Federal transportation leaders can reduce police violence against people of color on American roads by disincentivizing potentially deadly pretextual stops that don't actually curb car crashes, a coalition of leading progressive groups argues.

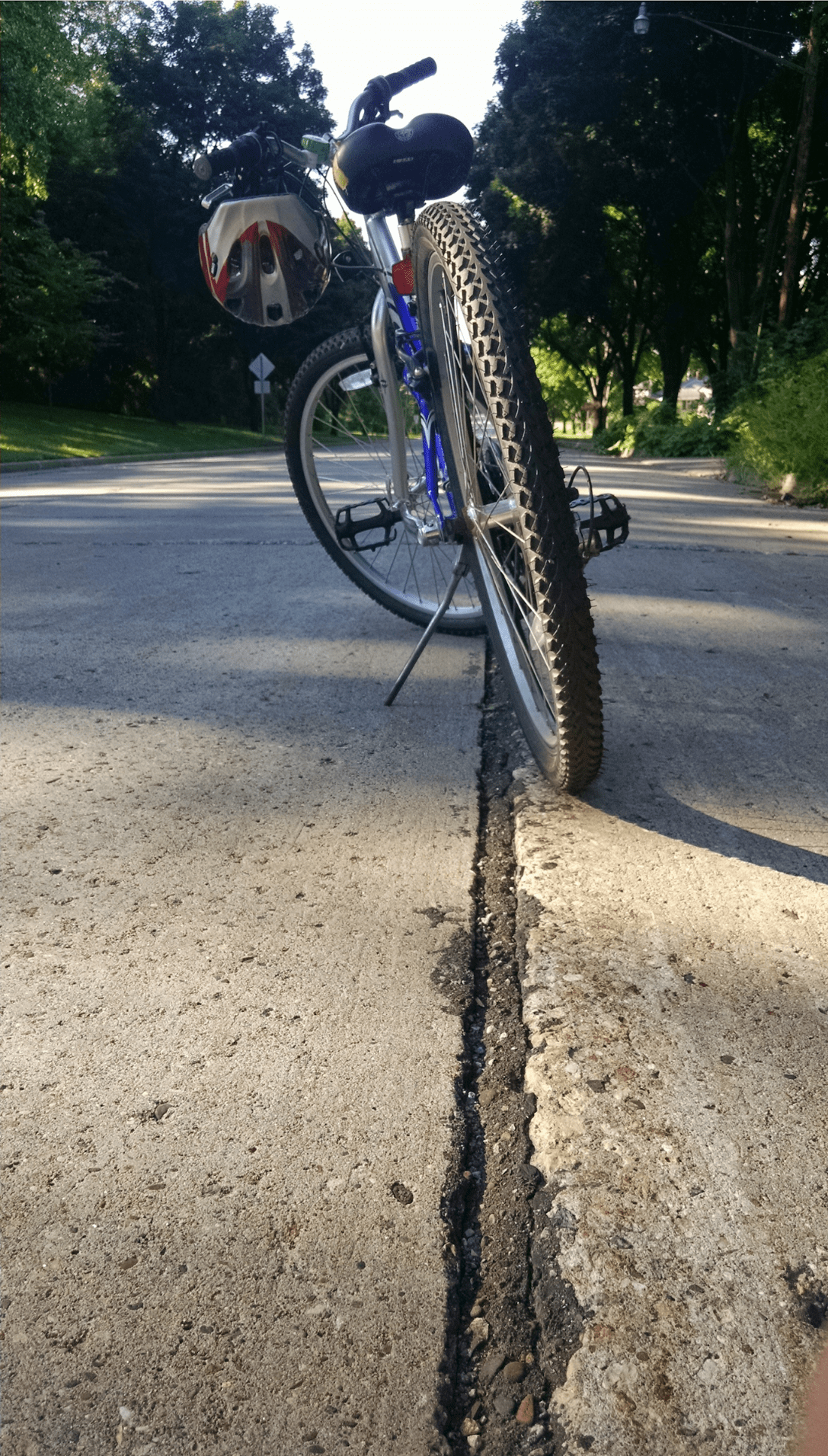

Researchers from the Center for American Progress, Color of Change and the Vera Institute of Justice analyzed how traffic stops for small infractions like cracked windshields and broken tail lights are continuing to explode on U.S. roads, often initiated by officers who hope to later find evidence of an unrelated crime — and found that many U.S. DOT policies are encouraging that troubling practice, despite the long history of police killing Black and brown road users during such encounters. (Note: while this report primarily focused on BIPOC motorists, similar stops of cyclists, walkers and transit users can escalate to harassment and violence, too.)

Because policing is generally viewed as a state and local issue, though, the researchers say federal transportation leaders are rarely held accountable for incentivizing those potentially deadly stops. And they say that's especially problematic since there's growing evidence that harassing drivers over things like broken equipment bears no relationship to curbing dangerous driving — even as it often has devastating consequences for people of color and low-income.

“Racial bias and racial profiling in traffic enforcement has been well documented,” said Rachael Eisenberg, managing director of rights and justice for the Center for American Progress. “And so without challenging those norms, that is, in practice, sort of accepting the status quo. [Federal transportation leaders] have an opportunity to leverage their authority as a grant maker — and as the entity that issues guidance and funds research — to challenge practices that have had really dangerous consequences, particularly for Black drivers.”

Perhaps the most obvious way that federal transportation leaders set the stage for those “dangerous consequences,” Eisenberg explains, is through guaranteed formula-based grants like the Highway Safety Improvement Program, which requires states to collect data on the total number of traffic stops they conduct and citations they issue in order to receive federal dollars, but doesn't set strong enough national standards for what other safety data they should be collecting. And without that, the departments of transportation and the public they serve can't easily identify when enforcement efforts are inequitable — not to mention whether or not they're actually reducing crashes.

As a bare minimum, the report authors say state jurisdictions (and their sub grantees at the local level) should be required to collect basic demographics for stopped road users, minimum details about the conditions of each incident, and which law enforcement actions followed, including use of force and searches — and they should have to share that data with the public, or have their grants rescinded.

“There is insufficient data flowing back to the DOT to help us have a national understanding of police traffic enforcement activities, despite the fact that DOT funding is supporting those efforts,” added Eisenberg. "The primary thing that we call for in this report is just the enhancement of the performance measures."

Even when it comes to discretionary grant dollars that aren't explicitly focused on enforcement, the report authors say that U.S. DOT could be doing more to reduce dangerous policing — especially by "invest[ing] in infrastructure improvements that can prevent crashes before they happen." That includes making it explicit to grantees that interventions like speed bumps — or, as they're sometimes known in the U.K., sleeping policemen — can and should be used as an alternative to human-based speeding enforcement.

The agency should also throw its funding muscle behind research that "identifies the most effective ways for police traffic enforcement efforts to curtail dangerous driving, specifically safety-related moving violations with the greatest role in traffic deaths and serious injuries" — because right now, they say, some of that evidence is lacking, or ignores the broader safety implications of bringing more police into contact with BIPOC communities.

“The evidence around the effectiveness of many of our current enforcement efforts is mixed," added Eisenberg. "And often, the impacts of having police engaged in enforcement are geographically contained, and limited in duration to when that enforcement activity takes place. … [Moreover, assuming that] one incident of police enforcement equals one less crash does not really take a holistic view of what it means to have safety on the roadways, especially for Black drivers.”

Moreover, U.S. DOT could direct its discretionary funding towards innovative policing alternatives, such as starting civilian enforcement units that are already being explored in a number of districts, driver speed feedback signs, and smart education campaigns. And they could source some of those ideas not just from jurisdictions that have "proved successful without relying on cameras or other punitive measures," like Hoboken, N.J., but from residents impacted by problematic policing themselves — and then uplift those voices to the country at large.

"There's a real opportunity for DOT to hear from people who have had these experiences," added Eisenberg. "Especially regarding how interconnected their safety from traffic crashes is with their safety from racially biased traffic enforcement. Because those two things are both significant parts of comprehensive traffic safety."

Editor's note: one quote was slightly amended at the request of the speaker.