A new federal bill would someday prevent automakers from selling tall vehicles with huge blind spots that studies show are more likely to kill pedestrians, and give consumers the information they need to choose cars that better protect people outside them.

Recently introduced by Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon (D-Pa.), the Pedestrian Protection Act would, for the first time, require the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to mandate meaningful vehicle safety standards that consider how likely pedestrians and cyclists are to survive crashes with each car they test, including setting new benchmarks for "dangerous features like vehicle height and hood and bumper design" and the size of a car's blind zones.

The average U.S. vehicle has gotten eight inches taller over the past three decades, which experts say has helped accelerate a pedestrian death crisis that claimed 7,400 lives on U.S. roads in 2021 alone, and another 777 people in off-road spaces that same year. Driveway deaths among children who are killed by their own caregivers have become so common that the nonprofit Kids and Car Safety refers to the phenomenon as the "bye-bye syndrome."

Scanlon's bill would also require NHTSA to update the federal consumer safety ratings program to show exactly how safe a given car is for pedestrians and cyclists its drivers might strike relative to other models, and how good its blind zone rating is, so prospective car buyers can better compare their options. For now, neither rating would be included on the windshield sticker at the dealership, but they could be someday — and with the pedestrian death toll continuing to rise, there's no time to wait.

"Just the raw statistics make a really compelling case about the incredible, exponential rise in pedestrian and bicyclist deaths," Scanlon told Streetsblog. "Anyone looking at the streets sees that there is this increase in size across the board — and then you look at the data, and clearly, we need to do something in order to improve safety."

Scanlon's bill would patch over many of the holes in NHTSA's last proposal to update NCAP for pedestrian safety.

Following a mandate in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the agency pitched a new test in 2023, which would identify vehicles that are less likely to kill a pedestrian in a crash, including "front end shapes that would cause less harm (i.e., injuries) to a pedestrian if a vehicle hits that pedestrian."

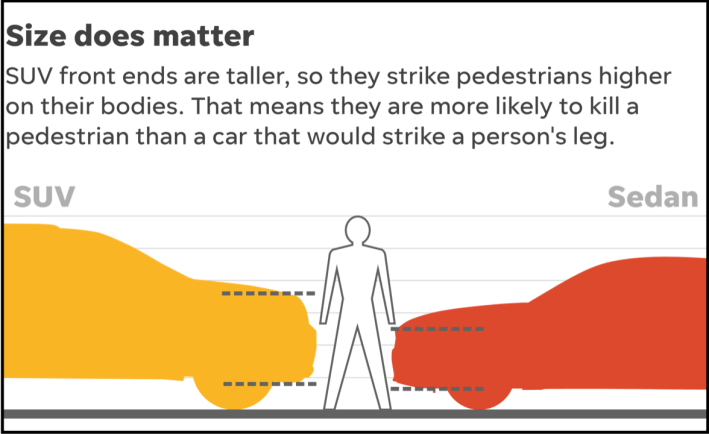

A growing mountain of research shows that cars with high front-ends and blunt profiles are way more likely to be lethal to people outside cars, because they tend to strike even tall walkers at the level of the head, neck, and vital organs rather than the legs. They're also more likely to push them under a car's wheels rather than up onto its hood.

But the new safety tests that NHTSA proposed would be totally voluntary — meaning automakers could simply opt not to evaluate megacars they expect would flatten a pedestrian crash-test dummy. They'd also be graded on a pass/fail basis, and some advocates fear the threshold for a passing grade wouldn't be high enough.

And even if carmakers did test their monster trucks or SUVs, a failing pedestrian grade wouldn't even affect those megacars' overall safety rating. Virtually all new vehicle currently receive four or five stars from NCAP, even as average vehicle sizes continue to swell and studies estimate that capping them at the size of a modest crossover could prevent 18 percent of pedestrian deaths a year.

Scanlon acknowledged that passing a bill to tame the megacar crisis won't be easy. The bill's likely path to becoming law runs through the next federal surface transportation bill, which won't be up for reauthorization until 2026, though she recommends advocates still call their reps now.

With extra-heavy "light trucks" like SUVs and pick-ups claiming 80 percent of the vehicle market last year — and automakers increasingly refusing to even make smaller cars — the cultural challenges ahead of the bill will be daunting, too. A former SUV owner herself, Scanlon understands many Americans' practical and emotional attachment to large vehicles, including her colleagues in congress.

But she also argues that times can change, especially as the research grows too alarming to ignore.

"We have a family; we have Labradors and kayaks, and in the past, we had soccer teams that we were transporting," Scanlon added. "So we've certainly owned some of these larger vehicles. ... But we do see cultural shifts happen over time. There was resistance to seat belts. There was resistance to fuel standards. There's always resistance to new things, but people do get the message eventually.

"If there are different standards that cars have to meet in order to not kill people — presumably the car manufacturers, which spend so much money on advertising and marketing, will figure out a way to do that really well," she continued.

This article was updated after receiving clarifying information about the bill from Scanlon's office.