Congress has launched an investigation into whether America's limited vehicle safety standards are driving the rise in deaths of vulnerable road users — and what it will take to finally stop automakers from selling cars that countless studies show are disproportionately likely to kill pedestrians, cyclists and other people outside vehicles.

That review by the Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress, was requested by Rep. Jamie Raskin (D–Md.), who noted that both pedestrian and cyclist deaths have recently reached record-highs and that the United States “an appalling exception among developed countries” that have far less bloodshed.

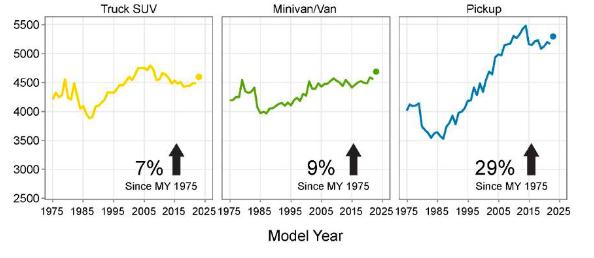

The ever-growing stain our national reputation is partially attributable to our ever-growing cars, trucks and SUVs, some experts argue. Between 1993 and 2023, the average vehicle on U.S. roads swelled by 1,000 pounds, while simultaneously getting four inches wider, 10 inches longer and eight inches taller — bloat that's driven by the increasing sales of pick-up trucks and SUVs.

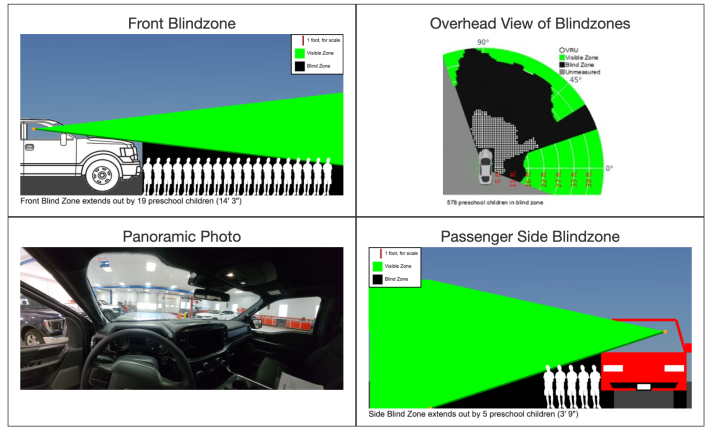

That’s enough to bring the hoods of America’s best-selling cars, like the Ford F-series pick-ups, up to chest level for many adults, all but guaranteeing crashes will cause damage to vital organs rather than the legs, where injuries are more survivable. The swelling size of the U.S. fleet has also increased the size of blind zones so much that drivers often can’t even see long lines of children right in front of them, and made it far more likely for pedestrians to be pulled under the wheels rather than pushed up onto the hood, where they’re less likely to be killed.

One study estimated that 18 percent of pedestrian deaths could be avoided just by capping the hood height of passenger trucks and SUVs at the level of a modest crossover.

“All the research shows that the design of cars and trucks — including their height, the geometry of the vehicle, and their weight — all come to effect the safety of vulnerable users on the road,” Raskin told Streetsblog. “As cars have gotten bigger, blind zones has gotten bigger, and that increases the chances that drivers may inadvertently strike and kill a pedestrian. … These are design problems, and we should get the best research available to [solve them].”

Raskin says his letter was inspired in part by losing his own cousin in a Florida crash, as well as the tragic death of his constituent, Sarah Debbink Langenkamp, a decorated diplomat who was killed while cycling home from her sons’ school in Bethesda in 2022. In the wake of her loss, lawmakers like Raskin fought to pass legislation bearing her name, including a bill Raskin introduced to help states get more federal money to complete protected bike lane networks, and a Maryland state bill to increase penalties on drivers who hit cyclists in bike lanes or shoulders.

“Family members who have lost loved ones through traffic collisions and injuries are a really important force for change,” Raskin added. “I want to salute the Langenkamps, and every family in this situation, who help to convert the nightmare tragedy of this kind of road violence into energy for positive change and reform.”

Despite that advocacy, though, vehicle safety regulations have remained a missing piece of the puzzle. Raskin noted that the vehicle that struck Sarah was a large flatbed trailer with huge blind spots — something neither National Highway Traffic Safety Administration nor the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration addresses — and it also wasn’t outfitted with pedestrian and cyclist-specific “side-underride” guards that could have prevented her from being swept under its wheels.

An explosive ProPublica and PBS Frontline documentary revealed last year that regulators were poised to mandate that equipment, but ultimately didn’t after trucking industry lobbyists took a red pen to their report and shank the number of people who die in underride crashes.

And when it comes to passenger vehicles, things aren’t much better. A provision in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, for instance, required federal regulators “to establish a means for providing to consumers information relating to pedestrian, bicyclist, or other vulnerable road user safety technologies” — but regulators chose to focus on assessing advanced pedestrian automatic emergency braking technology, rather than the far simpler and older “technology” of a shorter hood that won’t destroy a walker’s internal organs, or a narrower A-pillar that can shrink a massive blind spot.

Even worse, studies show those automatic emergency braking technologies don’t even reliably work at the high speeds and in the dark conditions where the vast majority of pedestrian deaths happen.

The GAO investigation promises to shine a light on all the other vehicle design features that experts say could impact the national traffic violence epidemic, including but not limited to “height, geometry, driver visibility and direct vision.” And Raskin has also requested that the agency take a look at what other countries have done to address the risks posed by poor design, as well as the challenges agencies and automakers might be faced with if they sought to mirror those solutions here.

Of course, the GAO can’t force anyone to tackle the megacar crisis — and Raskin himself points out that NHTSA has yet to implement the agency’s now four-year-old recommendation that it “decide whether to include pedestrian safety tests in [the New Car Assessment program].”

Still, by collecting the mountain of research about the safety risks of megacars and delivering it to Washington’s doorstep, Raskin hopes that it can prompt a conversation that leads to larger change.

“I think all of us need to incorporate and promote the idea that nobody should be killed on our highways and roadways,” he adds. “That should not be some acceptable cost of doing business.”