Sammie Hunter has been riding the bus in Memphis his whole life: as a teenager on the way to school, and these days, to work when his wife is using the single car that they share. It would take him about 20 minutes to drive to his job on an average day. But when he’s waiting for the bus, his commute can take over an hour – and that’s when the bus actually shows up.

“It makes it more frustrating when you have to stand out there and it’s hot,” he says. “The frequency isn’t great on these routes, but it didn’t used to be like this.”

Hunter is the co-chair of the Memphis Bus Riders Union, a local transit advocacy organization. For nearly 12 years, he’s been working with the group to push for better services for low-income riders, seniors, and those with disabilities who rely on public transportation to get around.

Over the years, he’s seen the transit authority struggle to serve residents of the sprawling, 324 square mile city, which is three and half times larger than Boston despite having nearly 30,000 fewer residents. Fixed bus routes are only punctual about two-thirds of the time; a popular vintage trolley line through downtown was recently shut down due to safety and budget issues.

“We deserve a better system,” Hunter says.

It didn’t come as much of a surprise to transportation advocates like Hunter when the Memphis Area Transit Authority recently approved a proposal to slash its budget by $17 million. The agency, which is $60 million in debt, will likely cut several bus routes and lay off nearly half of its 512 workers in 60 days.

The area’s bus network, meanwhile, will be reduced from 23 routes to just 16.

According to the agency’s most recent financial documents, MATA saw a $13.5 million decrease in revenue in 2023 from the prior fiscal year; its expenses, meanwhile, increased by $12.3 million, primarily due to labor costs. The agency’s debts are largely due to pension liabilities, a challenge they share with dozens of transit operators across the country.

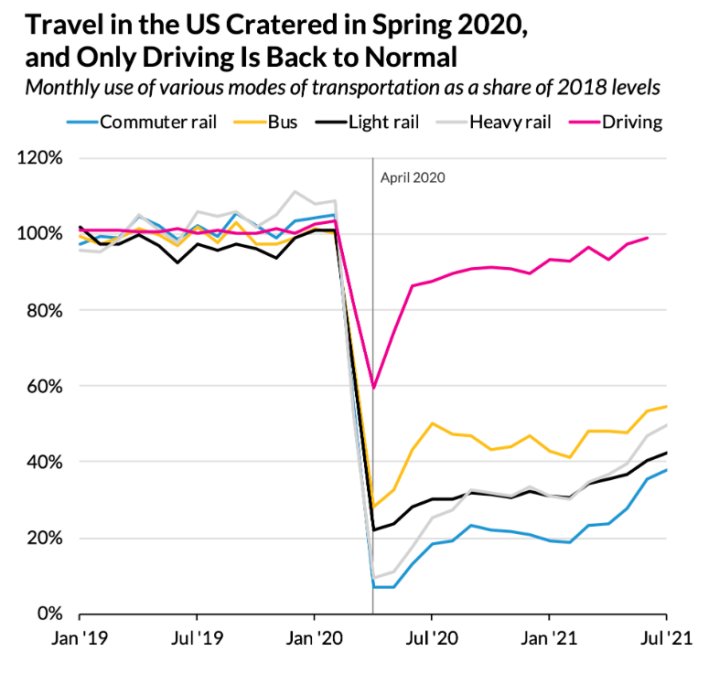

Ridership declines also played a role. In 2019, MATA reported an average of about 530,000 monthly bus riders; those numbers were cut nearly in half after the pandemic began, and like most U.S. transit agencies, they never recovered.

“We are committed to proposing a balanced budget,” the agency’s CEO, Bacarra Mauldin, told the Memphis City Council on August 20. “We recognize that these are radical changes, but you all are expecting radical results,” she said. “It’s not pretty, it’s not something we’re happy about…but we take our fiscal responsibility seriously as well,” she said, as people in the audience held up signs protesting the cuts.

Council members didn’t hide their frustration with the agency, which receives local funding as well as state and federal grants. One councilwoman went so far as to rip up the budget presentation after grilling Mauldin on the agency’s finances.

But Memphis isn’t the only U.S. transit agency facing declining ridership and revenues, and all the budget headaches that come with them. Even in large, transit-rich cities like New York or San Francisco, ridership has dipped since the pandemic began, as office workers haven’t returned to downtown hubs, says Brian Taylor, a professor of urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“If you look at who is riding transit, there are two markets,” Taylor says. “Downtown commuters, which had its legs cut out from under it during the pandemic, and people who have limited access to cars, who have been riding all along.”

Memphis received $35 million from the federal government to keep MATA afloat during the height of the pandemic — but by now, it’s all dried up. To Christina Stacy — a research associate at the Urban Institute who has analyzed how mid size cities like Memphis and Rochester used the funds to improve community services — that was a missed opportunity to shore up services with equity in mind.

“What we saw in many cities was that ridership was down, but the people who were most vulnerable to both COVID and inequities prior to [the pandemic] were the ones who had to continue taking public transit,” she says. “So they are really harmed by any reductions in transit.”

In the face of service reductions, many of America’s lower-income households also turned to car ownership, even among those who may struggle to afford car payments, insurance and other costs. And in large, car-centric cities like Memphis, Taylor says the sheer cost of running routes can hamstring public transit agencies, too.

“You might have the best transit manager in the world in [rural Texas], and an incompetent person in a city like San Francisco – and San Francisco will circle the block three times in terms of attracting riders, because the environment punishes you for trying to park a car,” he adds.

Despite its car-dependent landscape, 10 percent of Memphis households still didn’t own a car in 2020, and 40 percent, like Hunter, only have one car per household. For some, transit remains the only option, making the looming threat of bus routes being cut worrisome.

They didn't put the money in the right places. I know it didn't go to the buses and the bus routes."

Sammie Hunter, Memphis Bus Riders Union

Hunter says that, for years, advocates have been trying to engage with MATA to meet their needs.

“We gave them a plan, and they did not want to work with us on this,” he says. Requests for bus shelters, for example, or new buses to replace outdated ones, have never materialized. “We’ve been telling City Council to hold MATA accountable; they didn’t put the money in the right places. I know it didn’t go to the buses and the bus routes – it didn’t benefit the riders.”

MATA has announced a series of community engagement sessions as the agency moves forward, and in a statement, the agency told Streetsblog that it is committed to reducing impacts to seniors and those with disabilities.

“People have already voiced their opinions on this issue – how they feel when the bus doesn’t show up, and they’re waiting three hours,” says Hunter.

It remains to be seen how badly regular riders’ daily commutes and lives will be disrupted with the upcoming cuts. Some may need to rely on cashing in favors from friends or family for rides, or paying for Ubers – a luxury that not everyone can afford.

“What we hear anecdotally over and over again is that the more you invest, ridership increases and the better you do financially,” Stacy says. “So sometimes making cuts is the worst thing you can do. The buses come less frequently, and ridership goes down, you get less revenue … And that’s going to be a tough cycle to break.”