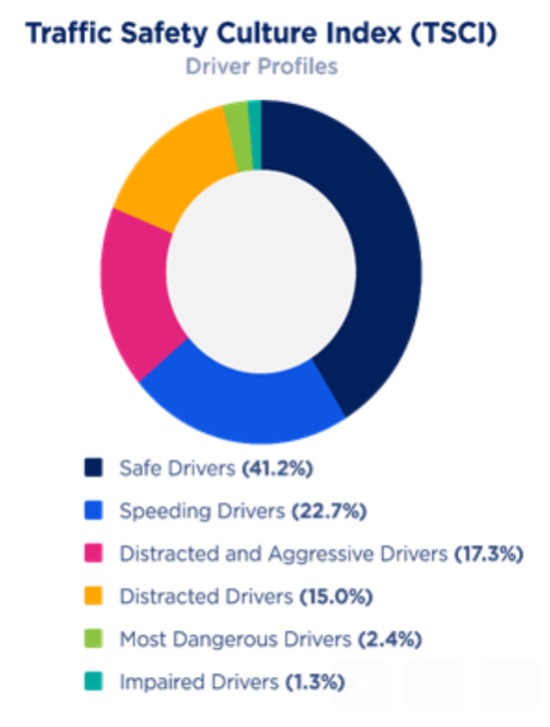

A disturbing percentage of U.S. drivers don't believe speeding is all that dangerous, a new study finds — and until America's safety culture changes, it may be hard to develop political support for the structural solutions we need to slow them down.

According to an anonymous survey of 2,500 motorists conducted by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, only 46.5 percent of U.S. drivers consider going more than 15 miles per hour over the speed limit on the freeway to be "extremely" or "very" dangerous — with 40.6 percent openly admitting to doing it at least "a few times" in the last 30 days.

In residential areas, meanwhile, only 60.5 percent considered exceeding the speed limit by 10 miles per hour to be especially deadly, with 27.7 percent acknowledging they'd done so more than once in the prior month. And because those numbers are self-reported by drivers, researchers say the reality is likely even worse.

"Speeding really is the standout behavior," said Rebecca Steinbach, senior researcher for AAA and the lead author of the report. "A lot of folks are not recognizing that it’s dangerous — and even if they do, a lot of them are doing it anyway."

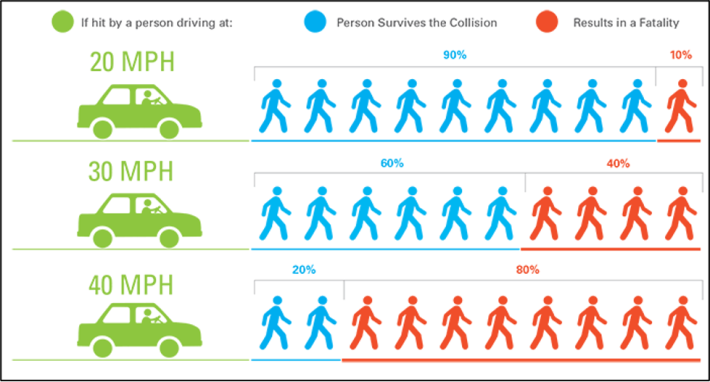

Those numbers may be shocking to anyone familiar with the decades of research into the relationship between high vehicle speeds and low crash survival rates. A pedestrian who's struck at the 25 mile per hour — a speed limit common in most U.S. neighborhoods — is more than twice as likely to survive than a pedestrian struck 35 miles per hour.

And while Steinbach is hesitant to say why, exactly, so many Americans are clueless about how deadly fast driving is — or why so many who do know choose to "do it anyway" — street safety advocates will find it pretty easy to speculate.

The unfortunate truth is, pretty much everything about U.S. transportation culture sends motorists the message that brain-melting velocities are completely banal, from the width of our driving lanes that subtly encourage us to hit the gas to the car commercials on our televisions that glorify going from zero to 60 in seconds. Meanwhile, decades of federal policies have encouraged road designers to set speed limits based on how fast motorists instinctually travel, rather than how likely those speeds are to kill, while awarding transportation agencies points on grant applications for cutting "delay" times and declining to fault them when speed-related death totals climb. Even common-sense policies to use technology to physically throttle vehicles below local limits have been met with fierce opposition, even when those vehicles are multi-ton big-rigs.

And while we wouldn't need to convince motorists that speeding was bad if we just lowered limits to logical levels and put traffic-calming infrastructure everywhere, Steinbach worries that's not likely to happen anytime soon.

"We can stop speeding at particular locations with environmental solutions like speed humps," added Steinbach. "But unless attitudes change, we're never going to stop speeding everywhere [else.]"

AAA acknowledges that education and cultural change alone won't end America's speeding epidemic — because it hasn't exactly done so for our other roadway epidemics, either. For instance, 93 percent of drivers ranked writing a text or email behind the wheel as "extremely" or "very" dangerous, but 27.1 percent said they'd done it in the last month anyway.

Those sort of dangerous attitudes, though, might be putting non-education-based safety solutions out of reach, too. A majority of the surveyed drivers (56.9 percent) said they "strongly" or "somewhat" opposed "using cameras to automatically ticket drivers who drive more than 10 mph over speed limit on residential streets" — which makes a kind of sense if they believe it's victimless crime, not to mention other valid critiques of certain camera programs.

To be fair, motorists aren't always willing to take action to prevent even the most heavily-stigmatized roadway behaviors, either. A stunning 31.3 percent of drivers on either strongly or slightly opposed "requiring all new cars to have a built-in technology that won't let the car start if the driver's alcohol level is over the legal limit," despite the fact that 94.4 percent of them recognized the deadliness of DUI. And even as drunk-driving has become less and less socially acceptable ever year, federal fatality statistics show that alcohol-impaired crashes have stubbornly constituted about a third of all road deaths since the mid-90s.

Still, Steinbach argues that despite those troubling numbers, American can't afford to leave any safety solution on the table — and that includes anything we can do to make it clear that speed kills.

"We have to do everything we can," she said. "We can’t discard any avenues of potential change. Structural solutions are important, vehicle solutions are important, but so is changing hearts and minds."