There is almost no evidence that cycling regulations are making U.S. streets safer, and more than enough evidence that they should be overhauled to prevent disproportionately harmful impacts against people of color, a new study finds.

As part of their ongoing update to the Urban Bikeway Design Guide, which sets the standard for active transportation infrastructure in communities across the U.S., the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NATCO) recently issued a new paper about the safety regulations that most commonly govern how people ride, such as laws against biking without a helmet, running stop signs, or traveling against the direction of car traffic.

The researchers say, though, that there's little proof those rules actually reduce traffic violence or crash severity — and that the very act of enforcing them is putting riders in danger, particularly when they belong to racially marginalized groups.

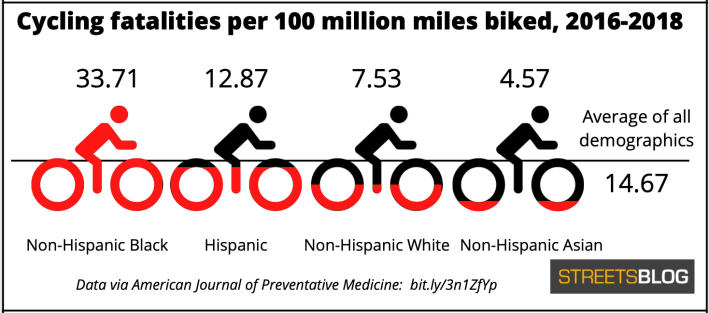

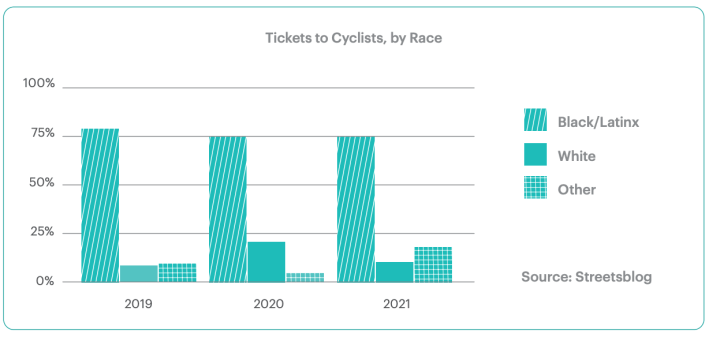

Studies show that that Black and Latinx cyclists die in car crashes 3.4 and 1.7 times more often per mile than their White counterparts, in part because communities of color are among the least likely to have access to safe cycling infrastructure in their neighborhoods. Cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City and Tampa, meanwhile, have all found that these demographics are most likely to be the target of police stops for crimes like riding on sidewalks next to fast, dangerous roads without bike lanes. And when those stops happen, they are significantly more likely to turn violent.

"We need to be concerned about the safety and mobility of all people, but for Black people specifically, even with these laws in place, mobility has not been safe for us," said Charles T. Brown, founder and CEO of the nonprofit Equitable Cities and an advisor on the report. "Almost without exception, almost every place that has released this data has shown that Black and brown people are disproportionately targeted. That clearly signals the existence of structural racism within these departments."

Many cities, though, have struggled to address patterns of inequitable enforcement, because they don't collect enough data on either cycling stops or the factors that contribute to cycling crashes. And while the researchers say that policymakers should fill those data gaps, they also shouldn't wait to strike down harmful bike laws that they already know can discourage people from riding and provide a pretext for cops to harass vulnerable groups, particularly the unhoused.

"We have data from the people who have been victimized, but somehow that isn’t seen as credible as the data that’s provided solely by police," Brown added. "Why don’t we trust qualitative data from people harassed by law enforcement? Because we already have that — we just don’t respect it. "

Here are three ways city bike policies are failing riders – and why NACTO says they need to change.

1. Requiring safety equipment instead of requiring safe streets

There's no doubt that helmets, pedestrian-alerting bike bells, and bike lights can help save lives — but laws that punish people for not having them certainly don't, and can quickly transform into an all-too-convenient pretext to criminalize the poor.

Policymakers in Seattle, for instance, recently repealed the city's mandatory helmet law after an analysis revealed that nearly half of citations were issued to unhoused people, many of whom can't afford common bicycle accessories or struggle to store them securely. Black and indigenous people on bikes were also found to be two to four times more likely to be cited for not wearing a helmet than their White counterparts.

Other equipment laws, like Kansas City's now-repealed regulation that allowed officers to cite riders with mud on their wheels for getting the streets dirty, don't even pretend to be about safety, while anti-theft laws, like required "bicycle registrations," almost never result in riders getting stolen bikes back — but do result in violent encounters with cops. Put it all together, and experts say equipment laws can scare marginalized people off riding altogether, which endangers the ones who still do even more.

"Our goal, ultimately, is to enable safer, more connected, and sustainable cities," said Jenny O'Connell, senior program manager at NACTO and the primary author of the report. "If people are discouraged from biking by these laws, that’s a broken system."

2. Regulating rider behaviors rather than keeping people from getting hurt when they make mistakes

Bikes are fundamentally different than cars — but that hasn't stopped U.S. cities from criminalizing people piloting 25 pounds of steel for breaking laws designed with 4,000 pound cars in mind.

Communities across America, for instance, have outlawed the so-called "Idaho" stop, which allows cyclists to simply yield at "stop" signals when they've slowed down and made completely sure the way is clear. The maneuver, which cycling safety experts say can make a person on a bike more visible to the cars behind them, recently became legal in nine states, but is still illegal almost everywhere else, even though researchers say it helps prevent crashes and keep traffic moving when cyclists aren't heavy enough to trigger a weight-actuated stoplight.

Much like equipment laws, "behavior" laws like these have a long history of being used pretextually against people of color. In 2020, for instance, bicyclist Dijon Kizzee was shot and killed by Los Angeles County Sheriff's deputies who said they thought he had reached for a weapon after he fled an initial stop for "splitting traffic" while riding his bike on the wrong side of road, though some said their accounts were untrue.

Even "behavior" stops that don't result in a death, O'Connell says, can have severe consequences for the safety bicyclists — in more ways than one.

"If the most important thing for you, as an advocate, is to keep people safe on your streets, and your city has laws that result in people being entering into cycle of fines and fees, being harassed, or even being killed, that is definitely within the realm of 'transportation safety,'" added O'Connell. "We can't support laws that are resulting in harm, especially if they're not proven to save lives."

3. Policing where people ride rather than just giving them their own lane

Protecting people on sidewalks, on pedestrian plazas, or anywhere else people walk might seem like a good reason to keep a restrictive bike law on the books. But even "location" laws, as NACTO calls them, can actually make streets more dangerous by distracting from the root problem: that bikes have nowhere else that's safe to ride.

A recent study found, for instance, that cyclists who rode on bike lanes next to busy arterials received 75 percent fewer tickets than ones forced to ride on high-volume roads without protected infrastructure. NACTO says that's because "the frequency of location-based violations is almost always an indication that existing bike, and pedestrian, infrastructure is insufficient, inadequate, or non-existent, and that infrastructure improvements, not enforcement, will be a more effective solution."

The researchers were careful to add, though, that adding infrastructure isn't a cure-all to end police harassment of BIPOC — even if it's a necessary first step to stop the violence.

"Black, brown, low-income, and unhoused people are discriminated against disproportionately regardless of the nature of the built environment — in places where you have safe accessible infrastructure, and in places where we don’t have it," Brown noted. "Their skin color, their social status, is really what’s being policed, not the fact that they walked outside of a crosswalk, or that they biked on a sidewalk, or they stepped off a curb at the wrong place....You still want safe infrastructure, though, because we don’t want to give law enforcement a legally justified right to discriminate disproportionately, and right now that’s what they have."

To make streets truly safe for cyclists, experts say reforming the way we enforce bike laws — sometimes including those laws' outright elimination — must be only the first step.

"The framework of 'arrested mobility' demands that we look not just at law enforcement, but at enforcement that happens as a result of policy, planning, and the self-deputization of White citizens," Brown said. "Until we treat the disease of arrested mobility, Black Americans will have neither freedom nor safety on our roadways."