America's sprawl problem is worse than many advocates assume, a new study finds — and if left unaddressed, it will have increasingly dire consequences as the global climate emergency accelerates.

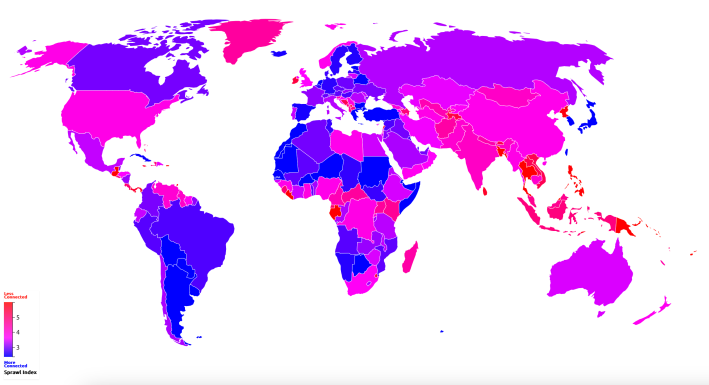

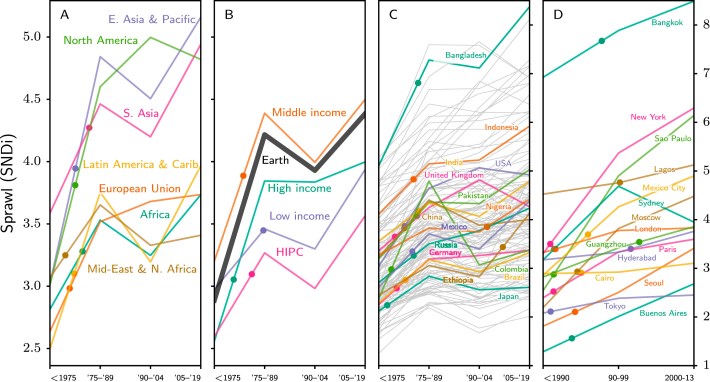

A team of researchers recently took on the daunting task of analyzing and scoring the "sprawl index score" of every country on Earth, as well as how sprawl makes it harder — or easier — for residents to access direct routes to the destinations they rely on, particularly when traveling on sustainable modes.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the sheer prevalence of things like gated communities, cul-de-sacs, unnecessarily curvy roads, and other street grid features that force travelers to go way out of their way ended up ranking the U.S. among the least-connected nations in the global north, rivaled only by mountainous countries like Norway and relatively car-dominated nations like Ireland.

Places like Japan and Argentina, meanwhile, ranked among the most-connected countries on the planet, even if previous sprawl studies didn't recognize them as standouts. The researchers explained that while those nations' non-gridded street patterns don't closely resemble connected communities in North America, they still offer ample cut-throughs for people outside cars, and other innovative strategies to shorten traveling distances.

Even though connected cities are undoubtedly more convenient, many Americans will happily pay a premium to live in disconnected neighborhoods, whether they're lured by the promise of privacy, quiet, hillside views, or isolation from what some residents might (troublingly) view as "undesirable" neighbors nearby. At the community scale, though, increasing sprawl has a wide range of harmful effects, including increased driving emissions, car crashes, and a raft of negative public health outcomes associated with a culture where most have no choice but to get behind the wheel.

“[Sprawl] really locks in car dependence," said urban planning professor Adam Millard-Ball, director of the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies and the lead author of the paper. "And once it's built, it's really hard to provide transit service to a neighborhood where the streets aren't connected. … Even what you might think would be simple things, like cutting a path to link up cul-de-sacs, can be physically challenging, but also politically [challenging]. Because people bought a house on the expectation that no one be walking through [their yard].”

One of the most devastating downsides of sprawl, of course, is how it can compound the impacts of a climate disaster — something Millard-Ball, who is based in Los Angeles, has witnessed firsthand during this month's deadly firestorms. The wealthy hillside canyon neighborhoods that were among those most devastated by the Palisades fire were also among the least-connected regions in the Los Angeles area, in part because many of them offer only a handful of exits to a main highway; some residents fleeing that fire were even forced to abandon their cars when a chokepoints became too overwhelmed with traffic to allow most to pass through.

Of course, street connectivity certainly is far from the only factor that shapes the impact of a disaster; Millard-Ball notes the mixed-income Altadena area that was devastated by the Eaton fire is among the most-connected L.A. neighborhoods, and many of the downtown neighborhoods devastated by Hurricane Helene in Asheville were home to a highly connected grid, too. Still, he says the role of sprawl during climate emergencies still deserves discussion, especially when it enables moneyed developers to cultivate what Guardian architecture critic Oliver Wainwright recently called a "pyrophilic urban form" in fire-prone natural environments, or other regions where disasters are likely to be especially devastating.

“I don't want any of this to come across as blaming people for living in a particular neighborhood," Millard-Ball added. "The evacuations and the fire came so suddenly; it was, and still is, an incredibly traumatic situation. … But one thing you can say is that a lack of connectivity is an added risk factor. All else being equal, if there's only one road out, then that community is likely to be a greater risk.”

Millard-Ball acknowledged that once a sprawling street network is in the ground, it's likely there to stay — which is why it's imperative that states address street connectivity before they permit any new development, and allow developers to increase density in already-connected regions.

“Buildings come and go and [they] adapt over the years … but streets are really hard to change," he added. "Thinking back over the human history, even after incredible devastation, people tend to rebuild exactly the way the streets were before. … The decisions we [make about] the pattern of streets have really long-term implications for car dependence, and [can] basically transit-proof or pedestrian-proof a development.”

Even the most-sprawling neighborhoods, though, can be retrofitted, at least if decision makers and residents are willing to be bold and get creative. It might not always be easy to tackle the biggest contributors to sprawl like downtown highways — which Millard-Ball calls a "huge, self-inflicted barrier to pedestrian movement" — but it is possible to cap or even remove them. And smaller tweaks at the neighborhood level are possible, too.

"There are opportunities, on a case-by-case basis, to say, ‘Hey, is this a place where we can connect adjacent cul-de-sacs for people on not, but leave it a cup-de-sac for cars?’" he added. "Or, ‘Is this a place where we don't need a wall [between this [neighborhood] and the Trader Joe's? Maybe we can have more gates onto the arterial for pedestrians, to provide more direct routes?”

By looking to international examples and thinking outside the box, America can confront what might feel like baked-in sprawl patterns before the next climate disaster hits – and in the process, reduce the emissions that are driving the disasters in the first place. And perhaps the best evidence is that America's "sprawl index score," which the researchers found has actually fallen slightly between 2004 and today.

“Streets are really the skeleton that allows more sustainable cities to emerge," Millard-Ball said. "Having a connected street network doesn't guarantee that you'll have walkable transit-oriented communities — but if the community decides to go that way, it makes it much easier for it to happen.”