The Vision Zero Network — perhaps the single most influential street safety advocacy group — has pledged to no longer recommend police enforcement as strategy to make streets safer. But many street safety advocates are still reckoning with what that might mean — especially if they've never been challenged to question white supremacist structures before.

The statement came in direct response to the Black Lives Matter movement and our national conversation about police violence against black people, particularly when that violence acts as a barrier to the free use of public space. But the statement did not provide a comprehensive framework for street safety advocates to imagine what a safe street might look like without cops.

Of course, visionary Black activists like Mariame Kaba and Angela Davis have been working tirelessly to imagine just alternatives to our heavily policed society for decades — but those voices haven't always reached the ears of the powerful, much less been implemented at any large scale in our cities. And if we continue to fail to actively listen to Black, indigenous, and other people of color who have been having this conversation for years, they never will.

Here are just four of the best examples of how the #DefundThePolice and #AbolishThePolice movements could make streets safer and make traffic enforcement better.

Enforcement without a gun

"Defund the Police" doesn't necessarily mean ending law enforcement in all forms. (Though some think it should! More on that later.) And when it comes to traffic safety, perhaps the most obvious alternative to the traffic cop has a model in many of our cities already: the humble parking attendant.

"Enforcement doesn’t have to include the police — or even, specifically, the branch of the police with a badge and a gun," said Warren Logan, policy director of Mobility and Interagency Relations for the City of Oakland. "In our city, for instance, we rely on parking enforcement officers that don’t have weapons, because they don’t need weapons. We did that deliberately, because we asked ourselves: how many interactions do people of color really need to have with armed police?"

Why did Rayshard Brooks have to lose his life? pic.twitter.com/X1oYExUMQl

— The Daily Show (@TheDailyShow) June 16, 2020

Proponents of police disarmament argue that by giving badges and police salaries to social workers, mental health counselors, addiction specialists, and other unarmed, specially trained professionals, departments can serve the public in a way that prevents crime in the first place. And doing so could also cut down police funding; bloated weapons budgets are a major reason why police budgets gobble up such a high percentage of city revenues in many communities.

Enforcement without a gun or a badge

Disarming and demilitarizing police forces in the traffic control realm could be a good first step that's consistent with the goals of the #DefundThePolice movement. But many activists argue we must go even further — and remove the entire institution of the police from traffic control altogether.

"Even if we trim the budget ... we're still invested in policing as an action, institution and method of meeting need and reducing conflict," Andrea Ritchie, author of "Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color," said in a recent interview.

That's why many #DefundThePolice advocates argue that we must reduce the number of police officers in our cities, period — and shift the resources we previously spent on those officers to the non-police-affiliated members of our government who are better equipped to meet the real needs of Black communities.

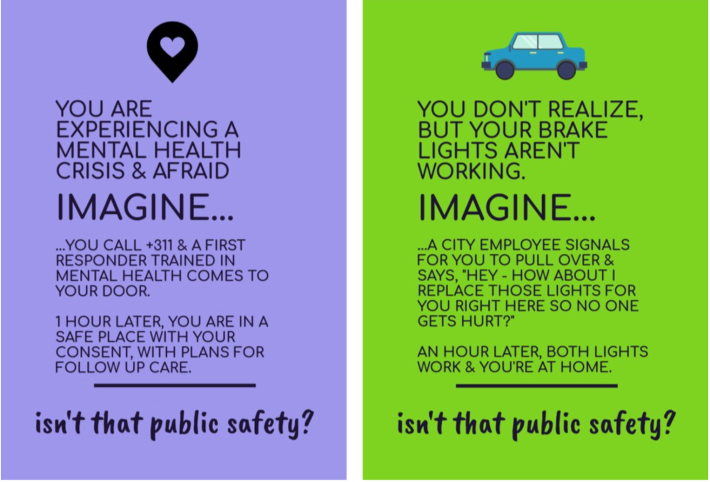

In the traffic safety realm, that could mean, for instance, replacing even unarmed cops with non-police mental health responders to respond to pedestrians in crisis. Or sending a city-employed mechanic to help you fix a brake light on your car when it burns out, rather than writing you a ticket for failing to do it yourself.

Further many advocates say it's not just a matter of getting the cops out of street enforcement — because taking administrative tasks traditionally relegated to police and shifting them to departments of transportation can go a long way, too.

"Right now, I’m supervising a program for outdoor dining program in response to COVID-19," said Logan. "Normally, [when a restaurant owner wants to put a table in a parking spot or on a sidewalk], they have to file for an encroachment permit, and they have to engage with police to get that. But we realized the other day that if we let restaurant owners do that through an obstruction permit, we can give them the tools they need through our own office. It's about asking: why is it that we cause people to have to engage with the police for this stuff? We don’t have to pass you along to the police. So let's not do it."

Enforcement without an officer at all

Traffic cameras are another way to enforce traffic laws without putting an armed officer into a community — but they're the subject of hot debate.

On the one hand, speed cameras have drawn criticism in cities like Washington, D.C, Philadelphia, Ferguson, and other communities across America when local governments disproportionately deployed them in Black and other non-white neighborhoods, in a move that activists decried as an effort to pad city revenues at the expense of minority community wealth. Moreover, a 2018 MIT study showed that facial recognition systems like the kind found in speed cameras mis-identified darker-skinned women 34 percent of the time — a stunning margin of error that could lead to Black women being penalized for moving violations that they didn't actually commit, simply because another person was driving her car.

On the other hand, speed cameras have, historically, been even more unpopular among police unions, which argue that traditional traffic stops performed by armed officers are necessary combat drug and gun crimes — a policy that, when paired with racial profiling, has lead to mass incarceration and extrajudicial police killings, disproportionately of Black men, women and gender nonconforming people.

Still, many advocates stress that all traffic safety tools have the potential to be used in service of white supremacy or Black liberation, depending on how they're used — and we must stay vigilant of racist applications of speed cameras.

"Once someone is in police systems, they’re a suspect for life, leaving them open to further persecution at the hands of the law – even if the only reason they’re thanks to police error," said journalist Moya Lothian McClean in a recent article. "This is how criminalization of black and brown people works, and the rollout of flawed facial recognition tech is only going to speed up the process."

Cutting an 'E' from Vision Zero

The Vision Zero Network's statement didn't go so far as to totally divest police enforcement from the "Five E's" framework that guides the program — so far, they're only committing to exploring "alternative" enforcement measures, as well as stressing engineering, education, evaluation and encouragement strategies that could prevent traffic violence in the first place.

Still, it's a step in the right direction. And most important, it follows the lead of Black planners and engineers across the nation who have been saying for years that enforcement should be a tool of last resort — if it's a tool at all.

"One of the things that I think about as a transportation planner is, what are the designs which are self-enforcing?" said Logan. "Let’s not create a space that requires police engagement to reflect the type of behavior and interaction you’re looking for. Do you have to engage the police with this to get it done? Can we just get that out of design?" (In New York City, the group Transportation Alternatives has been focusing on this topic, too.)

Under an enforcement-free paradigm, a city might still have speed cameras in areas where drivers go too fast. But they would never be used to issue citations to pad a city budget without really deterring speeders, as some cities do; they would be used to give engineers the data they need to redesign dangerous intersections to actually slow drivers down.

Even drunk driving, activists argue, simply isn't curbed by the threat of police enforcement — so much so that one city in Canada is considering decriminalizing it altogether. A different, criminalization-free model might involve taking traffic stops out of the hands of cops, and putting them in the hands of addiction specialists who are trained in deescalation strategies and equipped with the tools to get problem drinkers meaningful help and a safe ride home. And the data on drunk driving stops, especially if many drivers are caught drunk behind the wheel in a single corridor, might prompt the city to invest in affordable housing near restaurant districts — so it'd at least be feasible to walk home from the bar.

"The solution to drunk driving is not policing. It's transit," said Logan. "It’s walkability. It's giving people other options besides driving to get home."