Perhaps the only city in America to have completely ended traffic deaths on its streets is undertaking an aggressive effort to end traffic injuries, too — and its success may serve as a better model for small communities across America than the sprawling metropolises more commonly associated with Vision Zero.

And Hoboken, N.J. may have a thing or two to teach the big guys, too.

Last week, officials in the city of 60,000 just across the Hudson River from New York announced that they had begun the process of lowering speed limits from an already-pretty-safe 25 miles per hour to just 20, as part of its effort to end all forms of traffic violence by 2030. Studies have shown that just one out of four pedestrians struck by drivers traveling at 20 mph will be killed, compared to half of walkers struck by motorists doing 30 mph, and that the rate of serious injuries soars as cars speed up, too.

"Even though it might take an extra minute or two to travel across Hoboken in a vehicle, that extra time could very well end up saving the life of a child or senior citizen," said Hoboken Mayor Ravi Bhalla. "As a father of two children who walk our streets every day, the tradeoff is certainly worth it."

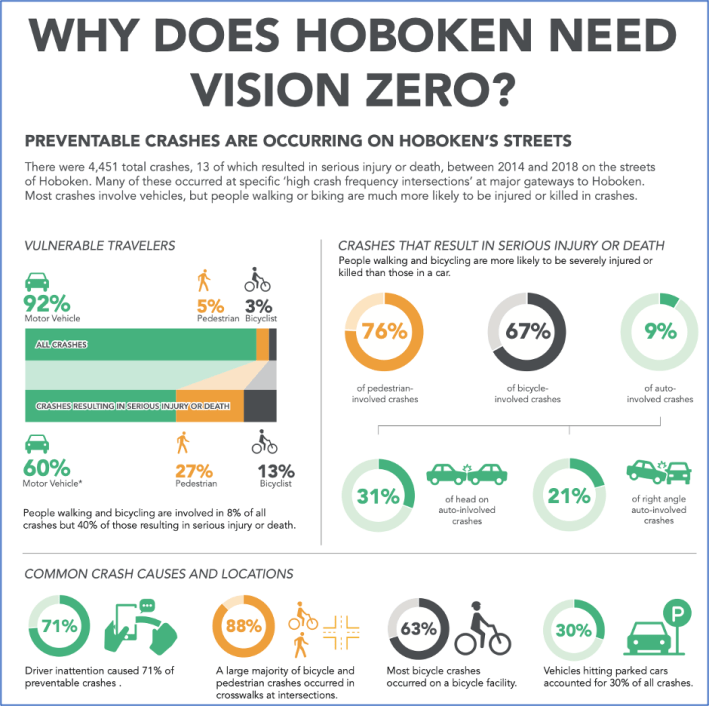

The move builds on the Mile Square City's earlier success at completely eliminating traffic deaths within its borders — a feat the community has accomplished for a stunning four years and counting, even as car crash deaths spiked nationally throughout the pandemic. And while Hoboken is certainly unique for how many people it packs into its modest footprint — it has the fourth-highest population density of any U.S. city, including neighboring NYC — Streetsblog could not find another U.S. community of comparable population or land mass that had achieved that goal.

Even its closest peer — nearby Union City, N.J., which is identical in geographic size but home to about 70,000 people — has reported multiple deaths over the same period.

That accomplishment caught the attention of federal Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who referenced Hoboken as evidence that America could achieve Vision Zero as part of its path-breaking National Roadway Safety Strategy last year.

Local officials, though, say they won't rest on their laurels — because the work of keeping streets safe is never truly done.

"We know this is just a snapshot in time, and at any point in time we could regress. That’s actually the most likely scenario," said Ryan Sharp, Hoboken's parking and transportation director. "It’s incumbent upon us to continue to push forward and not just accept that things have improved, put our pencils down, and quit. There are still plenty of traffic safety hazards that exist in Hoboken; it’s our responsibility to continue to chip away at them."

"Chipping away" at traffic danger is perhaps the best way to describe the tactics at the heart of the Vision Zero strategy in Frank Sinatra's hometown — though the sheer impact of those small moves has been astonishing.

Rather than spending millions to add a protected bike-lane to every street or permanently closing vast swaths of the city to cars, Sharp and his colleagues focused on more modest strategies like "daylighting" corners so parked cars don't block motorists' the view of pedestrians in crosswalks, and building modest curb extensions to shorten the distance a walker has to share space with motor vehicles. That's a cheap and hugely impactful step that even larger cities like New York, which refuses to enforce its own daylighting law, often fail to take.

More expensive interventions, like raised intersections and road diets along the city's High Injury Network where most crashes occur, are typically bundled into scheduled repaving projects funded largely by the state DOT — meaning that despite its relatively affluent tax base, Hoboken is not dependent on local wealth for its essential infrastructure safety upgrades.

Critically, the city also isn't depending on enforcement to slow drivers down. Sharp says that the new 20 mile per hour speed limits will be reinforced by infrastructure changes that intuitively signal drivers to slow down — something other cities have been criticized for not doing comprehensively enough — and that local and county police will focus on educating the public about the new law rather than cashing in on newly-created speed traps, at least until the policy becomes broadly known. That doesn't mean that advocates shouldn't be vigilant — especially considering that New Jersey state law currently does not allow for automated speed enforcement — but it does mean that city leaders are being mindful of the inequities of traffic enforcement on people of color, even as they strengthen local policies.

"This is not intended to be some kind of Draconian new law that is designed to ticket a lot of people," said Sharp. "There are some people who think this is gonna be some cynical ploy, but really, it's mostly about education."

It will take time, but not as much time as you might think. The biggest factor is political will. Hoboken is only 60k people but a lot of these investments are relatively cheap to implement.

— Ari Méndez (@atmendez) July 11, 2022

Zero traffic deaths since 2018. https://t.co/4rMYJNLXXv

Sharp acknowledges that other cities will need far a more extensive and expensive reimagining to achieve their Vision Zero goals than Hoboken, and that he and his colleagues didn't have to radically transform their city's pre-war urban fabric to turn it into a more human-centered place. Still, he says that ending traffic injuries won't be without its challenges — including political and financial ones, which can be particularly onerous in close-knit places.

"There’s no anonymity in a town of 60,000 people," Sharp said. "Even very small, acute changes can create a big response from the public that demands a big response from the city ... So we definitely have similar challenges as other communities, especially in terms of budget and things like that. We still had to ask ourselves: How do we find the money to create a Vision Zero action plan? How do we find the money to build it, and to hire enough people to stay on top of it, not to mention to stay on top of the metrics year after year?"

Sharp emphasizes Hoboken's success in clearing those hurdles — and getting the city council to approve the new speed limit law unanimously to boot — should prove to other small communities that even the most ambitious traffic safety initiatives are within reach. And it should also prove to neighborhood-level leaders in big cities that small changes are worth pursuing.

"For Vision Zero to really take the next step at a national level, we have to start finding a way to bring smaller cities into this work," Sharp said. "Because right now, Vision Zero has this brand that's associated with very flashy, huge street redesigns in the biggest cities in the country. So of course, a lot of these smaller communities are saying, 'Bus lanes would never make sense here,' or 'what’s a bike signal?' But we don’t necessarily need these innovative, bleeding-edge solutions to make a huge difference."