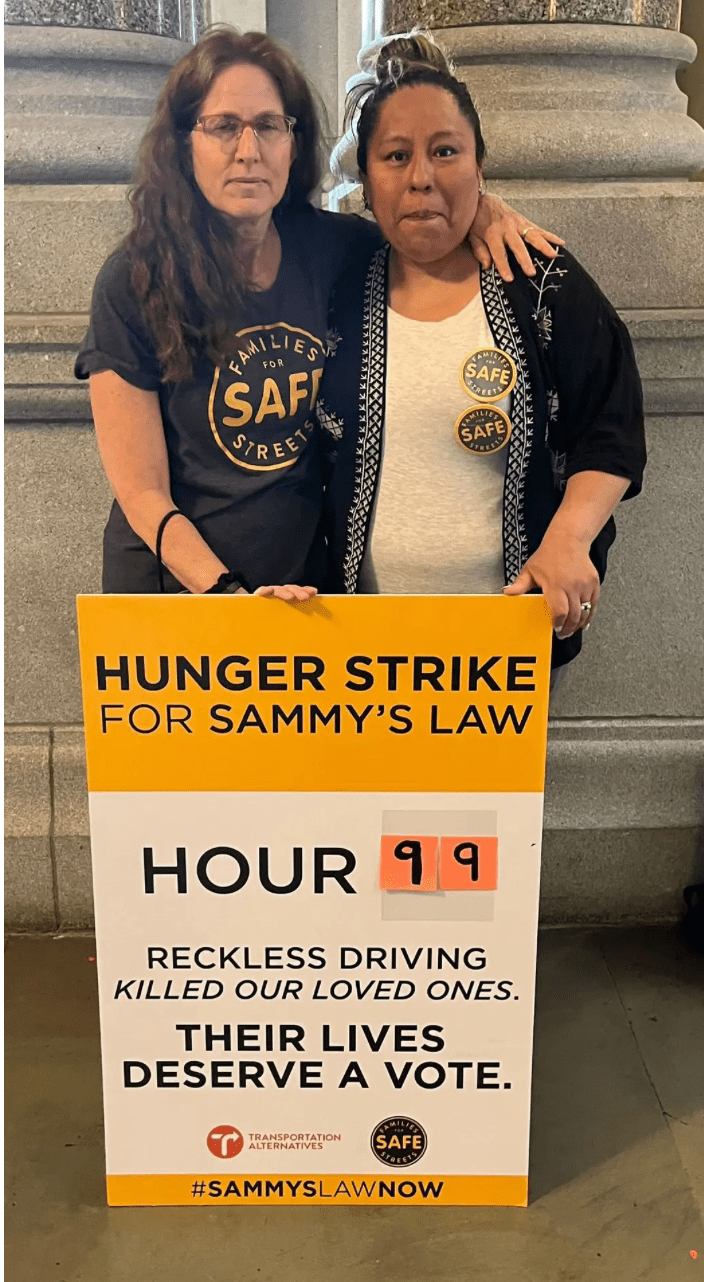

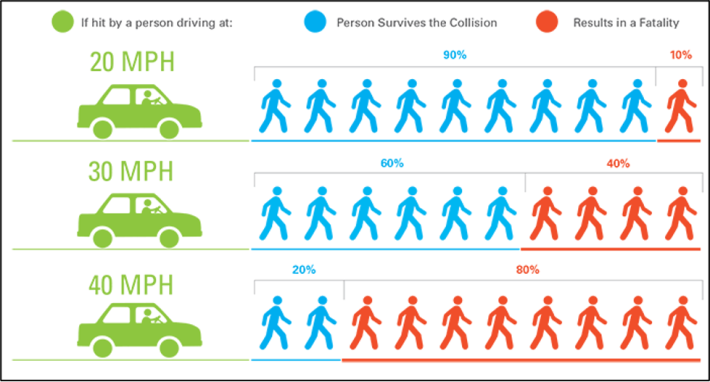

In June of 2023, three mothers who lost children to traffic violence began what would end up being a historic hunger strike on the steps of the New York State capitol. Their demand to their legislature was a simple one: pass a long-stalled bill that would allow New York City the option of lowering speed limits to 20 miles per hour — a speed at which pedestrians struck by drivers are significantly less likely to die than the state-set lower threshold of 25.

The bill was named for the son of one of those protesters, Amy Cohen, whose 12 year-old son, Sammy, had been killed by a speeding motorist a decade earlier.

“People ask, ‘Won't it be hard to not eat anything for a couple days?’" Cohen told reporters outside the Assembly chambers during her protest. "[But then I remember that] Sammy experienced so much pain because ... the car went right over his torso. If he can endure that pain and struggle for his life for five hours, and not make it, I can make a few days without food.”

Even Cohen's heartbreaking story — and the grueling 100 hours the protesters spent without food — weren't enough to move lawmakers to pass the bill that session, though a version with carveouts for arterials was eventually included in the state budget.

A new program, though, could soon help cities across America pass similar legislation without forcing bereaved mothers to starve themselves just to call attention to the issue — and possibly, leave fewer families to grieve in the first place.

As part of its new Cities Idea Exchange program, Bloomberg Philanthropies has pledged to help city leaders around the world pilot "sensible speed limit legislation," which the group says should adhere as closely as possible to the World Health Organization recommendation of 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) per hour — at least in the kind of dense, urban areas where a lot of people walk and roll. The program promises to connect interested cities to grant opportunities, technical assistance, "idea tours" of communities that have successfully slowed cars down, and a host of other resources aimed at making sure speed limits not only go down, but are actually reinforced by the kind of bespoke infrastructure, enforcement, and messaging strategies that will work in unique communities.

That effort is just one plank in a larger program aimed at helping cities adopt eleven proven solutions to some of the most commonly-reported civic problems, including street homelessness, air pollution, student learning loss and more. Rampant road deaths, though, might be among most prevalent challenges of all — and their root causes are among the most politically difficult to tackle.

“Whether you're in the United States or in sub-Saharan Africa or in Asia, we know that there are about 1.19 million people killed every single year in traffic crashes," said Kelly Larson, who leads Bloomberg Philanthropies' injury prevention work. "It's the leading cause of death for 5 to 29-year-olds. And that’s really just a shame, because those numbers don't need to be happening. Our goal is zero, and we know what to do.”

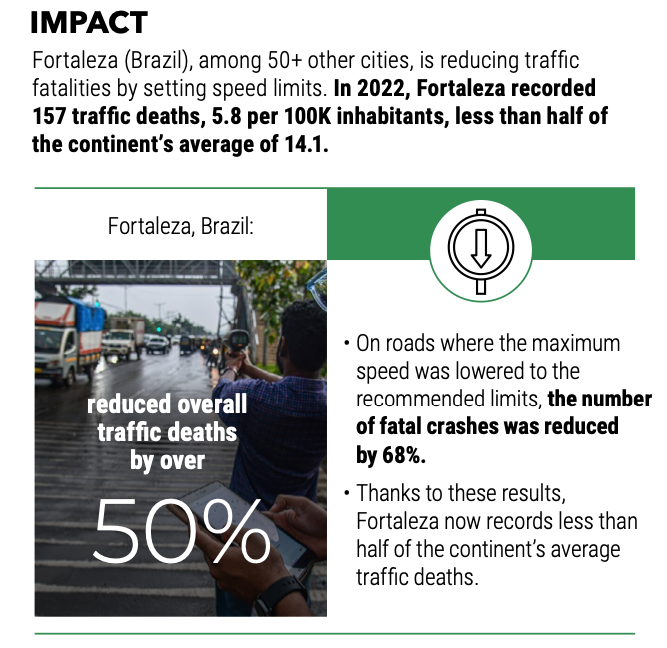

There's already evidence that the group is putting that goal is within reach. Even prior to launching the Idea Exchange, Bloomberg Philanthropies has been helping more than 50 cities around the world tackle their road safety challenges, and they estimate that their interventions will have saved nearly 312,000 lives by 2030. In Fortaleza, Brazil, lowering speed limits to WHO recommended levels helped cut fatal crashes by an astonishing 68 percent on impacted roads, and helped lower the overall death rate in the city to less than half of the average reported for South America on the whole.

Those results, the organization says, have everything to do with how the speed limit drops were handled — and the mentorship that cities received from experts as they went through the process.

“It’s not just about putting numbers on signs; it’s not even just about policy change," said James Anderson, who leads the group's Government Innovation programs. "It’s about how these new laws are implemented, about education around new expectations and enforcement. ... Not only do solutions have to be responsive to urgent challenges across different geographies, there’s a lot of hard work that has to happen when you adapt them to local circumstances and then implement them. And because there are so many challenges, were realized we needed to do something more.”

The Bloomberg Philanthropies team acknowledges, though, that most of its road safety work so far has been done in low- to middle-income countries — and lowering speed limits in the U.S. might be a steeper hill to climb.

Unlike some small nations that set speed limits at the national level, America operates based on a patchwork of state-level laws that are generally based on what's deemed "safe" for each roadway class, whether it's a limited-access highway or a sleepy residential cul-de-sac.

Those "safe" speeds, though, vary wildly from state to state, and they don't always reference the harsh reality of how likely pedestrians are to survive if they're struck at various velocities — or even how many pedestrians are actually around. And within each state there are a universe of carveouts that allow drivers to go faster on select roads, like the single state tollway in Texas where it's deemed "safe" to travel a blistering 85 miles per hour, despite the fact that at least 37 people died on that road between 2012 and 2019.

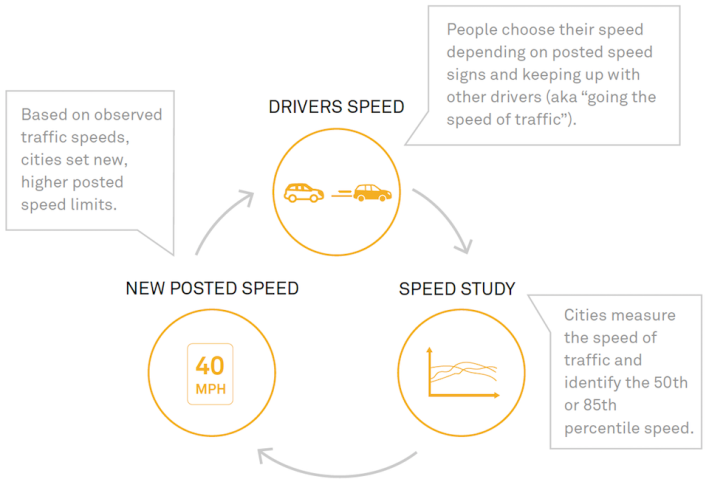

When traffic engineers are given discretion to set speed limits that are different than statewide norms, they've historically referred to the notorious 85th percentile rule, which essentially instructed them to record the speed of 85th-fastest driver on the road, then round that number to the nearest five mile per hour increment in order to determine the local limit. If that driver was hitting a velocity that could instantly kill a pedestrian, though, engineers weren't instructed to adjust the speed limit down — a method which NACTO says increased overall speeds over time, because it "forces engineers to adjust speed limits to match observed driver behavior instead of bringing driver behavior in line with safety goals and the law."

The 85th percentile rule was officially replaced in the latest edition of America's traffic sign design manual, the MUTCD, which was released late last year. But few communities have taken steps to lower their limits since — never mind implementing the kind of complementary infrastructure, enforcement, and messaging policies that would encourage drivers to actually obey them.

That's at least partially because of the political challenges of slowing down drivers — and the disturbingly common perception that fast speeds just aren't a big deal. A 2023 AAA study, for instance, found that roughly 40 percent of Americans did not think that doing more than 10 miles per hour over a residential area speed limit was "very" or "extremely" dangerous, and about a third admitted to hitting those speeds in the last 30 days.

The new Bloomberg Philanthropies initiative, in theory, could help U.S. cities wade into that thicket, first by simply connecting local leaders who understand the importance of taming their traffic speeds and showing them they're not alone. In addition to sharing strategies with their peers, localities in the Idea Exchange program can access training, toolkits and guides developed with other city leaders who have effectively slowed down drivers, as well as access to technical assistance, grant opportunities, and coaching on how to navigate any challenges they may confront.

“It could look like providing technical guidance on infrastructure; it could look like supporting the mayor in messaging about why they want to change speed in their respective jurisdiction," added Larson. "There's a whole host of offerings based on what the unique needs of the city.”

The first step, though, may be the most difficult of all for local leaders in a car-centric country: simply showing up and announcing their support for slower speeds.

"Since 2007, we've wanted to work with cities that raise their hand and say, 'Yes, we’re committed to doing this,'" added Larson. "So for those U.S. cities or international cities that are interested in addressing speed, sign up for this Idea Exchange and put your hat in the ring."

Learn more and sign up for the Bloomberg Cities Idea Exchange today.

Editor's note: an earlier version of this article misstated Kelly Larson's last name.