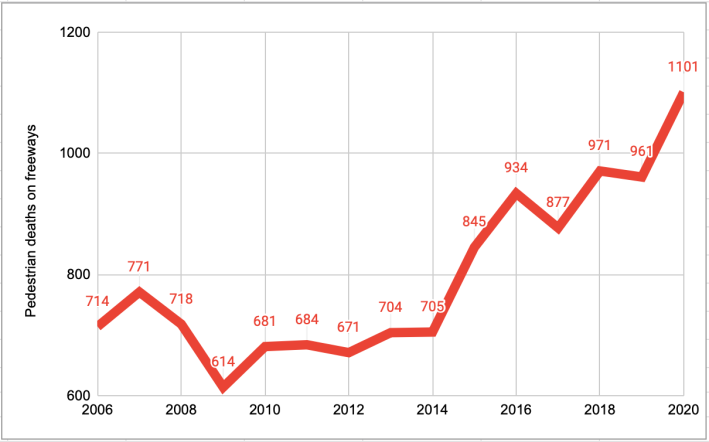

A surprising 17 percent of U.S. pedestrian deaths last year happened on roads where people theoretically should never be walking — and that troubling finding should prompt a conversation about why so many of them are doing it anyway.

As part of its recent analysis of 2021's stratospheric surge in walking deaths, the Governors Highway Safety Association flagged that nearly one-fifth of walkers who died on U.S. roads were actually on controlled-access freeways or interstates — roads which intentionally have no walking infrastructure, and which are explicitly designed to encourage vehicle speeds that are all but guaranteed to kill upon impact with an unprotected human body.

Offering no hard evidence, the Association posited that those 1,101 lost lives were "more likely to typically be stranded motorists who exit their vehicle, construction workers, first responders or tow truck drivers," rather than people traveling to their destinations on foot, which the group says suggests a stronger need for driver education and enforcement around "Move Over" laws that require drivers to slow down and give these road users more space.

Decades of analysis, though, shows that the vast majority of freeway pedestrian deaths were not motorists who recently exited their vehicles, but people who chose to — or had no choice but to — walk on or near roads with vehicles traveling at speeds that will kill a walker nearly 100 percent of the time.

And just like fatalities in other roadway environments, those deaths have increased nearly every year since 2009.

Contrary to the GHSA's hypothesis, a recent Insurance Institute for Highway Safety study found that just 18 percent of walkers killed on freeways between 2015 and 2017 were motorists whose vehicles had recently been disabled, and just 1 percent were road workers. Another 2 percent were noted to have been in the act of "entering or exiting a vehicle" of any type at the time they were killed, bringing the total share of "pedestrians" who died after recently being inside a car, truck or ambulance to just 21 percent. (A 1997 study pegged that number at 32 percent, which could indicate that more non-motorists are walking on freeways today.)

That's certainly a higher percentage of "unintended pedestrians" than die on other types of city roads, but it's a far cry from the staggering 42 percent of people who died while actively attempting to cross the fastest thoroughfares in the U.S. road network. Another 10 percent died while walking along freeway shoulders, while a further 6 percent were "standing, lying, playing or walking" in the driving lane — bringing the total share of walkers who died on a controlled-access highway that they had entered outside of a vehicle to a staggering 58 percent. (The remainder were listed as "other" or "unknown.")

The question of why so many pedestrians are walking on roads that weren't designed for them is hard to answer definitively, but experts say that their sheer prevalence of these deaths signals that they're not just a horrifying anomaly.

"We were shocked when we fist saw these numbers. But since we know highway speeds are essentially unsurvivable, maybe it shouldn't be so surprising," said Jessica Cicchino, IIHS's vice president of research and co-author of the study. "It really points to the fact that people trying to get across these high speed roads without having a better way of getting there, and that's something really need to deal with."

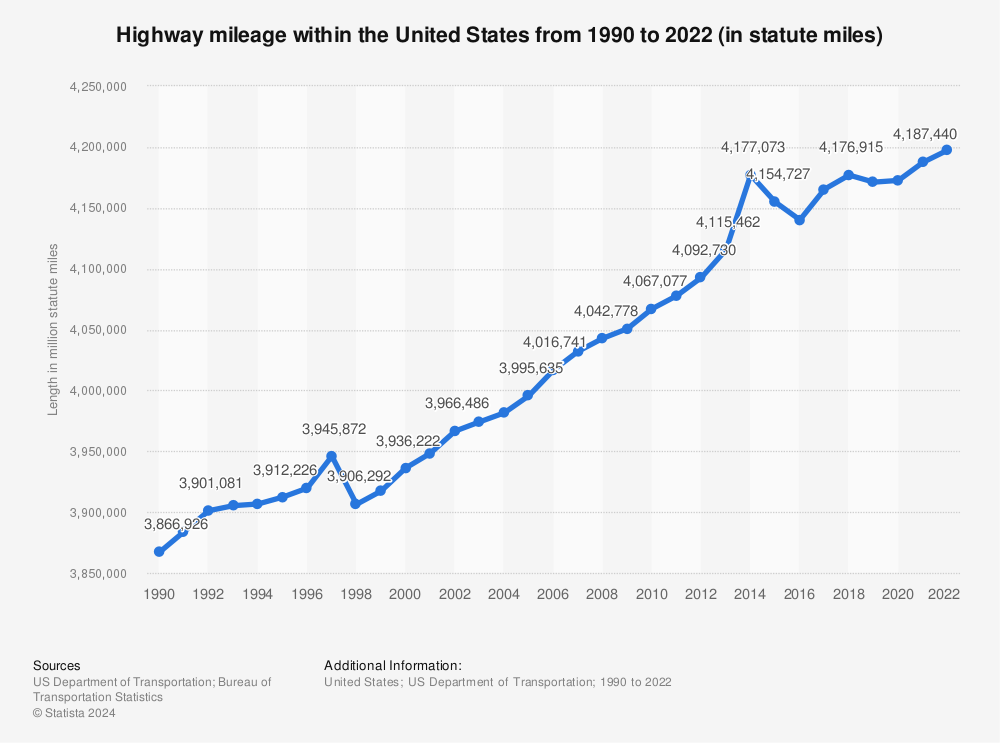

Graphic: Statista

Of course, the most obvious factor driving the interstate pedestrian death trend is the sheer prevalence of freeways in American cities, many of which were designed to deliberately divide Black, brown and low-income communities and cut millions of from the destinations upon which they relied.

And that racist and dangerous experiment never really stopped. Between 2009 and 2020, America has added about 120,000 new highway miles, often in the form of widening existing freeways and interstates — and for every new mile of asphalt, studies show that interstate pedestrian deaths increase, too.

That's part of why Cicchino says that, just like in every other roadway environment, walker-friendly infrastructure must be a frontline solution, at least in freeway-appropriate forms. That might look like installing pedestrian crossing bridges, overpasses, or underpasses at the site of frequent crashes, improving lighting along road shoulders to prevent the 48 percent of walking deaths that occur on unlit freeways after dark, or increasing access to transit so people on foot aren't tempted to brave a dash across an interstate in the first place.

And sometimes, it might look like getting freeways out of the cities altogether — or at the very least, capping over them, and building a network of more people-centered roads on top.

"I mean, if the highways weren't there, pedestrians certainly wouldn't die on them," Cicchino adds.

Of course, dangerous infrastructure decisions aren't the only factor driving the pedestrian death crisis on America's freeways.

Interstates, in particular, are explicitly designed around the needs of freight truck drivers, 40 percent of whose miles are logged on the nation's super-highways, compared to just 1.2 percent of total mileage for Americans on the whole. It's well documented that the taller and more aggressively designed the vehicle, the more certain a walker is to be killed when struck — and as non-commercial vehicles swell in size, too, and dominate more and more of the auto market, a pedestrian's chance of death on any U.S. road is climbing even higher, too.

Interestingly, controlled-access freeways are not the site of a disproportionate rate of dangerous motorist behaviors like drunk driving — rural highways are considered to be more deadly on that count. And while federal crash databases say a greater share of pedestrians who died on interstates were drunk when they were struck — 40 percent of them were reported as having a blood alcohol concentration of at least 0.08, vs. 32 percent of all dead walkers in other settings— as much as one-third of those assessments were based on "imputed BAC" as determined by the opinions of police officers, rather than actual, confirmed laboratory tests.

More to the point, though, walking while drunk is not a crime, and for good reason: because choosing to do it prevents drunk driving, which is far more dangerous for the traveler and everyone with whom they share the road. And rather than dismiss these deaths as the actions of a handful of reckless people who made poor choices while their judgment was impaired, Cicchino stresses that we must look to systemic solutions, like transit.

"The biggest solution that comes to mind is just giving people other ways to get to where they're going, so they don't have to be walking if they're impaired," she adds.

If American communities can finally do that, freeway pedestrian deaths could easily become a thing of the past — and if they can't, more people will die.

"Highway speeds and pedestrians are a lethal combination," Cicchino adds. "Continuing to build freeways that cut through neighborhoods where people live and where they want to go will increase the risk that walkers will cut through these roads that just weren't built for them — and that's going to have these kinds of deadly consequences."