A recently destroyed pedestrian bridge that runs over an urban highway will be rebuilt, the Washington, D.C., mayor has announced, ignoring calls from advocates to reimagine the road instead, which has become a symbol of systemic racism in the region.

The Lane Place pedestrian bridge over freeway DC-295 was rated in "poor" but passable condition even before a mack truck collided with the structure, pulling it loose from its moorings and causing its collapse. Six people were injured in the June 23 incident, and residents of the majority-Black neighborhoods flanking the highway lost access to one of the few safe routes to jobs and essential services on the other side.

Yet Mayor Muriel Bowser's announcement that she would rebuild the structure — at the eye-popping cost of $25 million — may set a troubling precedent for other cities, which advocates say should rethink walking infrastructure that privileges the convenience of drivers. The news was met with a skeptical response from local leaders, some of whom called for the corridor to be reworked around the mobility needs of the predominantly Black surrounding community — especially since impending national legislation may give cities federal dollars to cap or even tear down urban freeways such as DC-295.

"Many folks have been speaking out for years,” said Advisory Neighborhood Commission member Anthony L. Green at a D.C. council meeting covered by the Washington Post. “They’ve been telling you that they live on an island, that they’re trapped behind a highway. And the only way that you really can get over there is drive over there or, you know, roll the dice apparently to get over one of the pedestrian bridges.”

Almost half of residents in the neighborhoods served by the Lane Place bridge do not have access to a private vehicle, and they have the highest rates of household poverty in the District.

On scene at the pedestrian bridge collapse in NE, over 295 @WTOP pic.twitter.com/Ar8IbDsyY4

— Michelle Basch (@mbaschWTOP) June 23, 2021

D.C. officials stress that the collapse of the Lane Place Bridge was a tragic but anomalous event, since the 65-year-old structure lacked the 17.5 foot clearance necessary to accommodate modern-day semi-trucks. But the debate over its future echoes a much broader national dialogue about redressing the lasting damages that urban highways have on BIPOC communities — even if those highways do have marginal accommodations for walkers, liek pedestrian bridges.

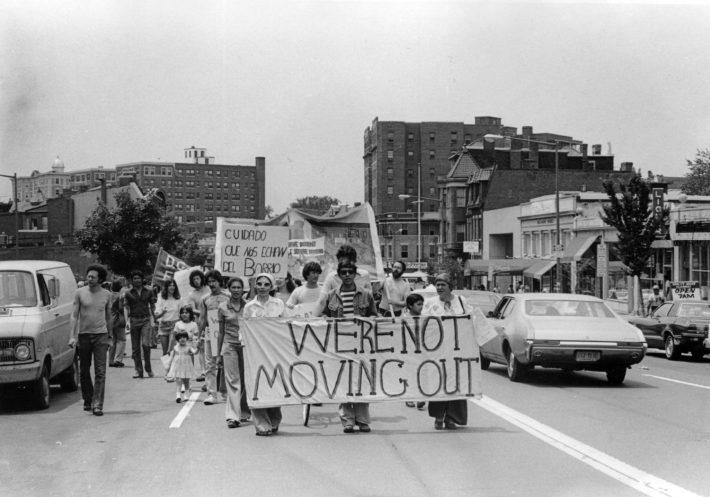

Also known as the Anacostia Freeway, DC-295 was built with funds from the Federal Highway Act of 1956 before later being re-designated as a District of Columbia road, and its planning followed many racist patterns that plagued the infamous national program. Planners deliberately routed the road through the heart of several predominantly Black neighborhoods in the name of "slum clearance," providing an easy path for White residents to flee the city and settle in suburban Prince George's County, Md.

"When this highway was built, it was absolutely to promote white flight," said D.C.-based urban designer and planner Jonathan L. Bush, who authored a paper on how authorities might atone for the road's racist effects. "To this day, DC- 295 acts as a separator. It takes majority African American communities that have been historically underserved for more than 60 years, and it separates them [from opportunity and essential services] ... A lot of the people in these neighborhoods can step out of their homes and see a grocery store, but they can only get to it by getting in a car."

Bush says he supports efforts to rebuild the Lane Place bridge in the short term in order to restore residents' access to critical destinations, but that the entire design of the corridor must be rethought in the long term — and not just the highway itself.

"Even if more of those pedestrian linkages existed, the regulatory environment [related to land use] in this area doesn't allow development to naturally occur where these pedestrian linkages would land," Bush adds. "When you come out of your front door, should there really be a car dealership next door, or an auto mechanic shop? Or should you have access to a grocery store, good schools, clean air to breathe, places to recreate? These are folks who can see the Anacostia River, but they can't even access it [because of the highway.]"

But some advocates fear that D.C. doesn't want to do that critical work along MD-295 — especially given the hefty price tag of the bridge rebuild.

"I think this is a great test of what it means to 'build back better,'" said Joe Cortright, an urban economist and author who has argued against the proliferation of pedestrian bridges over more human-centered approaches to walking infrastructure. "The way our infrastructure decisions are presented is that we're always doing piecemeal, remedial patches to the existing flawed system. DC will spend it looks like $25 million to rebuild back something that is at best a kind of band-aid ... Once you've spent $25 million 'fixing' this pedestrian bridge, you've essentially committed yourself to the indefinite future of the freeway it crosses."

As Congress debates a series of infrastructure packages that include billions for innovative urban highway removal projects, advocates hope that D.C. will rethink its commitment to the status quo — and that other cities will, too.

"Professionally, I think this whole corridor needs to be reimagined as soon as yesterday," Bush laughs. "But whatever the future holds, it needs to prioritize the people who already live in this area staying in place, while giving them more multimodal options to get around."