It's an excuse every active transportation activist has heard a million times: "We're not Copenhagen, so we can't make it easier to walk or bike." A new study argues, though, that U.S. cities could aspire to be more like Hoboken, or Osaka, or any number of other overlooked global models of active transportation excellence — and if they did, biking and walking could become an astonishingly powerful tool to confront climate change around the world.

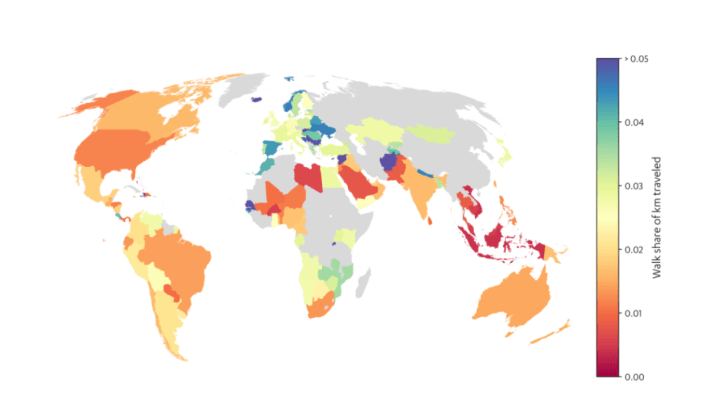

A team of UCLA-based researchers recently took on the daunting task of quantifying "the untapped potential of street redesigns and urban densification to increase walking and cycling" — and putting hard numbers behind how much the planet would benefit if more global cities embraced active modes.

And those numbers were impressive. If every community in the study's sample of 11,587 cities in 121 countries around the world were to outfit the same proportion of their streets with bike lanes as cycling-crazy Copenhagen, the researchers found that global emissions from motor vehicles would plunge by nearly 6 percent — and that's without other car-cutting interventions, like congestion pricing, gas tax increases, or land-use reforms to put more key destinations within walking and biking distance of more homes.

"We often think about walking in biking and related modes being planned locally, which absolutely is the case — but the benefits could be global if we scale them up," said Adam Millard-Ball, the lead author of the paper. "[We need to be] thinking about not just what each individual city would do, but what it would mean for the climate and other aggregate impacts if there was a widespread move towards better walking and biking infrastructure."

Without those sort of insights, though, the researchers say too many climate advocates fail to understand just what a powerful tool they're leaving on the table when they fail to prioritize active transportation — and put too much trust in automakers to tackle the problem alone.

"Global climate modelers have a hard time incorporating policies like street design and bike lanes [into their estimates] because they're implemented by thousands of individual local governments, rather than the nation-state, which is a normally the unit of analysis," Millard-Ball added. "So as a result, a lot of the global climate policy discourse focuses more on technology in the transportation sector, like electrification and fuel efficiency. And certainly that's really important — but it doesn't capture the public transit, [or] the walking and biking policies."

Even when transportation leaders do understand the importance of mode shift to literally saving the human species, the researchers say many believe that "copenhagenizing" their streets isn't possible — and so they barely try to encourage active modes at all, even as other cities whose example they could follow fly under the radar.

"Copenhagen is great, but it's not a place that every city can relate to," he added. "And some mayors may just roll their eyes if you tell them to go and become like Copenhagen. So we wanted to find some success stories in a data-driven way — and not just the usual suspects."

The most slept-on cycling and walking cities

To find those diamonds in the rough, the UCLA team also analyzed which cities in their sample had unusually high levels of biking and walking relative to the rest, as well as relative to other cities in their respective countries, among other factors.

That analysis did generate a few darlings among U.S. urbanists, like daylighting-happy Hoboken, "ultra-low emission" London, and bike lane-rich Montreal — but also some overlooked gems with under-discussed strategies worth stealing. And they were located in a bogglingly wide range of social, political, and cultural contexts, so virtually any community could identify peers to snatch ideas from.

"These aren't just places where urban planners like to go on vacation and take photos of bike lanes, which is often the places that have a good marketing department," Millard-Ball added.

Buenos Aires, for instance, landed on the list in part for its unique focus on expanding sidewalks and low-cost intersection treatments to give walkers more space with little more than paint and planters, in addition to building more traditional protected bike lanes.

Konstanz, Germany, meanwhile, launched an enviable bikeshare scheme featuring cargo bikes to meet a range of traveling needs, as well as implementing "Fahrradstraßen," or bicycle streets, to give priority to cyclists and restrict car use. The city also conducted regular audits of footpaths to make sure they're accessible to people of all ages and abilities.

European cities are often circumscribed with a "ring road," but Leiden, Netherlands, has bounded its with a ring park called the "Singelpark," connecting neighborhoods throughout the community via a single, low-stress route. That effort is complemented by the "Agenda Autoluwe Binnenstad," or low-car city agenda, which aims to put people first as soon as they step within that ring by putting parking lots at the edge of the zone and encouraging drivers to abandon their cars and take public transit instead.

Some of the highest-performing cycling cities didn't even lead with Copenhagen-style bike lanes — and still managed to get a lot of residents in the saddle.

Like many Japanese cities, Osaka has historically skipped even basic infrastructure like raised sidewalks in favor of slow-speed shared streets where walking and cycling zones are demarcated only by a painted line. Now, though, the city is building truly separated cycling paths, aiming to put one every half-kilometer on major roads, while still maintaining its quintessentially Japanese approach to putting people first on almost every street.

In their case studies, the researchers revealed that some of the less-obscure active transportation standouts still had less-talked-about lessons to share with their peers.

Montreal, for instance, got a nod for its uniquely effective community engagement strategies that have helped even hesitant residents and business owners embrace bike lanes and other people-first infrastructure. The city's pedestrian streets are so popular that the French-Canadian city actually has three different versions: pedestrian-only spaces, slow streets that share space with non-motorized bikes, and "woonerf"-style shared streets that allow cars, but also give walkers access to every inch of the road.

London, meanwhile, got a shout out for the unique governance structure that's powered its well-publicized active transportation revolution, using a single strategic transport authority and a mayor-appointed "walking and cycling commissioner" to take ownership of the city's mobility future and foster collaborations with local boroughs and advocacy groups. The Big Smoke has also put forward aggressive planning frameworks, design standards, and tools to encourage non-automotive modes that other cities could copy and adjust to their unique needs.

Even some still-developing nations got some love.

Nairobi made the list in part because it spends more than 30 percent of its transportation funding to non-motorized transit, over and above an official commitment to devote at least 20 percent of funds to people outside cars. It's also working fast to develop a master plan to support those modes and bring down the country's notoriously high pedestrian fatality rate, which could serve as a model for other global cities struggling to confront traffic violence without the significant resources of the Global North.

The sheer breadth of cultures, climates, and contexts in which active transportation is thriving prove that any city on Earth can become a haven for people outside cars, Milard-Ball said — if they do the work to find and imitate the model cities that are most relevant to them.

Throughout their sample, the researchers found that environmental factors like ultra-hot or ultra-cold weather actually didn't predict whether a city would choose non-automotive travel at high rates, and even steep terrain didn't keep scare people off of walking (though it did minimize biking — at least while hill-killing e-bikes remain in the minority). And national-scale challenges like artificially low gas prices and limited rail service did soften a city's cycling and walking numbers, but they weren't impossible to overcome.

"There's not just one model for good street design," Millard-Ball emphasizes. "Planners can mix and match and take inspiration from different success stories that they think their elected officials and residents can relate to. Whether it's the public engagement strategies of Montreal or the narrow streets of Osaka or the pedestrian spaces of Buenos Aires, there's something there for everyone — and it's not a good enough excuse to say that you 'can't become like Copenhagen.'"