Violent assaults on transit workers have tripled over the last 15 years — and researchers suspect the trend may be a symptom of broken social structures which transit agencies alone can't solve.

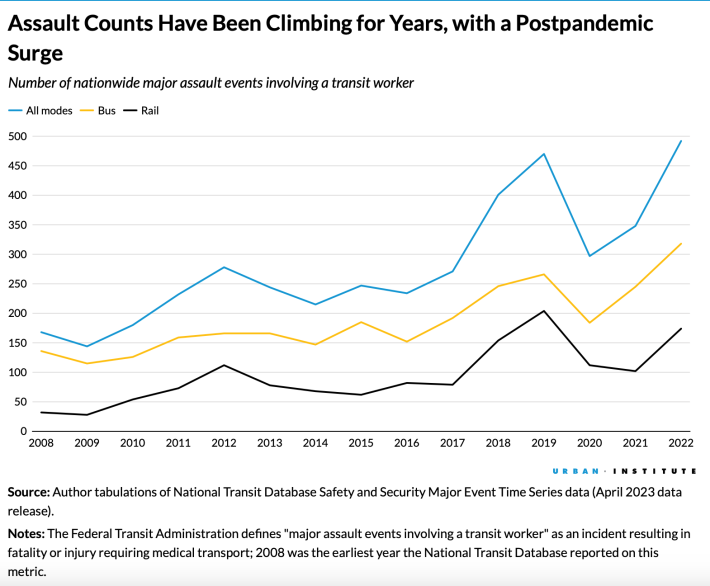

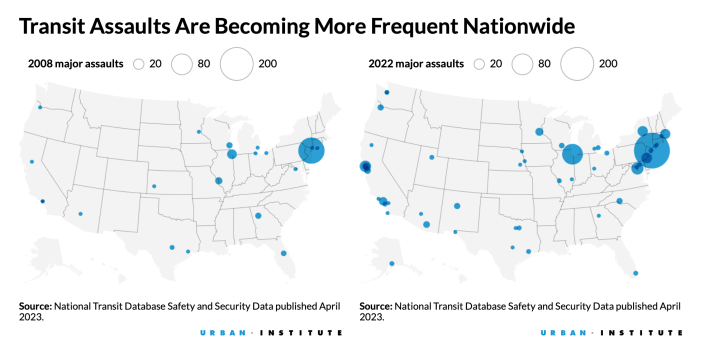

According to new research from the Urban Institute, America's transit workforce is experiencing an alarming increase in violent attacks, with incidents that resulted in a death or hospitalization climbing from 168 in 2008 to 492 in 2022.

And while agencies won't be federally required to report assaults that didn't result in a serious injury until the end of this year, there's reason to believe those are on the rise, too. In 2021, for instance, New Jersey alone reported 43 attacks that didn't require an ambulance for every one that did.

"That’s too large of an increase to let go quietly, especially for a problem that we have so much public data on," said Lindiwe Rennert, senior research associate for the Institute.

Rennert isn't the only one sounding the alarm about this crisis. A 2022 TransitCenter report cited workplace harassment and assault as one of the key factors driving the national bus operator shortage — which itself driving deep cuts to service nationwide. Those researchers also pointed out that on a per-trip basis, major assault rates against workers had actually quadrupled between 2009 and 2020.

Both reports said that agency-level solutions could help decrease those horrifying numbers, including physically separating drivers from passengers in clear-walled compartments, taking the burden of fare collection off of operators by enlisting ambassadors or eliminating fares entirely, and providing workers with de-escalation training to diffuse violent situations.

Rennert argues, though, that even those strategies don't really get at the root causes of why the workers that keep America moving are so frequently attacked — and what, exactly, prompts someone to lash out a train operator, bus driver, or even a worker cleaning the station. When she reviewed qualitative accounts of attacks, though, she noticed some troubling trends that could point to an answer, including verbal abuse and being pelted with objects.

"The use of racial slurs, things like throwing hot beverages and spitting — these are acts of malice more than acts of pure aggression or defense," she added. "There’s this undercurrent of distaste towards one another, of disconnectedness and social non-cohesion. It makes me wonder about our tendency to look at our fellow human being as an adversary, as opposed to as a compatriot. ... We’re products of our environments, and our environments are worrying."

Data may back up that hypothesis. Rennert found that rising assaults on transit workers in 2022 were positively correlated with increases in the "Gini Index" — a common measure of income inequality within a metropolitan region — and with the rising number of "riots, demonstrations, protests, and accounts of law enforcement violence against civilians."

Put another way: before disproportionately low-income and radically marginalized passengers even arrive at a bus or a train stop, they're carrying the weight of an unjust and violent society. And once they arrive, those indignities are often mirrored in the transit experience itself, including long waits at unsheltered stops with no seats, steep fares they can't afford, police violence if they're unable to pay, route maps, schedules, and services that weren't designed with their actual needs in mind, and a universe of other frustrations that can all too easily boil over.

"If you look at the space of the bus, it’s this tinder box of spatial competition and lack of control," Rennet added. "You have no control over the congestion you’re sitting in; maybe the stops aren’t being announced over the voiceover box because it’s broken; you may have to stand for long periods of time when you need a seat. ... [Transit workers are] a representation of larger institutions, and often, they’re one of the only ones we can engage with meaningfully. At a public meeting, we might feel like our reps are engaging with us only in a performative way. But on a bus, I am heard; I am felt."

Rennert says that improving service can be a "first step" to calming transit riders' frayed nerves, as can removing fares that often become a flashpoint for an assault.

She cautions, though, that any one of these moves alone won't solve the problem. Albuquerque, for instance, won a massive victory when it made its fare-free pilot permanent in November — but it also had the highest per-passenger rate of worker assault of any agency in the country during that pilot's first year.

"Albquerque may have removed fare payments, but it may still have low civic trust, a low sense of social cohesion, other factors that are feeding this violence," she adds. "There’s no silver bullet ... We see assaults across systems that have bus lane dedication, new vehicles, high quality service – they still have these issues. The transit agency’s ability to impact service alone will not zero out assault counts. But it is in agency’s best interest to protect their workers via the things they can control."

To really reckon with violence on shared transportation, Rennert hopes policymakers will think beyond the agency and explore more wide-reaching structural solutions to the rampant inequality that plagues riders, including automatically enrolling qualified residents in social safety net programs. And while the benefits of those policies might not spill over onto buses, trains and stations right away, they could have a radical impact over time.

"I want policymakers to realize that these acts of violence may just be how the public is lashing out from other inefficiencies, other ineptitudes, other dearths in our lives," she added. "And if our other needs are taken care of — including those that exist completely outside of transportation — then the likelihood of us lashing out may decrease."