It's official: road users who ventured outdoors during COVID-19 lockdowns had a greater chance of being killed than any time in the past 15 years, despite historic declines in driving — suggesting that the real problem remains streets that are designed only to move cars quickly.

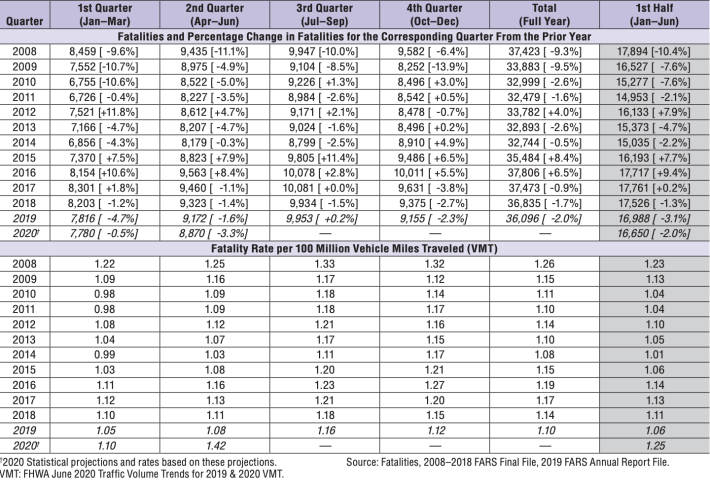

The rate of roadway fatalities skyrocketed to 1.42 deaths per 100 million vehicle miles traveled in the second quarter of 2020, according to the National Highway Safety Administration's just-released report. The rate was just 1.08 deaths per 100 million miles over the same period last year — a five-year low. This year's spike represents a 32-percent increase.

The data cements the findings of street safety journalists who have speculated for months that rising state and local fatality rates were signs of a bloody national trend — including Streetsblog, which has reported on the phenomenon since the beginning of citywide lockdowns. Traffic violence experts have consistently attributed the death toll to our nation's penchant for road designs that induce drivers to speed when roadways are empty — and many roads were indeed wide open because of the pandemic.

“We do have fewer car crashes right now, because there are fewer cars,” said Jacque Knight, a St. Louis-based traffic planner, told Streetsblog back in March. “But the crashes we do have are likely to be more severe because speed is the biggest determinant of serious injury and mortality — especially for pedestrians. Our hospitals can’t handle that right now.”

With so many fewer cars on the road, the raw number of deadly crashes did decrease during the height of quarantine orders, but not by very much. NHTSA reports that 8,870 people lost their lives on U.S. roadways between April and June of this year — just a 3.3-percent decrease over the same period last year, despite declines of driving of as much as 94 percent in many areas of the country.

Unfortunately, the federal agency blamed the bloodshed on everything but bad road design. In an exclusive to Reuters, a spokesperson for NHTSA speculated that “drivers who remained on the roads engaged in more risky behavior, including speeding, failing to wear seat belts, and driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol,” but provided no evidence that those behaviors increased during the second quarter. Speeding, of course, was indisputably on the rise this spring, but that was likely less a matter of individual drivers exercising bad judgment than the systemic impact of wide open roadways inducing drivers to go too fast.

One reason the Administration might not have that data is because law enforcement officers largely didn't stop bad drivers during the early days of the pandemic, which departments attributed to the need for officers to practice social distancing. NHTSA also speculated to Reuters that it was "possible that drivers’ perception that they may be caught breaking a law was reduced.” There's no definitive data to disprove that yet, but it bears repeating that America's heavily policed roads have never really succeeded in curbing our traffic violence crisis at any point in modern history — and have precipitated an unacceptable police violence crisis among communities of color.

Infrastructure-based solutions, of course, do have a proven track record of saving lives without increasing interactions between the public and police — and since traffic volumes may not rebound to pre-pandemic levels ever, it's past time to put our money and energy behind what works.