America is at a watershed moment in the fight to heal the harms of urban freeways that tore apart predominantly BIPOC and low-income communities, a new report argues — but what that healing will look like, exactly, is still an open question.

The Congress for the New Urbanism’s latest Freeways Without Futures report identified 10 aging urban highway projects that are particularly prime candidates for conversion into boulevards.

CNU’s list — selected by a panel of experts every other year since 2008 — has become a powerful advocacy tool, with 18 of its nominated roads actually being demolished and replaced with human-scaled designs over the years.

This year's candidates are the first to be nominated at a time when the federal government is actually giving out money to U.S. communities — specifically to make their freeway-fighting dreams come true. Several highways on the list have already won federal grant money.

Half of this year's list received funding during the first round of the new Reconnecting Communities Program, which will provide $1 billion over five years to remediate the negative impacts of highway projects — and the report authors suspect the others are likely to apply for the upcoming Neighborhood Access and Equity Grants program, which will devote $3 billion to similar projects over the same period.

Both programs, like the CNU report itself, emphasize projects that will not induce residential displacement while maximizing benefits to legacy residents — and even communities that haven't yet won a grant say the programs have inspired them to explore better options for their transportation futures.

"Just the existence of this funding has really moved up the conversation in a lot of cities," said Lauren Mayer, CNU's communications manager and the lead author of the report.

"In Youngstown, for instance, they basically saw the Reconnecting Communities notice of funding, and it prompted them to start saying, 'Oh; we can actually start studying what it would take to remove this piece of burdensome infrastructure [known as Route 422].'"

Mayer is careful to note, though, that the new federal money won't necessarily be spent on freeway removals — at least not everywhere.

A local campaign in Minnesota's Twin Cities, for instance, recently won a federal grant to study the completion of a 0.5 mile-wide land bridge across Interstate 94 that some advocates hope will restore mobility and opportunity to the historically Black community of Rondo that was demolished to make way for the highway. The campaign that was nominated for the CNU list, however, argues that a full boulevard conversion of the outdated highway is possible, and would be an even more radical act of spatial justice.

"It's great that this community is trying to do something that they very much need… But why not do that for this whole 7.5 mile stretch of trenched highway — versus a small, half-mile stretch that would would be very good for one community, but then would shut other communities out?" Mayer asked.

Another controversial grantee on CNU's list is the city of Austin, Texas, which won funding to study the possibility of capping sections of Interstate 35 — without pausing an ongoing project to widen that same road. As in Rondo, some advocates have mounted passionate campaigns in favor of the federally-funded project, while others have fought for a more radical vision — in I-35's case, re-routing the highway away from downtown Violet Crown entirely.

Mayer suspects those sorts of tensions are unlikely to go away anytime soon. That's why it's more critical than ever that advocates keep pushing for true transformations rather than band-aids, she said. If they do, Mayor hopes the future of the Freeways Without Futures report will soon look very different.

"My biggest hope of all, of course, would be that all the freeways are torn down in cities, so we don't have to even be harping on this," she joked. "But really, the dream of this report going forward is that it becomes less about trying to fight these expansions that are still happening, and becomes more about showcasing all the different approaches that the community can take to make freeway-fighting —and freeway removal — a reality."

Here are the other seven selections for this year's Freeways without Futures list, which Mayer emphasizes is non-exhaustive:

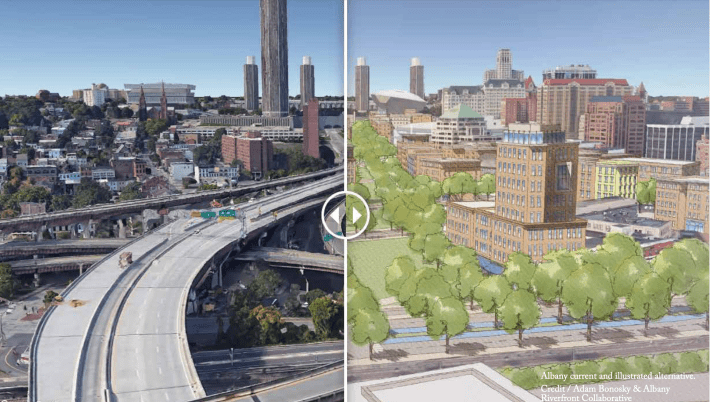

- Albany, N.Y. and its riverfront highway Interstate 787, for which NYSDOT has already committed to a $5 million feasibility removal study

- Baltimore, home to the infamous "highway to nowhere" US 40, which received a $2 million Reconnecting Communities grant to study removing, retrofitting or modifying the road

- Milwaukee, where advocates are building support for the removal of Interstate 794 following the successful removal of the Park East highway in the Wisconsin community

- State Highway 55 in Minneapolis, a surface "stroad" and frequent site of roadway crashes which advocates are fighting to reconstruct at human scale.

- Oakland, Calif., which recently won a Reconnecting Communities grant to study the possibility of removing I-980, among other alternatives, and which Streetsblog SF has written about in depth

- Seattle, which is also considering removal among the possible futures for urban highway with the aid of a Reconnecting Communities grant for State Route 99

- Tulsa, Okla., where transportation officials demolished the "Black Wall Street" neighborhood to make way for I-244; the Reconnecting Communities program is supporting a feasibility study for removing it.