Automatic emergency braking systems are getting better at detecting pedestrians, but they're still struggling to see walkers in the dark conditions where people are most likely to die — and, in some cases, wearing high-visibility clothing could actually make the technology less likely to spot a person strolling in the dark, a new study finds.

Adding to the mountain of evidence that automotive technology alone won't end America's pedestrian death crisis, researchers at AAA found that the most recent Pedestrian Automatic Emergency Braking systems — or PAEB — failed to detect an adult-sized crash test dummy about 40 percent of the time after dark, even though the test vehicles were only moving at around 25 miles per hour under "ideal conditions."

That speed, which is a common limit in neighborhoods across the U.S., is far slower than most drivers are actually going when they kill a walker. More than 80 percent of pedestrian deaths in the U.S. occurred on roads with speed limits of 35 mph or greater between 2018 and 2022; other studies, meanwhile, have found that PAEB performs even worse the faster a car is going.

"[PAEB technology has taken] a big jump forward, but it's not 100 percent like we'd like to see," said Greg Brannon, AAA's director of automotive research. "US traffic fatality statistics are an embarrassment, especially when you compare them to other developed countries that continue to to reduce the number of traffic fatalities while the US has remained steady or, on some years, increased. Seeing 40,000 people dying on the road in the US — it's just not acceptable."

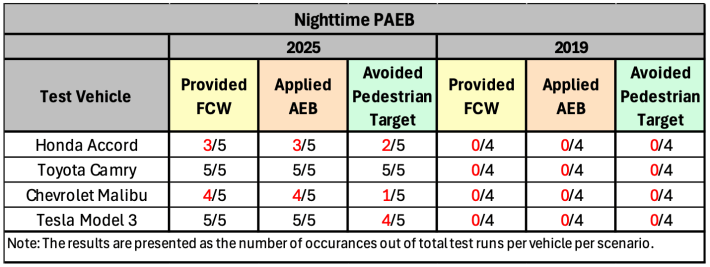

To be fair, PAEB was a lot better than the last time the organization road-tested the technology in 2019 — even If it wasn't good enough.

Back then, no car's emergency braking system could reliably avoid even a single a collision with a pedestrian dummy under nighttime conditions at 25 mile-per-hour speeds, "rendering them unreliable when needed most," the report authors wrote. Today, thanks to "advancements in sensor technology and processing algorithms," all of the cars avoided at least one crash out of six test runs — though some, like the Toyota Camry (which scored the highest) performed better than others, like the Chevy Malibu (which scored the lowest.)

Despite those promising improvements, though, the researchers say that the auto industry's slow progress is yet another reminder not to entrust our safety future solely to machines — especially when 7,318 pedestrians were killed by drivers in 2023 alone, and 77 percent of them were struck at night.

In an ironic twist, Brannon and his colleagues found that outfitting dummies with the kind of high-visibility gear that DOTs constantly encourage walkers to wear in PSAs appeared to actually make the automatic braking technology worse at detecting walkers' presence, at least on some vehicle models like the 2024 Honda Accord.

Even more damningly, the specific type of high visibility gear that the researchers tested is commonly worn by construction workers, first responders, and the kind of roadside assistance workers AAA deploys every single day.

"You cannot trust that donning that-high visibility clothing will keep you safe," Brannon added. "It may help, and does seem to help with human drivers, but these more-automated systems don't react to it like a human driver ... The industry loses a roadside assistance provider every other week, on average; somebody is not able to go home to their family after work. That is a terrible, terrible situation, and that's why it's so important that we get this right, and get it right soon."

To reverse the pedestrian death crisis after dark, the AAA researchers want regulators to improve how they test the PAEB systems they recommend to consumers through the New Car Assessment Program to incorporate more nighttime scenarios and conditions, including putting dummies in high-viz clothing.

Because if they don't, automakers have little incentive to improve their technology on their own, Brannon says.

"What we've seen doing this for over a decade now is that automakers are getting better at passing the standards, and they're doing a great job of testing to those standards ... [but] you go outside of those standards, and the performance is less effective," he added. "Our hope for regulators in particular is that they continue to push forward on nighttime testing — including those vulnerable roadside workers who are out there, literally, with their lives on the line."

More important, though, Brannon says it's critical that we shake off our automation complacency and look beyond technology to solve the pedestrian death crisis — starting with the oldest solutions in the book. That could include obvious fixes like more lighting and wider shoulders, but also holistic approaches, like redesigning roads to discourage dangerous driving, and building cities and transit systems where fewer people need to drive, period.

"We need to not only have safer cars, we need safer drivers, and we need safer roadways in general," Brannon added. "To address this crisis that we have in the United States, will take a safe system approach."

In the report, his colleagues were even more blunt: "Relying solely on vehicle automation for pedestrian detection and collision avoidance is not advised."