Bus driver shortages are undermining transit agencies' efforts to recover from the pandemic and become the front-line mobility option that American cities need — and those shortages won't end until policymakers and transportation leaders confront the many structural reasons why so few Americans are climbing into the (bus) driver's seat, a new analysis argues.

According to a report from Transit Center released today, more than nine in 10 public transit agencies "are having difficulty hiring new employees ... and bus operator positions are the most difficult to fill." Moreover, those shortfalls are forcing a staggering 71 percent of providers to either cut or delay service, while others, like Los Angeles, are postponing service upgrades that would increase shared mobility access in the Black and brown neighborhoods that need it most.

That foundational challenge, though, has been relatively under-discussed in the debate about how to help transit agencies recover the riders they lost during the pandemic, even as journalists wonder why sky-high gas prices aren't tempting people onto shared modes. And that may be because the solutions auto the problem aren't as simple as just giving public transportation the robust funding it deserves.

Here are four reasons why it's so hard to hire and keep a bus driver on the payroll these days — and what to do about them.

1. Low starting pay, high retirement rates

Perhaps the most obvious factor driving the bus operator shortage is low pay — though Transit Center researchers emphasize that it wasn't always that way.

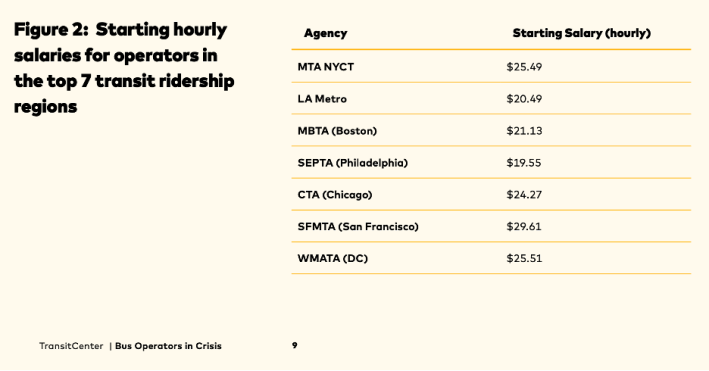

Back when baby boomers were first entering the workforce, becoming a bus driver was actually one of the fastest routes to the middle class for poor Americans, until costs of living skyrocketed, pensions were gutted, and the time it took to jump to the next pay grade swelled to as much as five years on the job. Today, an MTA driver in New York City can expect to make $25.49 an hour on her first day on the job, or about 40 percent less than the living wage for a single parent of one child in that region.

Unsurprisingly, those lucky boomers are some of the only ones who can afford to stay behind the wheel today — and they won't stay there for long. In 2021, the average transit worker was nearly 53 years old, more than 10 years older than the average American worker in other industries, and a staggering 72 percent of drivers who climbed behind the wheel just seven years ago are predicted to have either retired by the end of 2022, or switched to a better-paying job in another industry, like using their commercial driving license to operate a truck.

While securing new funding for agencies to up driver's pay and increase signing bonuses is an absolute must — particularly from federal agencies, which traditionally have offered mass transit little money for operations — the Transit Center team says it's just as critical for agencies to cut the costs of getting onto the job into the first place. Depending on the state, acquiring a commercial driver's license can cost thousands of dollars and take weeks or even months, and some agencies like the MTA in New York make their applicants wait six to 12 months just to be added to a hiring list.

Even if all those barriers are struck down, though, experts say many agencies still need to rethink how they communicate about the hiring process to applicants — and the benefits that await them when they jump through those hoops.

"Not everyone understands just how valuable it is to have a pension and affordable healthcare," said Chris Van Eyken, program manager for Transit Center and the author of the report. "The bus operator has traditionally been a really good way for working class, Black and brown folks to get a middle class job and advance in life. And as it degrades, it’s making it harder and harder for people to find ways to take a step up."

2. Workplace assault and constant indignity

Even the best compensation package in the world, though, may not be enough to recruit more bus drivers if they fear becoming the target on of violence on the job.

Federal Transit Administration data shows that between 2009 and 2020, physical assaults against operators increased fourfold per unlinked passenger trip — a stunning statistic that even transit agencies themselves have been slow to tackle, despite a new mandate from Congress to form safety planning committees in conjunction with operator unions.

"I knew it was bad, but the numbers [on a assault] were a lot more stark than I thought they would be," said Van Eyken. "Part of it is that there’s increasing financial stress on a lot of folks right now, and a lot of folks are struggling to pay the fare. When they come up short, the only person they have to take that out on is the operator, when probably, that anger should directed to the government at large."

Keeping operators safe without inviting potentially dangerous interactions between law enforcement and predominantly Black and brown passengers, though, will take serious investment.

Van Eyken points to the example of London, which physically separates drivers from passengers in transparent cockpits that still allow them to interact freely with their passengers — a model he says works particularly well in concert with improvements at stations to make bus stops comprehensively accessible to people with disabilities, without the driver needing to leave his seat to help them.

Other cities that have taken the potentially dangerous burden of fare collection off of operators by encouraging passengers to pay their share before they board; Seattle's Sound Transit is even piloting an unarmed "fare ambassador" program to help deal with on-board issues as they arise, rather than relying on a person piloting an advanced multi-ton machine to double as a social worker even while they're in motion.

And of course, no conversation about operator safety can afford to neglect the importance of protecting drivers from Covid-19, heat-related health conditions exacerbated by climate change, and other health hazards.

3. Punishing schedules

Being asked to perform the roles of a driver, social worker, ticket-taker, and guide to the city isn't the only reason why bus operators are prone to burnout. That's because too many agencies require them to work mandatory overtime and arduous split schedules to cover the morning and evening rush hours, leaving drivers little time to rest at home with their families in between.

"The way we build our schedules still assumes that the bus driver is male, and his wife is at home taking care of the kids and everything else around the house," added Van Eyken. "But it's a hard problem to solve, because at the end of the day, the schedule has to be fairly static and conform to what riders need."

Van Eyken says that the pandemic may already be helping solve the problem of split schedules, as transit commute patterns spread evenly throughout the day and agencies adjust their schedules to better serve all-day riders — something some advocates argue they should have done long ago.

When peak runs simply can't be avoided, though, he says agencies should offer operators higher pay for nights, weekends, and even the awkward few hours they have to kill between rush hour shifts, along with subsidized childcare and other caregiving services to lessen the burden, and digital services to help them find other operators willing to swap an inconvenient shift.

4. No respect (and no place to pee)

Perhaps the most important factor driving the bus driver shortage, though, is also hardest to tackle: the denigration of transit operators in American culture, including at transit agencies themselves. Though, again, the Transit Center team emphasizes that it wasn't always that way.

"If you go to the typical transit agency today, the older members of the leadership teams tend to be folks that started as operators and worked their way up," said Van Eyken. "The younger members, though, typically don’t have that field experience; they went to college and have a master's degree. They just don’t understand what it's like to drive a bus."

That stratification is no more apparent than in transit workers' access to the most basic workplace facilities. A stunning 80 percent of transit workers say that not enough time is built into their schedules for them to simply use the bathroom — if they can even find one, given the dearth of public restrooms in most US cities, particularly during the pandemic — and 67 percent report that they've experienced health problems as a consequence.

"If a white collar worker at the MTA didn’t have a place to go to the bathroom, the reaction would be, 'oh my god, that's horrible! We need to fix that!'" Van Eyken adds. "But that same thinking doesn’t apply to operators."

Van Eyken emphasizes that agencies must take systemic approaches to making drivers feel valued and heard, starting with strong pay, strong safety protections, and schedules that they and their families can sustain. (Mandated bathroom breaks and clean, guaranteed on-route facilities couldn't hurt, either.) And just as critically, they need to establish ongoing forums for agency officials to hear operator concerns, craft strategies to make their jobs better, and give them a path to rise through the ranks if they wish to.

"The end of COVID-19 will not bring the end of operator shortfalls; they will persist unless agencies address core issues with the job," Van Eyken wrote. To begin ending operator shortfalls, the transit industry as a whole must recognize the vital role that operators play and work to increase the attractiveness of the position. Transit operators are the backbone of the transit industry."