When states raise speed limits on highways, speed-related crash hot spots spike on nearby neighborhood roads, a new study finds — but local communities aren't preparing for those "spillover" effects, nevermind getting a say in how fast motorists should go on the interstates that rip through their communities.

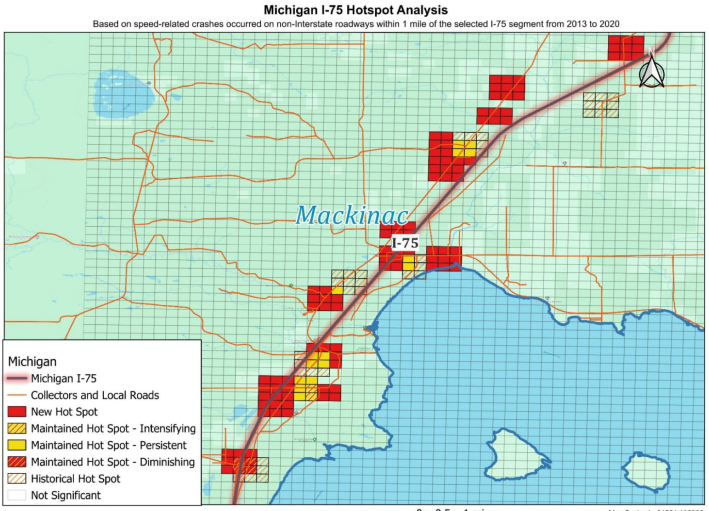

In an analysis of three U.S. highway segments whose maximum speeds were increased at some point in the last decade — I-85 in Georgia, I-84 in Oregon and I-75 and I-69 in Michigan — researchers found that all reported significant new "clusters" of speeding-related crashes within a one-mile radius of the interstate.

Worse, all three communities also reported that crashes had become more frequent at many of their old non-interstate crash hot spots, and that these "safety concerns" outweighed the handful of areas where crashes went down because of shifting traffic patterns and other factors. And of course, that's only accounting for collisions where police checked the box on the crash report to indicate that speeding was a factor, not the many other incidents where motorists collided at deadly but perfectly legal velocities.

Those findings complicate the common belief that rising interstate speeds have little impact on people who don't travel on those roads — including pedestrians and cyclists who aren't legally allowed to enter them at all, even if they're often forced to.

"When [states] raise the posted speed limit, they will typically tell you, 'Well, we can do a before-and-after fatality count to see if we see an increase' — and if they don’t see a significant increase, they draw the conclusion that there’s no negative safety impact," said Dr. C.Y. David Yang, president and executive director of the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, as well as the co-author of the study. "But what happened to those neighborhood streets along the interstate? How are they being impacted? … I think we are probably one of the few researchers during the past several decades that has been asking this question."

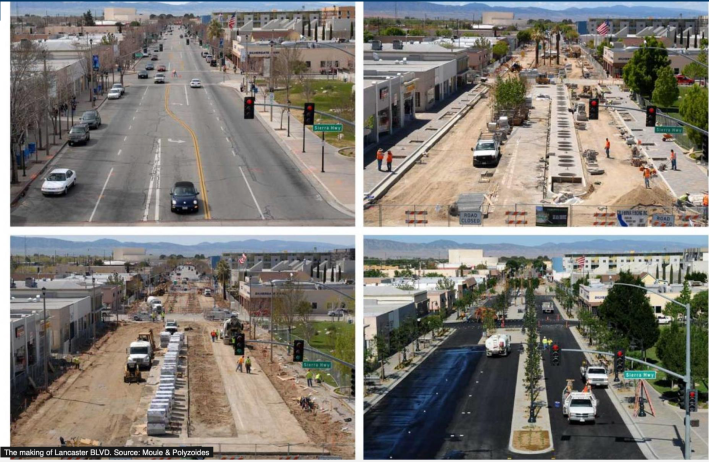

Yang hypothesizes that, similarly to the "distraction hangover" that drivers experience even after they stop using a cell phone behind the wheel, motorists don't immediately register just how quickly they need to slow down after they exit the interstate — especially when local roads themselves are designed like highways where it's perfectly fine to go fast. Countless studies have shown that interstate-style design features like multiple 12-foot lanes and wide shoulders encourage motorists to hit the gas, even when the road they're on is signed for lower speeds and shared with people on foot.

"It takes a moment for them to realize, 'Oh, I need to decelerate because I'm on a local street that doesn't that's not designed to accommodate 65 miles per hour, now,'" he adds. "'I'm in a community where there's children playing.'”

Even if highway-adjacent communities knew about "spillover" speeding effects, though, they might not be able to easily stop them.

Because interstate routes and their speed limits are typically set at the state level, local communities don't usually get much of a say in whether highways will run through their neighborhoods, or how fast motorists will travel on them when they do — and their local transportation leaders don't always take action to slow those motorists down when they exit the highway, either. That's particularly problematic around interstates like I-85, which is flanked by historically disadvantaged communities in metro Atlanta, including several suburbs.

While Yang stops short of saying that speed limits should never be raised on the highway, he says it's critical that stakeholders like state, county, and city departments of transportation communicate in advance of those increases, so the locals can take action to slow drivers down, like modifying road designs.

“[They need to be] in the discussion, so that a holistic solution can be proposed — instead of just saying, 'I'm just going to raise this speed limit, and hopefully, nothing will happen,'” he adds.

Some advocates might say that we also should have a meaningful conversation about whether highways belong anywhere near neighborhoods in the first place — and seize the historic opportunity we have as interstates reach the end of their useful lives to remove them before anyone else gets hurt.