Earlier this year, an Orlando woman and a group of teenage accomplices — reportedly wielding a jackhammer, a set of bolt cutters, a sledge hammer— went viral for repeatedly tearing down chain link fences that blocked pedestrian and vehicle traffic into their neighborhood, all while a sheriff's deputy looked on and did nothing.

That’s because the headline-grabbing moment wasn’t actually an act of vandalism at all — and for the woman at the center of the story, then 39-year old Delila Smalley, it was an important act of spatial justice.

Smalley, who’s lived on the Agnes Heights subdivision side of the fence for 12 years, says it was actually her teenage son and nephew who tore initially tore down the barrier. She quickly joined their cause, though, because she'd grown tired of watching children from the income-restricted apartment complex on the other side injure themselves while attempting to climb it. She says some of those injuries had been so bad that children ended up in the hospital; others had their clothes ruined when they snagged on the wire, or when neighbors put paint along the tops of the fences to catch “trespassers” in the act.

Even the possibility of a bad fall or a ruined outfit their families couldn’t afford to replace, though, still seemingly felt safer to these children than braving the longer and far more dangerous walk along five-lane, 35-mile-per-hour Curry Ford Road to the north — because with Agnes Heights closed off, that’s the only other way to access most of the area’s schools, churches, parks, and bus stops.

So I was handed a pretty wild story over the weekend. A woman had a group of teenagers vandalize an Orange County-owned fence IN FRONT OF LAW ENFORCEMENT. No one stopped them!

— Nick Papantonis WFTV (@NPapantonisWFTV) February 20, 2023

At six -- why she did it, and why they didn't step in. @WFTV pic.twitter.com/VEHRs7B1lB

A former schoolteacher herself, Smalley says both she and her son have been struck by drivers before, and she has vivid memories of losing a childhood friend to traffic violence on another dangerous road.

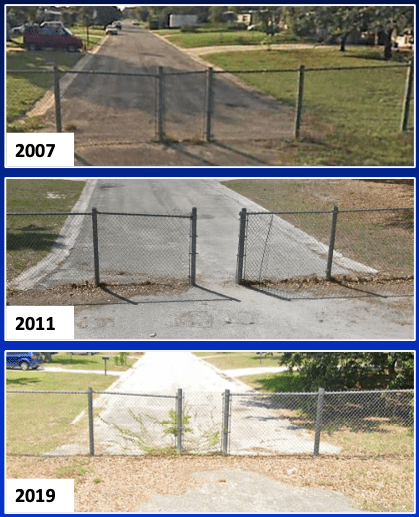

So when she found out that the fences had been built “off the books” by a county commissioner who just happened to live in Agnes Heights in the 1980s and wanted his neighborhood to be quieter — and that those fences had been unofficially opened and closed to pedestrians by residents at various intervals ever since — Smalley saw no good reason they should stay standing.

“Some people on my side of the fence think it’s their private right to have this road blocked off from children who aren’t bothering anyone,” she added. “I just couldn’t disagree more. …They call it a ‘safety fence.’ I call it a ‘segregation fence.’ And they have no right to segregate our community.”

‘The fence was there for a reason’

Smalley’s government, though, may or may not be on board with her plan, even as many of her neighbors signal their support.

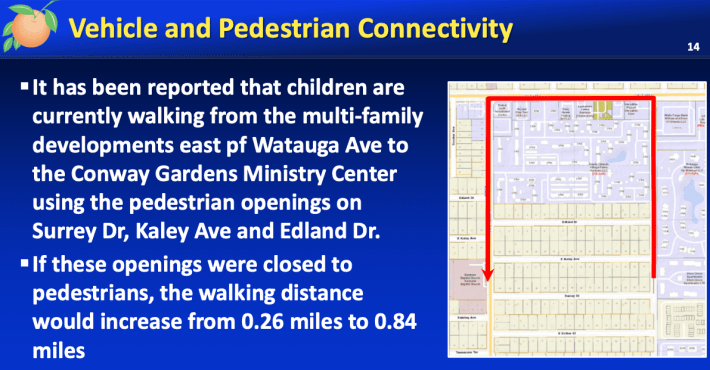

In the months since her and the teenagers’ unconventional act of tactical urbanism, the Orange County Public Works Department has launched a formal process to decide what should be done about the barriers, including completing the demolition process Smalley and the teenagers started, restoring the fence but restoring pedestrian cut-throughs, or building a brick wall for which surrounding residents would have to pay an estimated $100,000. (Bafflingly, an option to restore the fence as it was without pedestrian openings also seems to be on the table, despite the fact that the agency says it doesn’t comply with the city’s comprehensive plan.)

The county has indicated that the board of comissioners intend to make a decision before the end of November.

One of Smalley’s neighbors, meanwhile, has launched his own petition urging the county to build an eight foot steel wall (which transportation officials have said they will not do) and alleged that Smalley was the one sowing division by tearing down the divider, and opening their community to “vandalism, home intrusions, car break-ins and gunshot violence.”

“Creating hatred among the community is intolerable,” wrote resident Allan MacDonald on Change.org. “If a person climbs fencing and get hurt, the fence was there for a reason. … We do not need to remove the obstacle, we need to educate people. Home values will plummet, and crime will open up a new chapter into our lives.”

An October presentation from the department of public works, though, found that “no significant increases in crime [had] been reported since [the] removal of the fencing on Watauga Ave.” Information on home values was not immediately available.

Who is infrastructure for?

Smalley’s story may be full of theatrical details — she confirms that she used a jackhammer, a sledge hammer, and a bolt cutter to tear down the fence, but says a metal angle grinder was what “proved to be the most effective,” and she denies reports that she wore a cat burglar-style ski mask while she completed her work. But some advocates say her story echoes a broader national conversation about how pedestrian access is shaped in the U.S., and who really gets a say in the process.

One of them was Thomas DeVito, national director of the nonprofit Families for Safe Streets, whose group Smalley approached for support in the lead up to county’s decision. He was moved by her story, and saw it as a “microcosm of broader trends” in the “selective privatization of key parts of the public realm, to the detriment of the wider ecosystem of public goods.”

"Transportation policy decisions have long been used to reinforce unjust and inequitable social outcomes," said DeVito. "It’s reflected by the disproportionate leveling of low-income neighborhoods across the U.S. to build urban freeways, the lack of convenient and safe crossings on some of our most dangerous stroads, the dearth of sidewalks in many of our suburban and exurban communities, and the decades-long divestment in transit options serving cities and towns across the United States. The message is simple: if the infrastructure or policy doesn’t serve the wealthiest and most comfortable first, it’s on thin ice.”

Despite echoes of those headline-making policy failures, though, Smalley’s story is also an example of the quieter ways that pedestrians are losing ground in American cities — at the hands of their neighbors as much as their governments. And while few of those neighbors just so happen to also be county commissioners with enough political pull to get a fence built off the books, plenty have enough power to, say, privatize a public road and shutter it to all non-resident-traffic, while others can confidently leave their cars parked on the sidewalk with little pushback from police (at least if police themselves aren’t the ones doing it.)

And that’s to say nothing of all the smaller, daily indignities of missing curb ramps and tactile pavers required under the ADA, unshoveled walkways in non-Floridian winters, overgrown street verges, sprinklers aimed squarely at pedestrians, and on and on and on. Notably, even if Smalley succeeds in her quest to make pedestrian access to her neighborhood permanent, Agnes Heights still does not have continuous sidewalks, because the city of Orlando doesn't require the neighborhood to build them, and has not taken on that responsibility itself.

Even without sidewalks, though, many Floridians still believe that Agnes Heights should open itself up to walkers — at least as a first step towards better accessibility and connectivity.

Lauren Torres — who lived in one of the apartment complexes along Watauga Avenue herself, and today serves as a board member for Bike/Walk Central Florida — points out that at various points in their history, the barriers actually did have pedestrian openings, before neighbors took it upon themselves to close them up again.

“That’s the route my brother and sister would take to get to school,” Torres added. “Leaving at least a small pedestrian space open is the least that we can do. People drive 45 miles per hour on Curry Ford Road; having those kids walk there, when there’s an easier [route] right in their community — it just isn’t a good idea.”

The future

For Smalley, the fight to keep Agnes Heights open to walkers didn’t end the last time she jack-hammered the fences out of the ground. In true Florida fashion, she’s been rollerblading to visit the barriers daily to ensure her neighbors didn’t put them back up, as well as acting as an “informal crossing guard” for area children and rallying her neighbors to speak up about the importance of opening their community to their neighbors. She says she’d be comfortable with restricting car access to the area, but restoring pedestrian and bike access are a must, especially with a neighborhood bikeway proposed along Watauga by 2030.

“At this point, I’m just trying to make sure this walkway stays open and that kids have a safe sidewalk to get to school,” she adds. “I don’t think it should have to get one of these children getting run over for someone to listen.”