Transit agencies across America have 90 days to answer three urgent questions facing their systems today: how likely their workers are to be assaulted on the job, what they're doing to stop it, and whether those efforts are making a difference or creating new dangers.

On Wednesday, the Federal Transit Administration announced a first-ever general directive that will require more than 700 U.S. transit agencies to conduct a "risk assessment" on its transit vehicles and stations, and to issue a detailed, "data-driven" report on how they're monitoring and mitigating those risks. Virtually every U.S. city with more than 200,000 residents will be affected, and they'll have just under three months to complete their reports.

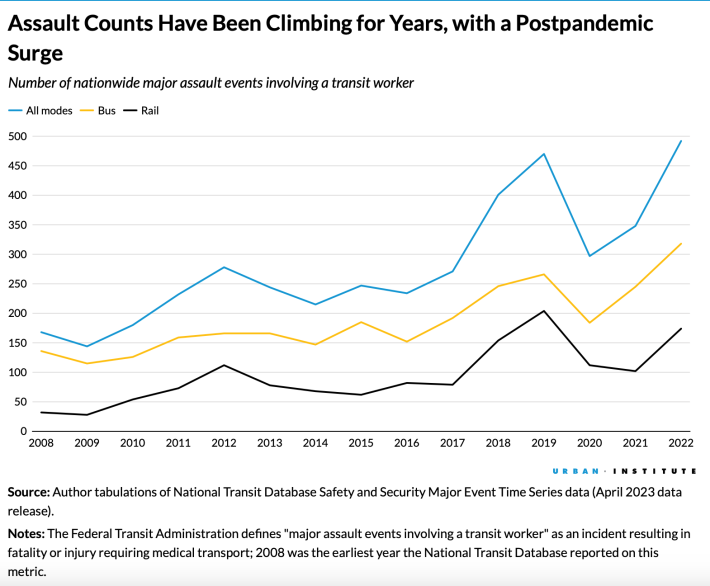

That mandate, coincidentally, came down on the same morning that a Los Angeles gunman hijacked a city bus, killing one passenger before being brought to a stop by a spike strip. Federal officials, though, stressed that violence against transit professionals is an unacceptable daily reality even when dramatic police chases aren't making the news, with physical assaults alone surging 120 percent between 2013 and 2021.

Attacks that killed or injured a worker, meanwhile, roughly doubled over the same period.

"Perhaps this tragic incident [in Los Angeles] underscores part of why we are making an announcement today," said US DOT Deputy Secretary Polly Trottenberg. "These are the men and women who get millions of Americans to work, to the doctor, to school, to visit family and friends every day. They're the ones who support our economies and quality of life in their communities. And I think all of us at DOT and FTA agree that it's unacceptable that so many of them fear for their safety, or even their lives, [when they’re] just going to work."

Some experts say that the safety crisis that the new DOT directive seeks to address may just be the tip of the iceberg — and that it has wide-reaching ramifications for riders, too.

Until a new provision in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law went into effect just a few months ago, transit agencies weren't even required to report certain assaults that didn't lead to serious injuries, including incidents of spitting, verbal attacks and hate speech, or drivers being pelted with objects and beverages.

When combined with the very real danger of physical harm, those kinds of indignities can easily push good transit workers to their limit — and eventually, out of the field. The rise in assaults against operators was cited by Transit Center as one of the four key factors driving America's bus driver shortage, which has forced many agencies to cut service.

And as service gets worse, agencies lose riders and fares, leaving them even less money to intervene to stop those attacks and accelerating a vicious cycle.

The kinds of interventions agencies do take, though, can often proven controversial — and sometimes, they carry dangers of their own.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, for instance, outraged advocates this June for her decision to deploy the National Guard and increase the presence of armed police on New York City subways to protect workers and passengers alike — a move which many feared would result in other forms of harm, particularly to BIPOC and unhoused communities who are disproportionately impacted by police violence, harassment, and profiling. New York City bus drivers unions, though, rallied for similar armed enforcement on their vehicles after a string of assaults on their drivers, including one incident in which an operator was stabbed in the neck.

While the governor credited the enforcement push with decreasing overall transit crime as much as 44 percent year over year, anger boiled over earlier this month when subway police shot four people while pursuing a suspected fare evader who had allegedly approached officers with a knife. The victims included two bystanders and one cop.

The new FTA directive might help agencies determine if strategies ostensibly intended to protect farebox revenues are actually endangering the lives of workers and passengers — and chart a better path to protecting them both.

"If there is an associated risk with enforcing fare payments, the transit agency needs to identify that and then discuss all the ways of mitigating that risk," said Veronica Vanterpool, FTA's deputy administrator. "So that is what we expect New York MTA to do as part of this — to look at other mechanisms and other strategies to deescalate a situation, but also to minimize the risk."

The directive could also help the FTA build a library of innovative safety strategies that comparable agencies could adapt from one another, and that the federal government could use to shape its own guidance and efforts to get Congress to devote more money to the issue. Some local agencies, for instance, have curbed assaults by installing clear plastic barriers between passengers and bus drivers, while others have had luck with unarmed "transit ambassadors" to help negotiate conflicts.

"What works for one system in a big city may not be [an] effective strategy in a tribal community," added Vanterpool. "So we're trying to gather this information and understand, so then it can inform some next steps that we take.”

Of course, the FTA directive won't create any new funding for agencies to beef up their worker protections — and it also won't address the societal inequities and civic unrest that some researchers say are the root cause of the problem. Still, federal officials argue that amassing more data on the transit worker assault crisis is the first step to solving it.

"Just as we're working to bring the deaths on American highways down to zero, we're focused on making certain no transit operator has to be afraid to go to work," added Trottenberg. "And no family should be worried that their loved ones are not going to come home safely each night.

An earlier version of this article mis-stated Deputy Administrator Vanterpool's title and first name. We regret the error.