A new bill could slash red tape that’s strangling America's ability to design safe streets for vulnerable road users, by re-thinking the fundamentals of one of our most controversial road design documents.

Last week, Sen. John Fetterman (D–Penn.) quietly introduced the Building Safer Streets Act, which would require the Federal Highway Administration and US DOT to institute a slate of reforms aimed at building safer roadway infrastructure, while ensuring that small communities can access the federal funds they need to make those changes.

Finally, a senator talking about removing barriers put up by @USDOTFHWA @USDOT to designing and building truly safe roads. Thank you @SenFettermanPA! And how about the incredible job by @walk_left explaining hose barriers and the need for change! https://t.co/WDjwC95ChH

— Beth Osborne (@BethOsborneT4A) November 9, 2023

There’s a lot packed into the slim bill’s seven pages, including changes to the Safe Streets and Roads for All program which would guarantee that 10 percent of funds are set aside for communities under 250,000 residents. It would also finally close the loophole that allows roughly one-third of states to keep their federal safety funding if they set roadway fatality “targets” higher than the number of deaths they recorded in previous years, and prevent the Federal Highway Administration from giving states points on grant applications for projects that raise speed limits on non-freeway roads.

The bulk of the legislation, though, gets deep into the weeds of the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices, a once-obscure 800+ page manual whose revision prompted a flood of 25,000 comments from safe streets advocates concerned that its upcoming revision wouldn’t adequately center the needs of people outside cars. And with pedestrian deaths already setting records, Fetterman says those changes are long overdue.

“The bottom line is that we are facing a street safety crisis in America — and in Pennsylvania. The thousands of lives we lose due to unsafe streets is unacceptable, and it’s long past time we in Washington do something about it,” Fetterman said in a statement. “I’m proud to introduce this bill to provide communities—especially our smaller towns—with the resources and guidance they need to make their streets safer.”

How the MUTCD Makes Roads More Dangerous

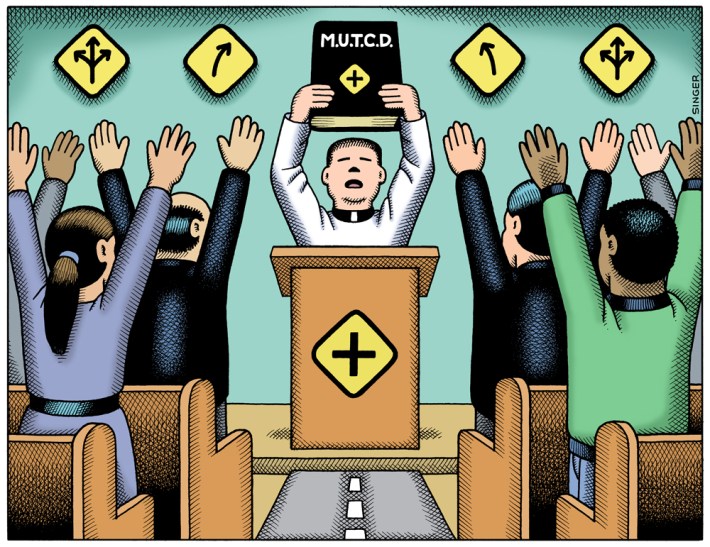

Once called a “recipe book for the roads” by walkability expert and former Streetsblog USA Editor Angie Schmitt, the MUTCD — which is published every four years by the Federal Highway Administration — has long occupied a powerful but poorly understood place in the traffic engineering profession, which looks to its standards to decide how to design the signs, signals and markings that communicate the rules of the road.

Many of those standards are pretty benign, like the rule that a green light should mean “go” everywhere in America, or that a stop sign should be shaped like an octagon rather than a square. Others, though, have far more dire implications, up to and including who lives and dies on U.S. streets. The Manual’s infamous “85th-percentile rule,” for instance, recommends that the number that appears on speed limits signs be set within five miles of per hour of the speeds that 85 percent of drivers naturally travel when no one else is on the road — even if those velocities are lethal for pedestrians, and despite the fact that the standard was created for two-lane rural highways and is widely considered unsafe in urban contexts.

A new version of the Manual proposed in 2021 — which was rumored to be written with an eye towards making streets more legible to the limited computer vision of autonomous vehicles, rather than enhancing pedestrian safety — would have made other problematic recommendations, too.

One version advised against safe bike lane intersection treatments that are common across U.S. cities, a move that the National Association of City Transportation Officials warned would amount to a “poison pill” for the thousands of cities whose infrastructure would instantly become non-compliant. Other provisions discouraged the use of colorful crosswalks, despite the fact that studies show they can actually slash vulnerable road user crashes by 50 percent compared to the all-white designs the Manual recommends.

And when cities want to use those life-saving design elements anyway, they’re often scared off of doing it, lest they fall out of compliance with the all-powerful Manual — even though, technically, not all of its recommendations are legally binding, much like its companion document, the AASHTO Green Book. In part because remaining in compliance with the MUTCD may shield transportation agencies against lawsuits, many traffic engineers tend to treat it more like a Bible with strict commandments than a “recipe book” that encourages chefs to sub out the nuts if they’ll send the person who’ll actually eat the dish into anaphylactic shock.

And the FHWA and other government agencies, in turn, often require engineers to conduct costly studies to prove that deploying safe road designs is worth granting an exception to those restrictive federal standards — even if piles of research have verified that those designs save lives, and that the standards in the Manual don’t.

“There have been times in the past when the feds would send a letter to a city that was doing something like building a rainbow crosswalk, and they’d say, ‘This is not in compliance with the MUTCD,’” added Alex Engel, senior manager of communications for NACTO. “And cities would be a little spooked by that, because the feds control a lot of funding. There’s also the liability concern; if someone does get hit at intersection [with a rainbow crosswalk], would a court or a jury find the city liable for it because it's not up to specification to the MUTCD? Because whether or not [those regulations against rainbow crosswalks are] actually sensical doesn't matter as much as whether or not they might win.”

How Fetterman's Bill Could Help

As the FHWA continues revising the Manual — the redux is expected to be published later this year — the Building Safe Streets Act would require the agency to take several actions to bring that troubling tome into the 21st century, with most measures required to be completed within a year or two of each new version.

First, the Manual’s authors would have to show their homework when safe design elements are outlawed, including any research that supports the rule, proof that it actually complies with federal law, and a list of when cities can exercise their judgment and use them anyway.

Second, it would require many common multimodal infrastructure elements to be listed as “categorical design exceptions” from the standards in certain contexts — including federal Proven Safety Countermeasures that were rubber-stamped by DOT years ago but still aren’t always allowed under the MUTCD — and streamline the process for requesting exemptions that allow for other life-saving changes.

Third, it would require transportation officials to write new guidelines for building multimodal streets that reflects the unique context of each road, including whether it’s located in urban, suburban or rural area, whether it’s a freight corridor, and how to best incorporate transit stops.

Finally, it would ask the Government Accountability Office to conduct a study on how transportation professionals actually use the MUTCD, to give a better sense of how often — if ever — they’re exercising the engineering discretion the Manual affords them now, and how much money and time they spend to prove that their exceptions are worth the perceived legal risk.

Of course, none of those changes really needs the force of a Congressional mandate to pass — and Engel doesn’t really expect that the current congress will grant it. Still, he hopes that by shining a light on the structural reasons why something as simple as a good bike lane is so hard to find on U.S. roads, federal transportation officials will finally take action to correct them.

“For the most part, it’s just mandating the agencies move faster than they currently are, and be a bit more holistic [as they] look through their current regulations,” Engel added. “[They need to] update them to work for everyone.”