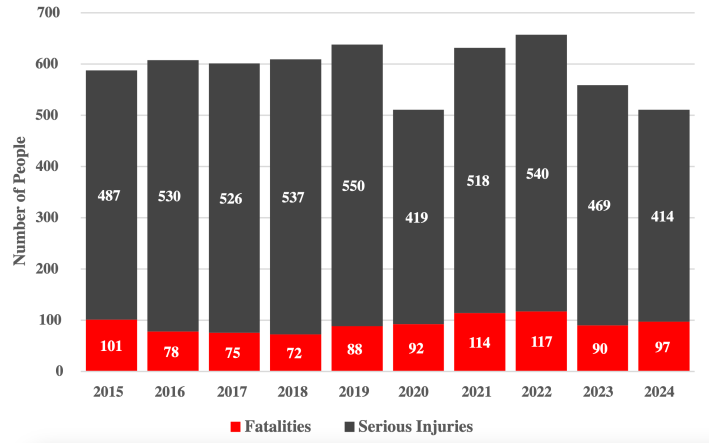

On paper, Austin has a long way to go towards Vision Zero. At least 75 people have died on the road in each of the 10 years since the Texas capital formally pledged to eliminate traffic fatalities and serious injuries; in 2024, 97 people were killed, an uptick of seven deaths from the year prior that city transportation officials say was avoidable and unacceptable.

As those same officials look back over the last decade, though, they also say there's a deeper story behind the statistics that deserves to be heard — especially by those growing impatient with the country's slow progress to curb traffic violence. There have been under-the-radar successes in Austin that could help other cities weather the state and federal headwinds that virtually all cities will battle in the years to come.

"Our long term goal is always going to be zero, and over these first 10 years, obviously, we haven't achieved that," said Joel Meyer, Austin's transportation safety officer. "But when you look closer into the numbers, you can really see that where we focused our resources — and especially our infrastructure funding — we're seeing pretty significant reductions in injuries, fatalities, and comprehensive costs.

"One of the messages we're trying to stress is: this is just the start," he continued.

Meyer explained that Austin was among the first cities in the U.S. to embrace Vision Zero in 2015 — preceded only by New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, who all claimed membership in the Swedish safety movement in 2014 — but it took time for the fledgling effort to take root. And he acknowledges that those roots will need to grow much deeper before completely ending traffic violence in Bat City is a real possibility — even if, in many ways, the city's efforts are already bearing fruit.

Between 2017 and 2020, for instance, Austin overwhelmingly voters approved a staggering $95 million for transportation safety improvements across three consecutive bond measures, powering the completion of 29 major intersection redesigns along with dozens of street lighting and speed management efforts, not to mention well as hundreds of traffic signal upgrades and other changes.

The sheer scale of those efforts would be massive in most communities. In a Texas-sized one with 2,800 miles of streets largely built around the automobile, though, it'll take time to fully carpet the city in life-saving concrete, not to mention the far harder worker of building a government that can support that work.

Meyer stressed that most of the impactful wins over the last 10 years were unsexy foundational changes, like updating comprehensive plans, revising city policy documents governing street design, assembling cross-department work groups, and mapping out the city's High Injury Network to guide where investments would have the most impact. Most of those moves aren't visible to the public, but they're foundational to the infrastructure efforts that are growing too omnipresent to ignore.

"Here in Austin, it's really been a story of gradually growing our operational and capital budgets, adding staff, building capacity internally," added Meyer. "[I think that's part of why] we've seen three consecutive elections where the public has overwhelmingly passed bond referenda specifically for Vision Zero safety projects, along with other kinds of mobility projects. There's a level of trust that I think we've built with the community, [that we'll use] these public dollars to implement projects that really improve people's lives."

That trust, though, is tested every time another person dies on Austin roads — even if those roads aren't under the city's control.

Meyer and his colleagues point out that about 70 percent of the traffic fatalities in the state capital occur on roadways controlled by the Texas Department of Transportation, compounding a statewide crisis that's seen at least one traffic death every day for 25 years, and an average of 11 daily deaths in 2024 alone.

Experts blame that carnage, in part, on the state transportation's agency's explicit and implicit emphasis on increasing driver speeds, like requiring communities to set highway speed limits at least 70 miles per hour and allowing speeds up to 85 miles on one roadway segment — the highest speed limit in the entire U.S.

That focus on speed extends onto highways and arterials in cities, too, which safety-minded city officials often struggle to resist thanks to structural forces like ultra-permissive state preemption laws. Meyer, though, argued that cities still have the moral responsibility to fight for Vision Zero — even when sometimes, it feels like their efforts are being undermined from above.

"A lot of times, the traveling public doesn't really know or even care which agency owns the roadway. [They just know that] these fatalities are happening in our community," he added. "And so as a local government, we think we have the responsibility of doing everything we can to try to improve safety, regardless of who owns the facility."

That fight is getting even harder as winds change in Washington. Austin won billions in safety funding under the Biden administration, but some of those grants face an uncertain future under President Trump, who's attempting to claw back much of the discretionary money awarded by his predecessor — and life-saving projects like bike lanes are being particularly targeted.

The administration's war on diversity, equity, and inclusion has made applying for future grants challenging, too. Like most large cities, Austin's traffic violence crisis disproportionately impacts people of color, people in low-income neighborhoods, and people without homes, a fact that city leaders feel a moral duty and a practical imperative to confront as they prioritize projects that will save the most lives — even if federal grant makers might ding their applications for even mentioning the social demographics at play.

Add in longstanding problems like lax federal regulations on large SUVs that are deadlier to pedestrians and a global pandemic that upended traffic patterns across America, and Meyer says that sometimes cities face an uphill battle towards achieving Vision Zero, even if U.S. DOT is ostensibly committed to building "safe systems."

"We're still at a point where cities are leading the way with Vision Zero," Meyer added. "But I think our challenge is, how do we scale that up to bring more people along with us? How do we get our state governments — and the federal government — to really change how they do things, orient around this idea of Vision Zero and safe systems?"

Even against those odds, though, there have been glimmers of success in Austin's first decade of Vision Zero — and collectively, they're already beginning to shine.

Meyer said that the 29 major intersections that got the Vision Zero treatment so far have experienced a 38-percent reduction in serious injuries over the last decade, helping drive the city's injury rate to the lowest level last year since the program began. That's also equated to $78 million saved in annual crash costs, which has helped the city win over skeptical residents who don't believe that saving every life is possible — but do believe that saving money is essential.

"Even if the the idea of zero fatalities and serious injuries is hard for people to wrap their heads around, when they see a crash, I think a big portion of the community can understand how much congestion that's going to cause, and how much property damage there could be, how much police and emergency response resources have to [be deployed]," Meyer adds.

And Austin is also evolving its own approach, emphasizing whole-city issues like lowering speed limits rather than focusing on dangerous corridors alone. Every little bit of effort changes the city's culture in a way that won't be easily undone — just like the slow march of car culture has gradually transformed the country into what it is today.

"It took decades of car-centric planning to get to this point where we have 40,000 traffic fatalities every year in this country," he said. "We're not going to get to zero overnight. This requires change at all levels of government, across nonprofits, across the private sector. ... [But] if we can show that where we focus our resources, [we see] benefits, it will get easier to tell the story of how over time, these numbers are going to come down — and how we can eventually get to zero."