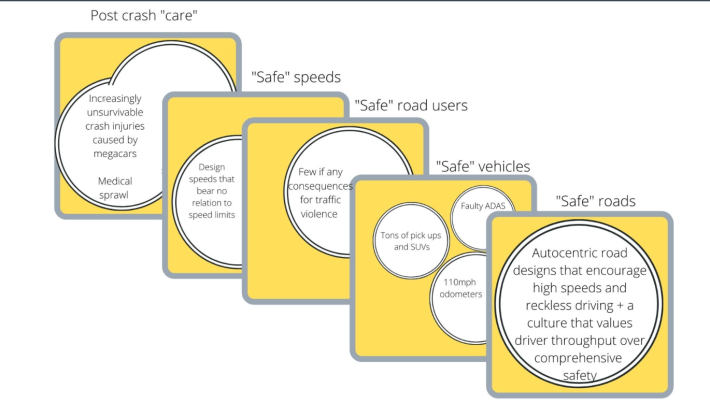

In a truly Safe System, the kindergartner’s “responsibility” to wear a helmet — which for a raft of well-studied reasons, we shouldn’t impose on her anyway — should be the absolute last in a cascading series of safety nets, deliberately arranged with the strongest layers at the top. In a truly safe system, we should recognize that when someone like a small child is involved, the “safe road users” net is essentially made out of gossamer, so the other, higher layers better be made out of increasingly dense steel mesh.

A lot of American safety professionals, though, seem to think of the Safe Systems approach not like a series of carefully engineered safety nets of wildly different tensile strengths, but like a single safety net with five equally sized panels stitched precariously together. And when all of those panels are too frayed to keep anyone aloft, our leaders are quick to say that someone should reinforce them – safety is their first priority, after all — though no one ever seems to take responsibility for doing it with any urgency. And no one seems to believe that the gaping holes in their fabric panel are the biggest problem.

That’s increasingly apparent to me as the entire industry pats themselves of the back for two years of national commitment to “Vision Zero.” In the last week alone, I’ve heard powerful people argue, unironically, that pedestrians should wear retro-reflective clothing to do their part towards supporting the “safe road users” slice of the pie. I’ve seen DOT heads (who collectively spent 25 percent of their most flexible federal funding towards highway expansions rather than safe infrastructure) brag about creating ads urging drivers to buckle up and put their phones down.

USDOT has even applauded itself for soliciting a not-exactly-whopping 123 new “commitments” to enhance safety from “Allies in Action” — some of which are simple PSA campaigns, posters to spread “awareness,” and promises from nonprofits to do exactly the same advocacy work they have literally always done. Half of them, by the DOT’s own analysis, are about creating safe road users; 44 are about creating safer roads, 26 are safer vehicles, and only seven are about creating safer speeds.

To be clear: many of the commitments on USDOT’s list will move the needle on U.S. roadway safety — and some of them are significantly more meaningful than posters. And posters aside, not all public awareness campaigns are useless; we do need safer road users, and thoughtfully deployed education campaigns can play a critical role.

What’s even more painfully clear, though, is that the particular “Safe Systems” that America is building are nowhere near sufficient to meet the scale of our roadway crisis.

We have not yet meaningfully reckoned with which layers of that system have the most potential to save lives, and which ones are most subject to failure.

We have not directed anywhere near the resources we need to strengthen our strongest layers before anyone else falls through the cracks.

We have not named the people who have the most power to do that strengthening, or assigned them the appropriate share of responsibility to act.

And we certainly have not acknowledged that all these endless safety nets just aren’t as necessary when Americans are less dependent on cars to meet their every need, or the essential role that simply having fewer drivers can play in preventing driver violence.

It's great — if painfully overdue — that America has finally realized that traffic violence is a systemic problem with systemic solutions. If we can’t advance the conversation beyond that astonishingly low bar, though, the Safe Systems approach will become just another way for powerful people to keep passing the buck to the "safe road users" piece of the puzzle — and the powerless will keep unsuccessfully shouldering the weight of a “responsibility” that they never had any hope of carrying in the first place.