State departments of transportation across America face disturbingly little public transparency or accountability for how they spend our tax dollars — and as a result, we're often getting more highway expansions and fewer local projects that could give Americans the real mobility choices they deserve, a new analysis finds.

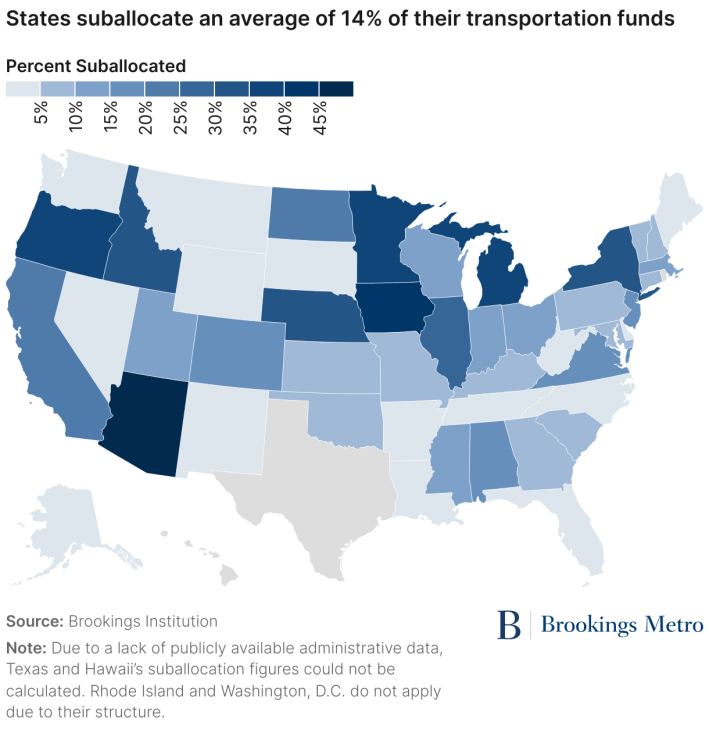

In a wonky but critical new study of all 50 state DOTs, researchers at the Brookings Institution found that states only give an average of 14 percent of their federal formula funding back to municipalities to spend on local projects, even though "the share of gas taxes states collect on locally owned roads tends to far exceed the share of revenues sent back to those local owners." The agencies at 15 states, meanwhile, sent less than 5 percent of that money back to municipalities — and the public often has little knowledge of how the rest of the money was spent.

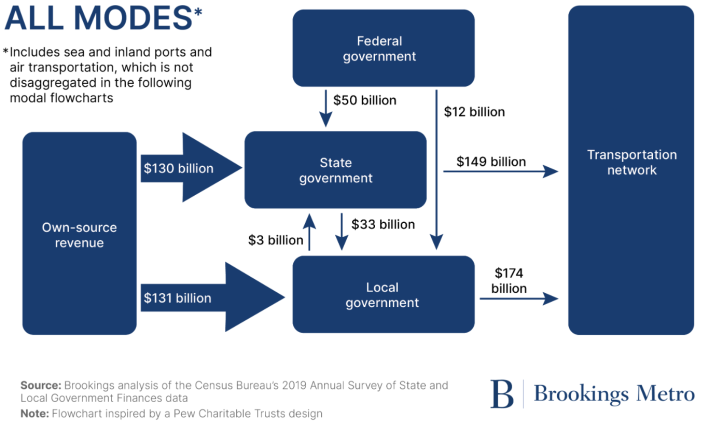

While the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act dramatically expanded cities' ability to apply for competitive federal grants directly, the majority of surface transportation money flowing out of Washington still comes in the form of "formula" dollars that guarantee state DOTs cash based on a set government calculation — and still gives state officials significant latitude over how that money is spent.

"We're kind of waving our arms and yelling, 'Hey, everyone — 75 percent of the IIJA is still committed directly through formula funds, including the grants that go to transit agencies," said Adie Tomer, senior fellow at Brookings and the lead author of the report. "And the bulk of those funds are going to states, not municipalities. ... So we're just saying, 'Wait, hold on; how do states choose what projects to build? What are we actually doing with all this money?'"

Why DOTs don't bother to grade their own homework — much less tell the public when they flunk

Of course, states don't have totally free rein over how they spend their formula dollars. By law, every state DOT has to submit a "Long Range Transportation Plan," to the federal government, outlining its transportation goals and planned investments over the next 20 to 30 years — and that document is supposed to align with national priorities like "increasing the safety of motorized and non-motorized road users" and "protecting and enhancing the environment."

Just because a state has those kinds of lofty goals, though, doesn't mean they're actually going to do the work to achieve them — or even measure how far off the mark they're landing year after year.

While 80 percent of the Long Range Transportation Plans that the researchers studied actually exceeded federal requirements, the analysis found that only 18 percent associated any kind of real performance measures with all of their goals — and 63 percent only did so partially.

So while a state may be publicly "committed" to, say, achieving net zero by 2050, it might not actually measure how many megatons of carbon its transportation system is actually producing every year. That could help explain why so many states sued to stop a federal sunshine law that would have required them to simply track their transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions, without even requiring them to reduce their annual pollution.

Meanwhile, only 20 percent of the agencies that bothered to set benchmarks actually released all of that data to the public; 65 percent only released some.

That's a little like a student promising to teach herself algebra instead of going to class, not bothering to take most of the tests in the textbook, refusing to share the failing grades she does receive with a teacher who might help, and giving herself an A+ at the end of the semester.

"If the goals themselves don't have targets, how can we hold the agencies accountable?" Tomer added. "And how can we ever expect the actual engineers, the regional divisions of DOTs, and the overall agencies to build projects that will advance those goals?"

Tomer and his colleagues argue that state DOTs or the governors who oversee them should require transportation agencies to "ensure every goal within their LRTP includes targeted implementation strategies and published performance measures."

In other words: fewer vague, toothless, goals, more proof that they're actually making progress — or not.

Fuzzy plans lead to bad projects

Even a state with a stellar Long Range Transportation Plan, though, might not actually be building great infrastructure projects that support its goals — and that has everything to do with how it selects what goes in the all-important Statewide Transportation Improvement Program.

The STIP, as it's colloquially known, is a critical document that drills down into exactly how state transportation agencies will invest their money over the next five years to support the goals and achieve any benchmarks outlined in their Long Range Transportation Plan. How exactly states are required to do that, though, is a little fuzzy in the federal code, and a lot of DOTs don't even bother to connect how a given project on that all-important list — say, widening an arterial in a neighborhood — is supposed to support the goals in their Long Range Transportation Plans — say, saving pedestrians' lives.

In practice, the researchers say 45 percent of states show no "demonstrable connection between their Long Range Transportation Plan and STIP"— and only 35 percent have any kind of a scorecard where they show the public exactly why they selected and prioritized each project they'll tackle in the near future.

"There is no question that the lack of performance targets — and targets informing project selection — creates a functional schism between what the planners intend, and the actual assets or projects that those dollars deliver," Tomer added. "And there's no question that this setup allows states to focus ... on roadway projects specifically, and even more specifically, on fast-moving, wide-lane highways."

Tomer argues that Congress should require every state to implement a "a public-facing project scoring system, using quantitative data that reflects the LRTP’s goals" — something states like Virginia and Kentucky already do. And if Washington won't make them do it, DOTs should take on that responsibility themselves, rather than wasting taxpayer money on projects that harm their communities.

Locals get left out

The report authors argue that state DOTs are also harming communities in another significant way, too: by not giving them enough of a say over which state-lead projects get built within their borders.

Under federal law, states are supposed to develop their long range transportation plans "in cooperation" with their local metropolitan planning organizations, but they aren't required to make sure those plans sync up with the MPOs' own blueprints for what they want to build in the next few years. And in multiple cases, the researchers say "state DOTs forced MPOs to update their long-range plans so the state could develop a capital project that was not in original alignment with those plans."

Put another way: if a state wants to bulldoze a highway straight through the proposed route for a city transit line, the city might be out of luck.

Shockingly, that power imbalance holds true even when locally-owned roads generate more gas tax dollars than state-owned ones — which they generally tend to do. Those taxes, of course, are then sent to Washington, which hands most of them back to states in the form of federal formula grants – and the states don't always pass that cash back to the locals that generated them, never mind the general taxpayers who have been subsidizing the highway trust fund for decades whether or not they drive.

"This is the single most important finding in the whole report, in some ways, because it brings it all down to actual practice," said Tomer. "We've got about 30 percent of revenues created on local streets, and then states are only giving half of that back to the locals to pick their own projects. The states are holding onto far more money than they should. ... It is, by our count, roughly double the amount that they should be keeping."

Of course, there are a few states that have bucked that trend, including Minnesota, Oregon, Michigan, Iowa, and Arizona, all of which pass down at least 35 percent of transportation dollars to their municipalities to spend as they wish. The report argues that other states should follow their lead, because "when a state financially supports its local partners, it is supporting a more balanced investment across local- and state-maintained roads in all areas of the state."

And it also argues that more often, Congress should skip the states entirely and "increase direct formula funding to regional governments" — a proposition that could be popular with conservatives and liberals alike.

"[We could deliver] a grand bargain where localities get a greater voice in what the projects get built — but states can actually focus on delivering the projects that people actually want," added Tomer.

Shining a light and building oversight

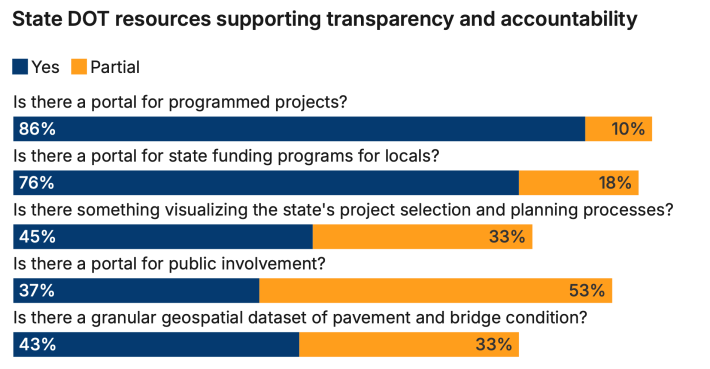

To a layperson, of course, all of these government procedures and acronyms can feel pretty wonky — even if she cares deeply about where her transportation dollars are going. That's why the report authors say it's critical that states do a better job of making their plans transparent to the public, while simultaneously building more formal oversight mechanisms to keep themselves in check.

And they've got a long way to go. While 86 percent of states had some kind of "portal" that outlined all of their planned projects, many didn't have an easy way for the public to get involved or learn more about why this highway expansion was prioritized over that road diet — never mind push back if they didn't agree with the decision.

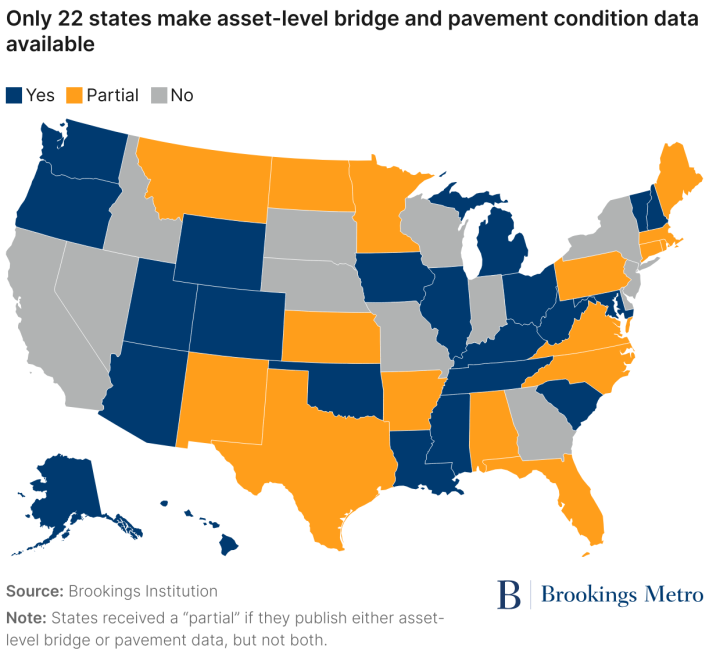

Meanwhile, only twenty-two states even bothered to report on the basic condition of their pavements and bridges — making it hard for advocates to argue that states should fix the roads they already have before they expand any more.

Even if they don't welcome input from an informed general public, though, most states do look to a dedicated advisory board to guide the development of their transportation plans — though the researchers argue that "many states are not tapping the full potential" of these boards to rein in bad projects.

If Congress deepened those relationships, the report authors argue that DOTs could still enjoy flexibility to "determine what priorities a commission will review" while still providing a much-needed check on wasteful projects and plans. And if they did a better job of bringing the public into the planning process, too, they could "build public trust and enhance DOT staff’s understanding of what communities want."

In a deeply divided nation, rebuilding that public trust may be more important now than ever — and transportation transparency could be a powerful tool to engage people of all political beliefs.

"Both Republicans and Democrats at a federal and state level are trying to earn the public's vote through asking for greater government accountability," Tomer added." What this report shows are ways to actually deliver that accountability. And we can deliver accountability while actually making government more efficient at the same time."