Uber and Lyft have long promised that their services would "free" people from private car ownership — but data show the opposite is happening.

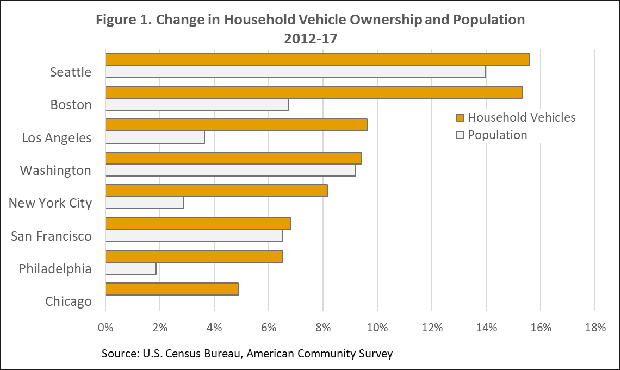

Census statistics show that in the eight major cities where Uber and Lyft are most concentrated, total car ownership has risen in the last five years — a worrisome reversal of earlier trends, transportation consultant Bruce Schaller wrote this week in CityLab.

In many cities, there was an increase in car-free households and car-light households — households with fewer cars than workers — between 2012 and 2017. But those reductions were eclipsed by growth in "car-rich" households, as Schaller calls homes with more two or more vehicles.

"Increased car ownership in America’s most walkable and transit-oriented cities is a deeply worrisome reversal from what came before," Schaller writes. "From mid-2000 to 2012, transit ridership increased while car ownership grew slowly, if at all. But now car ownership is expanding faster than population."

Uber and Lyft have worked hard to promote themselves as green alternatives to automobile ownership. But data are making it increasingly clear these companies are adding cars to the roads in our most congested cities, and undermining transit.

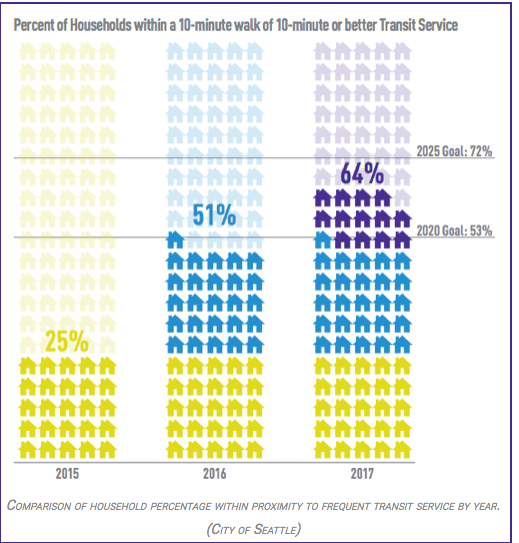

The one city that did make progress in increasing the number of car-free and car-light households was Seattle, where such households increased 23 percent over the last five years. The city has also enjoyed a sizable increase in transit ridership over the last few years — which it has achieved by investing heavily in rail and by expanding bus service hours dramatically.

But, concerningly, even in Seattle, vehicles grew faster than population, 14 versus 12 percent.

San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Chicago all had growth in car-free and car-light households. It stayed about the same in Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C.; and in Los Angeles, car-light and car-free households actually declined.

Of course it can't all be blamed on Uber and Lyft. In the last five years, an economic recovery and low gas prices have encouraged more lower-income Americans to buy cars. But Uber and Lyft aren't going to save us, Schaller says. In fact, the presence of these companies makes investing in alternatives all the more urgent, he says:

Amid the many modes that can help out, we need to focus above all on one particular way for people to share the ride. But it’s not some new form of "shared mobility." It’s frequent, reliable, safe, and comfortable public transportation.