This piece originally appeared on Streets.mn.

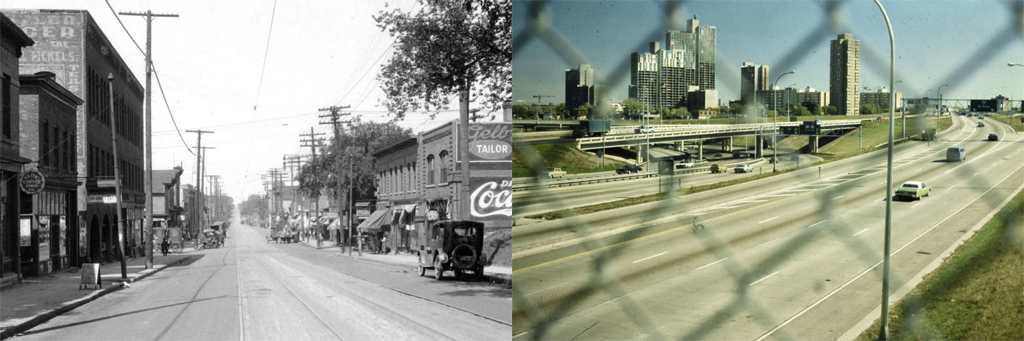

Cities in the United States underwent major surgery between 1940 and 1970 to make way for the construction of the interstate highway system.

In the Twin Cities, highway construction displaced 30,000 residents, many of whom were Black residents living in neighborhoods that planners considered disposable. The highways were also convenient tools to rid the cities of perceived social ills, a mindset deeply embedded in white supremacy.

Today, the legacy of these planning decisions is clear. Communities along highways face intersectional health, environmental, equity and mobility harms. This land no longer serves communities in adjacent neighborhoods with multimodal transportation, community business space and housing, instead prioritizing suburban commuting and car-oriented development.

But maps and data tell only part of the story of the neighborhoods damaged by highways, missing the cultural landscape of Twin Cities neighborhoods, their people, and past and ongoing harms and resistance.

Rich public history work has been done to tell the story of Rondo and Union Park in St. Paul and South Minneapolis along I-35, but the stories of other communities remain hidden from our collective memory. Our Streets Minneapolis has collaborated with the University of Minnesota’s Public History and Heritage Studies Program, the Mapping Prejudice Project, student researchers, neighborhood organizations, and residents to investigate the history and present of life along these concrete rivers. These histories tell the story of Sixth Avenue North, destroyed to construct Olson Memorial Highway (Minnesota State Highway 55) and Cedar-Riverside, partially destroyed and divided to construct I-94.

Sixth Avenue North

The intersection of Olson Memorial Highway and I-94, where you can now hear the roar of traffic through the Harrison Neighborhood and downtown Minneapolis, was once the epicenter of Black and Jewish life in Minneapolis.

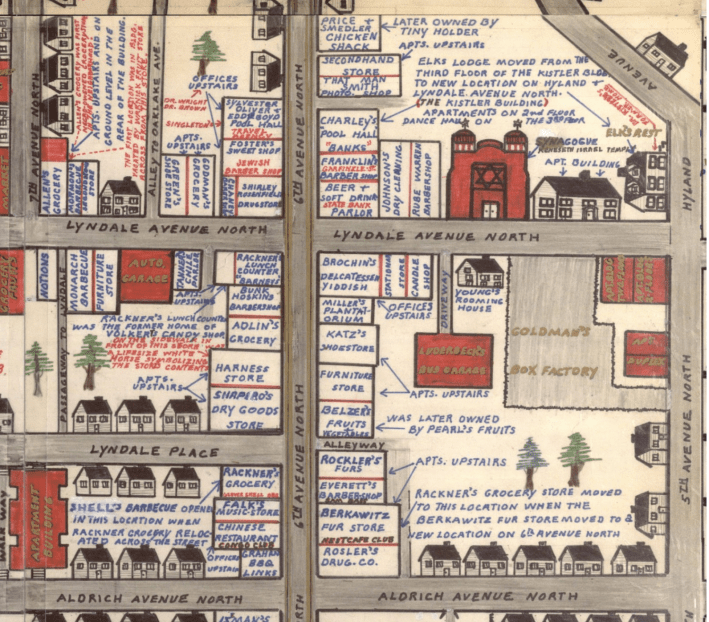

The Corner of Sixth Avenue North and Lyndale Avenue, from a portion of Clarence Miller’s memory map (depicting the neighborhood in the 1920s). Courtesy Hennepin County Libraries.

The Corner, as it was known, at old Sixth Avenue and Lyndale, was packed with small groceries, diners, houses of worship and bars. Jewish delis and grocery stores helped immigrant families escaping pogroms in Eastern Europe, and “black and tan” (mixed race) jazz clubs connected new and touring talent. Nearby was the Black Elk’s club, a movie theater, bathhouses, schools, settlement houses that supported a wealth of youth and adult programming, the NAACP’s favorite ice cream parlor meeting place and Sumner Library (the only remaining building from those days). In the 1930s the houses (built primarily by earlier wealthy settlers in the 1880s) were also poor and run-down, as Black and Jewish residents had harder times finding employment, business and home loans, and improvement funds.

In the 1920s, music and bootlegging both thrived in North Minneapolis as rare employment opportunities for Black and Jewish residents, but morality squads and city planners deplored racial mixing and bar culture. These factors made the area prime cheap real estate for the city’s earliest highway, Olson Memorial, today’s MN 55.

The first phase of construction razed the northern half of the street in the late 1930s and the southern half in the 1950s. In the late 1960s, I-94 would complete the destruction of the corner and affect other North Minneapolis establishments like the Phyllis Wheatley House (a center for the city’s growing Black population) and other neighborhood gathering places. Jewish families had already begun to move to the western suburbs, and remaining residents were concentrated in new public housing developments. Community centers like The Way and Glenwood fostered music talent (and KMOJ radio), and the neighborhood became home to Hmong and Hispanic communities in the 1970s.

Heritage Park replaced Sumner Field public housing, and although it connects many families in the neighborhood, the public-private development project appears to be poorly managed and maintained. The neighborhood is not the walkable, accessible hub that it once was, and the tangle of highways presents hazards to health, pedestrian safety and community connection.

Cedar-Riverside

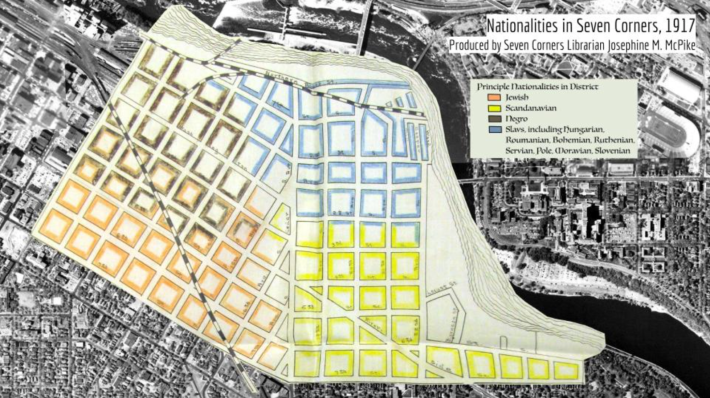

A similar pattern emerged in Cedar-Riverside, southeast of old Sixth Avenue North and downtown, along the Mississippi River. The Seven Corners and Riverside area were the city’s earliest immigrant neighborhoods, where Slavic, Bohemian, Scandinavian, Jewish and other immigrants found labor jobs and housing along the river flats and “uptown” near the many mills, breweries and train tracks.

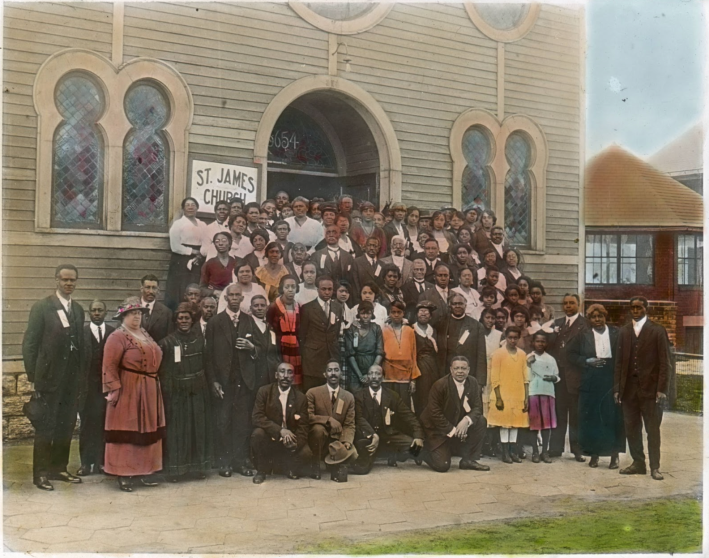

As in North Minneapolis, the lack of racial covenants meant that Black families and immigrant families packed in here. Swedish churches and bakeries, Augsburg Seminary and Trinity Lutheran Church, brewery bars like Palmer’s, the city’s first Black Congregation at St. James AME and Pillsbury United Community’s settlement house, plus three elementary schools and the diverse Seven Corners Library, all supported the dense, vibrant neighborhood. In the 1950s, a Black-owned music club called the Key Club offered employment and entertainment to many Black Minnesotans near Seven Corners, and the Holland Bar was a safe haven for queer clientele.

The neighborhood was massively disrupted beginning in 1957 by the twin displacement efforts of the University of Minnesota’s West Bank expansion and two interstates. Eminent domain meant residents in the path of the West Bank, I-94 and I-35 were forced to sell their homes and move. The population of Cedar-Riverside plummeted, and the area lost its elementary schools, library, several keystone churches and its walkability.

Affordable housing and a welcoming, diverse and fringe-friendly atmosphere means that Cedar-Riverside has remained a haven for decades, as the counterculture epicenter in the 1960s and ’70s (featuring worker-owned cafes, anarchist and student resistance to so-called urban renewal development, folk and rock clubs, leftist theaters and book and record shops), a landing place for refugees from the Vietnam War in the ’70s and from the Somali Civil War in the 1990s, and an ongoing hub for arts, music and mutual aid. But it is cut off from its neighbors and ringed with retaining walls and the fortress of the university, and still lacks public education institutions and libraries for its many young residents.

In an effort to elevate these stories, our work has culminated in two virtual history museums, one for Cedar Riverside and the other for Near North Minneapolis. These online exhibits share community history, historic and ongoing harms of highway construction, and ongoing resistance and efforts to repair harms and restore communities.

Car culture and the ever-increasing demand for efficiency that supported the highway boom have diminished quality of life. Considering the foundation of these systems, which rely on the fracturing of some of the city’s most vibrant neighborhoods and continues to harm them, what can we imagine for a better shared future? Can we contest the speed based urban transportation logic that prioritizes moving quickly moving cars through urban communities at their expense?

Collage of historic photographs from the neighborhood: All images courtesy Hennepin County Libraries, except: North Country Anvil (Graytown, Stop Heller), Augsburg Archives (Trinity Lutheran Church), Mining Discovery Center (cross-dressers), Jessie Merriam (Edna’s garden sign, Mayday Books).