It’s generally understood that the construction of America’s highway system took a great toll on our society, but in the Twin Cities, land once set aside for housing, industry and agriculture were the most decimated.

Minnesota provides a perfect window into how communities — mostly African-American ones — were the greatest victims not just by the extent of land lost, but also by the role these places once played.

In the Gopher State, highway construction comprises so many broken promises, starting with the theft of land from the Dakota in 1851 and continuing to the construction of Olson Memorial Highway from the 1930s to the '50s. Those racially motivated atrocities are part of a broader pattern of abuse that includes racial covenants, redlining, biased policing, and violence that has created inequitable urban spaces.

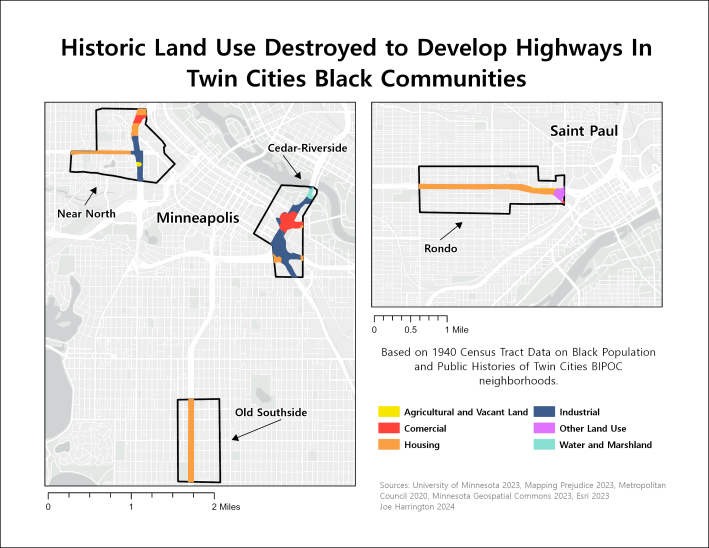

This blueprint was scaled in the 1960s as major highways like I-94, I-35E, and I-35W divided and displaced communities in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

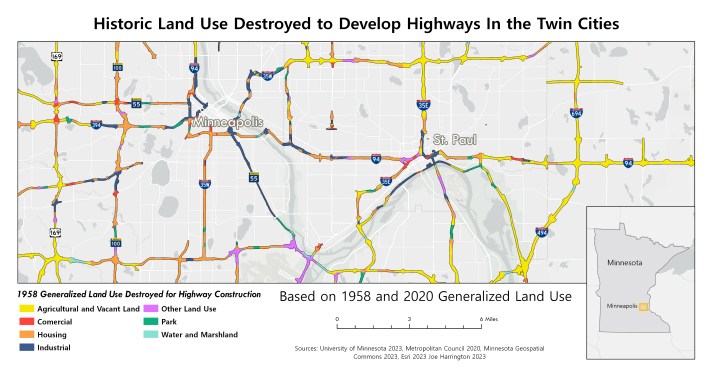

In the vast Twin Cities metropolitan region, nearly 50 square miles of land was converted from a variety of uses to highway infrastructures. That's basically an area the size of Minneapolis.

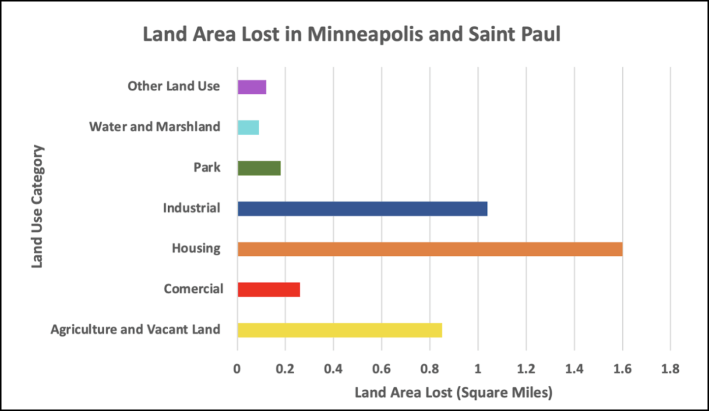

In the downtown cores of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 4.14 square miles of land were consumed by highway construction, a sizable 3.6 percent of the two cities’ combined area. Housing, comprising a mix of single and multi-family homes and apartments, and industrial space were the most affected.

What does that look like?

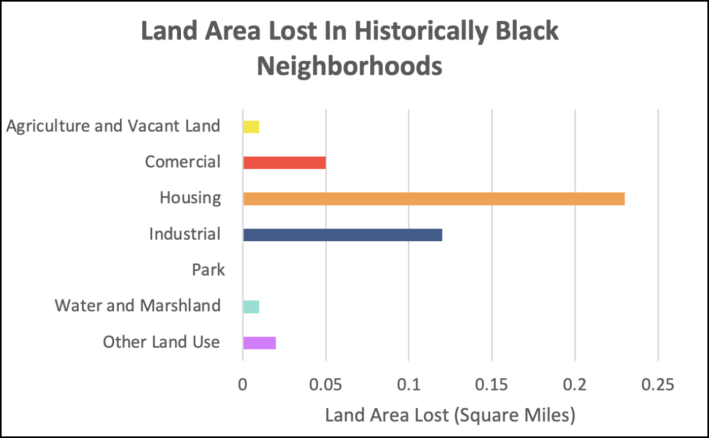

The chart above shows that urban housing was the greatest victim of highway construction in the Twin Cities, but the harm was greatest in the cities’ Black communities of Near North, Cedar-Riverside, and Old Southside in Minneapolis, and Rondo in St. Paul.

These communities accounted for just 2.82 square miles, roughly 2.3 percent of Minneapolis and St. Paul’s combined land area, but highway construction razed 15.6 percent of the land.

Housing, industrial, and commercial land comprised the majority of these losses, stripping communities of homes, jobs, businesses, and community spaces. What was left was divided and disrupted, changing the social landscape of these communities.

Some white residents were displaced by highway construction, but racial covenants, violence, intimidation, and other tactics prevented Black residents from moving freely to other areas of the cities or suburbs. This siloed people of color into neighborhoods along highway corridors and subjected them to ongoing harms today.

Even a small loss of land can have an outsized impact on a community’s collective life, reshaping relationships between the city and its people. Countless restaurants and bars where people could connect and relax were torn down. Places of worship where people gathered to celebrate and mourn were destroyed or relocated. Urban amenities like grocery stores, and healthcare facilities had to close their doors. Even the mundane experiences, like running into your neighbors on the sidewalk or in a park, was changed.

Today, these spaces are still occupied by highways.

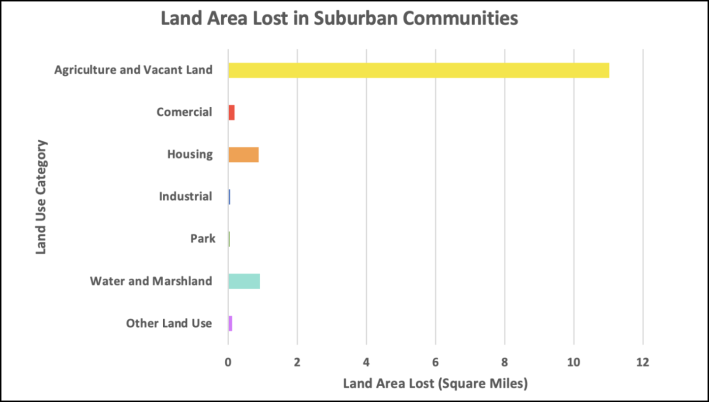

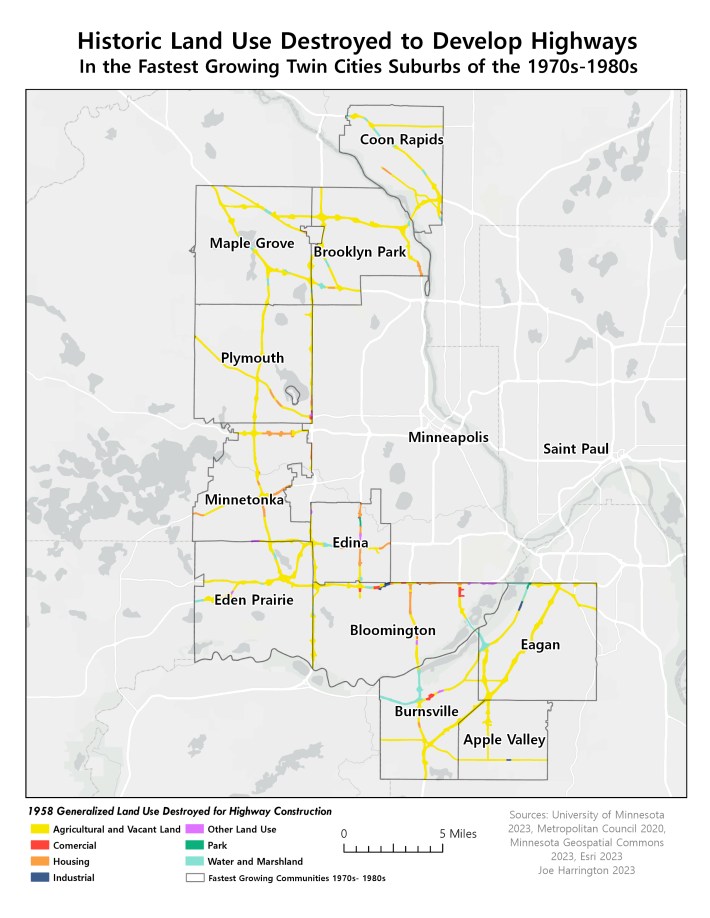

What did the suburbs lose?

In suburban communities, highway construction took a different toll. Agricultural and vacant land was the largest affected land use category, by far. In 11 fast-growing suburban areas during highway construction, highways consumed 13.23 square miles of land, of which 84 percent (or 11.02 square miles) was vacant or agricultural.

In total, these suburban communities lost 4.3 percent of their total land area.

Rapid suburban growth during the freeway era allowed for intentional highway-centric design, benefiting commuters while minimizing disruption and displacement. This contrasted with urban areas, where highway construction caused more displacement in densely developed neighborhoods and aligned with racial and class-based disinvestment policies.

Highway planners and government officials cemented how we use urban space and access employment, goods and services, and other amenities for generations. In the process they created a contested allocation of urban space, raising the question: who are highways – and the spaces they displaced – really for?

Highways were often promoted as community assets, but have instead blighted urbanites and suburbanites, especially African-Americans and low-income residents with environmental, health and economic costs. Cities lost valuable land and tax revenue to state and federal roadways, mirroring nationwide patterns where highway construction destroyed billions in wealth for people of color and millions in potential tax income.

A road map for a better future?

As highways are re-evaluated for the first time since their construction, there is growing awareness about their harms and a once-in-a-generation opportunity to think differently about them. While the cost of these roadways does not outweigh the value of the land they occupy – over $4 trillion nationwide – it will take a fundamental shift in our transportation planning logic and the values that drive it to make gains in equitable transportation and land use.

As we reimagine urban spaces, we must focus on communities that have endured historic and ongoing harm from highways, while recognizing those who have benefited most.

The built environment and policies that shape communities reflect our values. It’s time to bring back spaces of collective life, places to live, places to work, places to relax, and opportunities to build wealth, all stripped from American cities and communities living along highways.

About this Analysis

This analysis uses 2020 generalized land use to establish the existing land area occupied by highways and supporting infrastructures. A 1958 generalized land use map was then used to identify the types and extent of land use lost to highway construction in Minneapolis and St. Paul’s four historically black neighborhoods, the 11 suburban communities that grew the fastest in the two decades following highway construction, and Minneapolis and St. Paul as a whole.