In a move that could be a model for other U.S. states, Oregon may soon allow cities more leeway to set lower speed limits on dangerous roads — rather than reserving that power for state transportation leaders whose primary interest, historically, has been moving cars as quickly as possible.

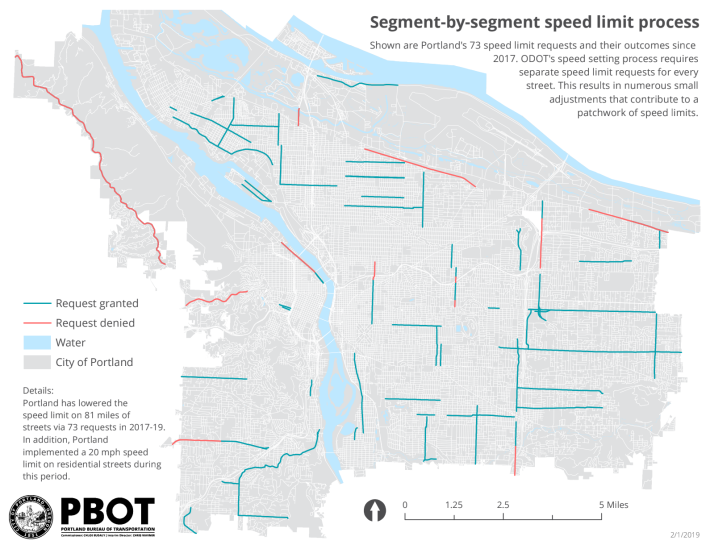

Following an exhausting 13-year battle, the Beaver State legislature recently modified a law that required cities and counties to individually lobby the Oregon Department of Transportation every time they wanted to lower a speed limit in their communities, essentially giving non-local transportation leaders final say over how fast drivers should travel in places they don't live.

As part of that onerous process, locals would have to wait between six and 12 months to find out whether their safety would come first — and often, their requests were denied.

"We started bumping up against situations where the public would want these changes, and we would have to educate them about the fact that this issue is not entirely within our control," said Dylan Rivera, a spokesperson for the Portland Bureau of Transportation, which spearheaded the campaign for the reform. "This is a long time coming."

Portland's plight isn't uncommon among U.S. cities; Portland Bureau of Transportation reps say apart from a tiny handful of states like Virginia, they had few national models when the fight for local control over their speed limits began.

And much like communities in those states, Oregon cities still won't have control over every limit, including those that are governed by state law — think the 65 mile per hour max on the interstate, or 20 miles per hour when children are present in school zones — and on state-controlled roads within city borders. And even on local roads, speed-setting authority won't be given by right; cities will have to apply for it, and prove that they have enough engineers on staff to provide meaningful speed recommendations, which could be a stumbling block for smaller rural communities.

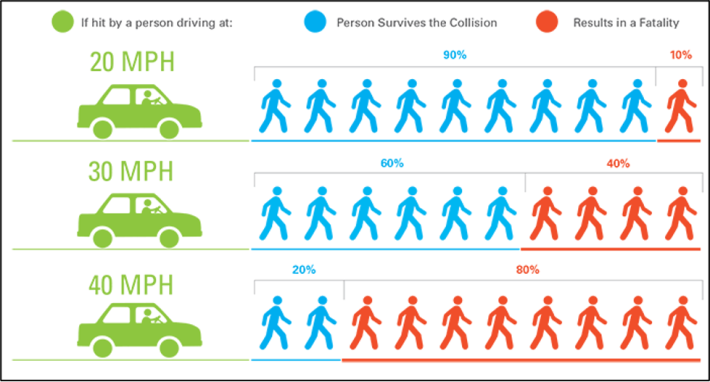

To help address those concerns, the Bureau of Transportation launched a parallel campaign to get the state to ditch the infamous "85th percentile rule" in the speed limit assessments that will remain under its control. Rather than setting limits based on the what's actually safe for all road users who might travel on a given corridor, U.S. traffic engineers are generally advised to measure the average speeds at which most motorists — specifically, all but the fastest 15 percent — decide they can safely travel, averaged over 24 hours worth of data that includes the middle of the night when roads are wide open and driving fast is the norm.

Now, many Oregon roads will be subject to a significantly safer 50th percentile rule, wherein the slowest half of drivers on the road will set the standard. State engineers will also have to consider the lived realities of those roads, including what businesses, services and residences are located along them, how they're classified locally, and other more complex factors.

"We said to ourselves, 'Well, they could delegate authority to us, but if we have to set speed limits with the same paradigm that ODOT had used authority, that wouldn’t necessarily achieve the safety improvements we were seeking,'" said Dana Dickman, safety section manager for PBOT. "These changes in methodology will allow us, as an agency, to have a deeper conversation about their state-owned roads that run through our city."

Even those deep conversations, though, are only the next step in the longer journey towards taming every dangerous road in every Oregon city.

Getting from a safe speed limit on a sign to a comprehensively design speed across an entire roadway environment, Rivera says, will sometimes require cities actually taking ownership of the dangerous corridors that ODOT maintains — as PBOT recently did on deadly 82nd avenue — not to mention finding the money to transform them into human-scaled places.

"What we’ve found is that transferring ownership of a state highway to a city doesn’t in and of itself provide safety improvements," added Rivera. "What does that is the change in ownership plus the resources to make those improvements happen ... We need money to address deferred maintenance, to mark crosswalks where they haven’t existed and they’re overdue."

Rivera is clear, though, that Portland isn't shying away from the sometimes complex challenges of slowing down drivers citywide, because it's essential to achieving the City of Roses' ambitious goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2025. As part of a separate effort, the city already won the right to slow to 20 miles per hour in 2018, and it's continuing to redesign its roads to reinforce those limits as fast as possible.

If and when Portland's application for local speed limit authority is approved, which Rivera is hopeful it will, that will give the city one more tool to save lives — and other states may want to consider adding it to their toolboxes, too.

"We think local control is really critical to helping us address the transportation safety needs of our community, given the needs of an urban enviroinment and how different they are from more rural and other environments," Rivera added. "That authority, plus the ability to embrace a new paradigm that focuses on saving lives as the outcome — it's critical to us achieving our goal of Vision Zero."