A new automated enforcement company hopes to end stop-sign running in America with the power of AI, inspired by its founder's personal brush tragedy on U.S. roads.

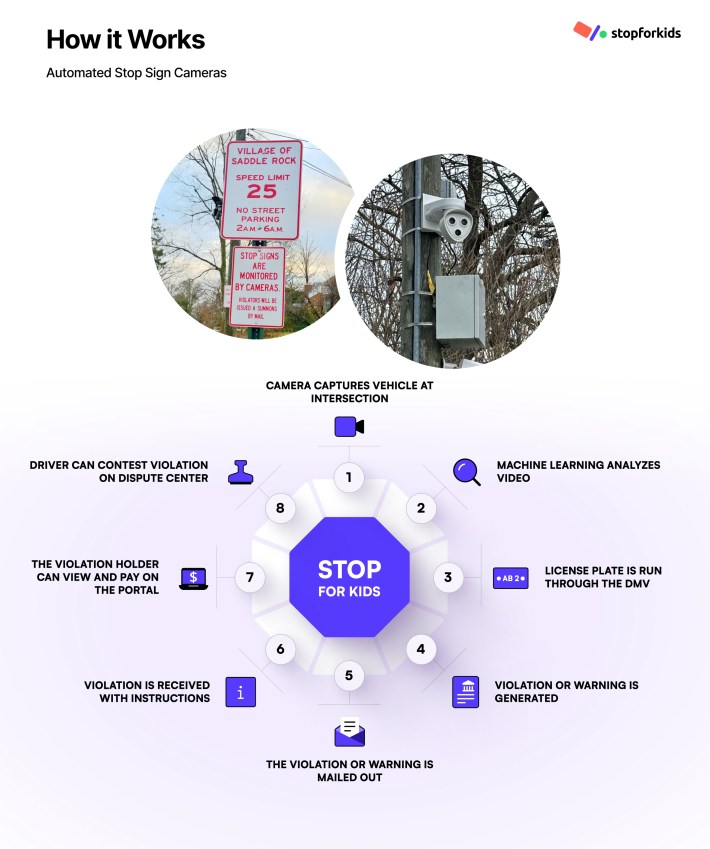

Last month, New York start-up Stop For Kids announced that it was expanding its "Road-Safety-as-a-Service" model to communities across America, allowing local governments to install the company's AI-equipped cameras on stop signs with high rates of running at no cost to them. The company will recoup its fee by taking a portion of driver's fines — though founder Kamran Barelli hopes the model won't make him rich.

"I pray for the day to come when we have to go out of business because everybody stops," Barelli said. "That will be our ultimate goal. I will be the first one to cheer if we have to take down the cameras because everyone stops [where they should]."

Kamran — along with his brother and co-founder Kiyan — are the first to acknowledge that goal won't be easy to achieve. According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, there are about 700,000 crashes at U.S. stop signs every year, and one-third of those crashes involve injuries.

Among those victims was Kamran's wife and children, who were struck in 2018 when a distracted driver ran a stop sign, plowing into the young mother as she pushed a stroller on a Long Island road without a sidewalk. Barelli's family survived — the couple's son, miraculously, was totally unharmed — but they were thrown "around 58 feet" and his wife had to re-learn how to walk, he said.

That horrifying incident made the Barelli family newly aware of just how many drivers in their community were endangering other road users at intersections — and how challenging it was to get them to stop. Emails from the municipality begging motorists to hit the brakes were largely ignored; when the city put up digital speed signs, they say teenagers competed to see who could race past them faster.

"The only thing that worked was if a police officer was hiding at the intersection and giving out citations," Kamran said. "Unfortunately, they can't be there 24/7 — and the fact is, within hours of them leaving the scene, everybody goes back on their WhatsApp and tells the community that the police are gone, so they continue driving right through the stop sign."

That didn't sit right with either of the Barelli brothers, who grew up in Zurich and had witnessed the power of that city's famously robust automated enforcement program firsthand. But while the Swiss hand out million dollar "day fines" to its highest-income speeders and snap photos of red-light runners every day, their adopted village of Saddle Rock had fewer tools at its disposal.

"Everyone [in Zurich] rides bicycles and uses public transportation; over the years, they've made some streets car-free," added Kiyan. "We come from that mentality of cars needing to slow down and drive safely, and having respect for pedestrians when they want to cross the street."

Both tech industry veterans, the Barellis decided to develop an AI-powered camera of their own that can be installed in under an hour and operate in all weather conditions. When they launched the prototype model in Saddle Rock two years ago, they say only three out of 100 cars would reliably stop at the line; within 90 days of the cameras being active, though, compliance jumped to 85 percent. Today, it's 95 percent, and neighbors have requested four more cameras throughout the area.

The brothers argue that success has to do with the accuracy of their product, which has a false positive rate of under .06 percent and can be adjusted to give leniency to drivers who might drift a few inches over the line or roll forward after two seconds instead of three. ("Frankly, nobody really does a perfect, by-the-books stop," Kamran laughed.) To preserve residents' privacy, faces, vehicle models, and even license plates are all anonymized and automatically deleted unless the AI detects an offense to be sent to the local DMV, and drivers who do break the law are sent a QR code to access video footage of their infraction along with their ticket.

Municipalities can also opt to give drivers' warnings for their first offenses while they learn that the cameras are watching, though both brothers say that municipalities don't need a camera on every corner to get motorists to hit the brakes throughout the community.

"We've seen that other stop signs are now being respected by drivers, even without monitoring. ... Our goal is not to penalize the driver or generate all these violations," added Kamran. "The idea is to give residential communities and school zones the tools they need to make their roads safer."

The Barellis hope these features will set their product apart from other stop-sign cameras on the market, which tend to rely on flash technology that can disturb nearby neighbors — and, they argue, generate less-accurate results. A single Washington D.C. camera, for instance, made headlines for raking in $1.3 million in two years, with some residents arguing they'd been ticketed even after making full, three-second stops.

Those types of inaccuracies can lead residents to see cameras as a craven money grab rather than a critical road safety tool, especially when cities and camera manufacturers use the money from violations to line their coffers when stop-sign violations surge undeterred. The Barellis argue their company's pricing structure and sheer success at curbing deadly behavior can help assuage those fears — and they point out that any fines that do get collected could be channeled into other prevention strategies, like infrastructure.

"Something has to be done," added Kamran. "People go through red lights, and there need to be consequences. But I believe it should be done in a way where you don't break somebody's wallet. The approach should be to bring awareness and improve driving behavior — [and it's] working."