The first American city to adopt a Vision Zero goal has notched major wins and major failures in its quest to end traffic deaths and serious injuries — and other American cities can learn a lot from both the good and bad sides of its track record, a new report argues.

In the analysis, advocacy group Transportation Alternatives surveyed the progress the Big Apple has made in the decade since it became the first major city in the U.S. to embrace the world-renowned Swedish safety model in 2014. And it also detailed how other American cities can replicate New York's successes and avoid its mistakes — regardless of their transportation landscapes.

First, the good news: As pedestrian deaths shot up up 67.4 percent nationally, New York's fell by 29 percent. And overall traffic fatalities were 16 percent lower in the last 10 years than in the decade before Vision Zero took effect.

But the city is nowhere near the "zero" part of Vision Zero; NYC reported 258 traffic deaths last year. (Streetsblog NYC crunched all the numbers here.)

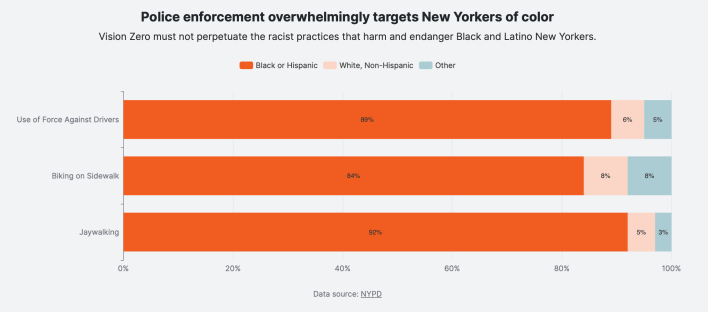

And whatever successes the city has experienced, they weren't spread out equally across New York's famously diverse population: BIPOC and low-income New Yorkers experienced higher rates of force when stopped by police and more road violence no matter how they got around.

Cyclist deaths also fluctuated wildly, ending 2023 with the second-highest number on record as bike trips skyrocketed and local leaders failed to build protected infrastructure to match.

Here are five lessons for communities who want to do even better than the biggest city America, from the advocacy group that helped bring Vision Zero to its shores.

1. Go system-wide or go home

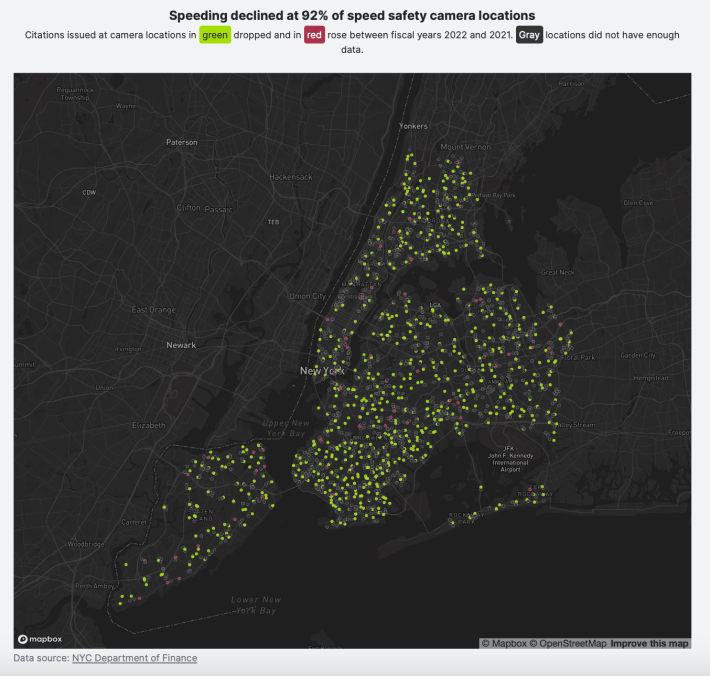

Perhaps New York's single most dramatic Vision Zero win was also one of its first when, in 2014, advocates succeeded in lowering the speed limit to 25 miles per hour — and launched what would soon become the largest automated speed enforcement program in the world.

That simple but dramatic move slashed pedestrian fatalities by 22 percent within a single year, and cut down on overall fatalities by a quarter — even as other U.S. communities rationed similar changes only to corridors with the highest number of crashes, or didn't undertake them at all. The TransAlt team compares that strategy to "an unending game of whack-a-mole" which simply shifts danger from one corridor to the next, rather than sending a message that reckless driving has no place anywhere.

“We didn’t allow the politics or anything else to get in the way of the fact that safety was the most important factor," said the group's Senior Director of Policy and Research Philip Miatkowski. "If pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers are using every street in your city, you should be implementing change on every street in your city.”

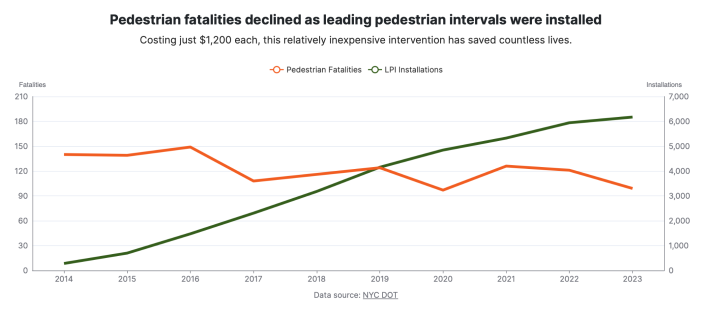

2. Start with the cheap stuff

Miatkowski acknowledged that sweeping, system-wide updates might be a tough sell in smaller communities with fewer resources than America's richest and densest mega-city. Still, he argued that many of New York's most transformative changes were done on the cheap, like reprogramming crossing signals to give pedestrians a head start at the relatively inexpensive cost of just $1,200 per intersection.

The nearby New Jersey city of Hoboken, meanwhile, has had even more success by simply removing parking spaces near corners to improve sight lines. That strategy, known as "daylighting," is one most New York City advocacy groups hope to emulate and improve upon by encouraging New York to replace those former parking spaces with benches, planters, mini-parks, and other things that make street life more vibrant.

“Almost anything is better than a parked car,” Miatkowski said.

And those low-cost safety shifts are certainly better and cheaper than the alternative: letting people die and sustain serious injuries. Despite all its progress, the city Department of Transportation estimates that traffic crashes still cost the city $4.29 billion a year — and they cost America at large more than $340 billion and rising.

3. Invest in 'self-enforcing streets' — not cops

Safe infrastructure could also save American cities money in another department: by reducing the "need" for human officers to police people into using dangerously-designed roads in a safe manner, which studies show doesn't even work a lot of the time.

Unfortunately, TransAlt said New York still has a lot of work to do to achieve that worthy goal. Wealthy, white neighborhoods have enjoyed big-ticket safety improvements during the Vision Zero era — think pedestrian plazas, protected bike lanes and car-free bus lanes — but in communities of color and low-income neighborhoods, the city has heavily relied on enforcement-based strategies instead. In 2022 alone, Black and Latino New Yorkers experienced 92 percent of all traffic summons for jaywalking, as Streetsblog has long documented; they also received 84 percent of summons for biking on the sidewalk, even on streets with no other safe place to ride.

As a result of those two radically different approaches, TA said that "between 2014 and 2020, the most recent year data is available, traffic fatalities for white New Yorkers decreased 20 percent, while traffic fatalities for Latino New Yorkers increased 7 percent and fatalities for Black New Yorkers increased 2 percent." And that's not even counting harassment, serious injuries and fatalities sustained during interactions with police, which studies show are significantly higher for people of color.

“If we create self-enforcing streets designed to prevent speeding and other dangerous movements, and streets that separate pedestrians, bicyclists and drivers, we’ll also create streets where the presence of police won’t be needed as much," added Miatkowski.

4. Stop the PSAs already

Another place where New York — and other cities — could scrounge up more money for infrastructure? From the money currently spent on ineffective safety PSAs that simply ask drivers to be more careful.

TransAlt cited New York's ongoing "Dusk and Darkness" campaign, which advises drivers to be alert in the dark hours following the end of Daylight Savings Time — and tells pedestrians to "do what you can be to be seen" by inattentive motorists.

The $10.5 million the city has spent on the campaign so far could have built more than 17 miles of protected bike lanes, the group estimated.

“Advertising and telling drivers not to hit and kill pedestrians and cyclists is not only ineffective; it’s antithetical to Vision Zero," added Miatkowski. "Saying that crashes are the fault of drivers rather than a lack of infrastructure is an easy out. Unfortunately, that’s what a lot of our culture is based on: focusing on individual behavior rather than fixing systemic issues.”

5. Get with the times

Perhaps the most impactful thing any U.S. city can do to achieve Vision Zero, TransAlt says, is to recognize that the nature of their traffic violence epidemic is always changing — and it's incumbent on leaders to adapt their strategies to respond to new challenges and opportunities.

In New York City, for instance, 10 years of Vision Zero had brought with it an explosion in overall cycling trips along with huge spike in large-format electric and cargo bikes, but city leaders haven't built nearly enough expanded, high-quality bike lanes to match. An explosion in SUV purchases, meanwhile, has corresponded with an explosion in child deaths under the wheels of those megacars, but hasn't inspired bold policy to rein in car bloat and save children's lives.

Those kinds of failures aren't unique to New York, of course — and other cities aren't even bothering to collect the data they need to identify similar issues. If the Big Apple can correct those shortcomings, though, they could become the true Vision Zero leader the country deserves, and provide clear proof of concept this approach should be the norm in every U.S. city.

“There isn’t anything wrong with Vision Zero itself; the program just needs to adapt to a changing city, and it’s going to change even more in the next 10 years," Miatkowski said. "But we know what works; we just need to expand it from pilot to permanent, from just a few city blocks to citywide, and eventually, across America."

Clarification: An earlier version of this story included a statistic from Transportation Alternatives that did not appear, upon further review, to be accurate. We have cut that assertion.