One-tenth of American motorists, we’ve just learned, consume more than a third of U.S. gasoline.

This lead-footed cohort, dubbed “superusers” in a recent analysis, burn almost as much fuel — and, thus, spew nearly as much carbon dioxide — as all auto drivers in China. Or, reformulated, the most motor-dependent one-tenth of U.S. drivers burn the same amount of gasoline and thus generate the same carbon emissions as all motorists in the European Union and Brazil combined.

REPORT: We Should Stop Subsidizing EVs For All and Focus on ‘Super-Drivers’

The analysis, by Seattle-based Coltura, casts a hard light on America’s transportation culture. Unfortunately the firm’s policy prescription — new subsidies to entice superusers into buying climate-friendlier electric vehicles — is a mere Band Aid, and an ineffectual one to boot.

What Coltura’s Analysis Shows

The most startling revelation from the Coltura analysis is the rank inefficiency of the superusers’ rides. You would think that anyone driving 110 miles a day — the purported average for the 21 million superusers identified in the report — would rush to the nearest used-car lot and drive off in a high-mileage vehicle. But you would be wrong. Coltura’s traveling tenth eke out a measly 19.5 miles a gallon, on average. That’s a whopping 18 percent worse than ordinary drivers’ average.

The toll on superusers’ household budgets is immense: an average $530 monthly tab at the pump, according to Coltura. Upping their mpg to merely the same 24 mph average as other motorists would save them $97 a month. Those savings would hit $175 if the superusers clambered further up the mpg ladder and outdid the norm by the same percentage (18 percent) they now lag it. Annualized, that’s a cool two thou per vehicle.

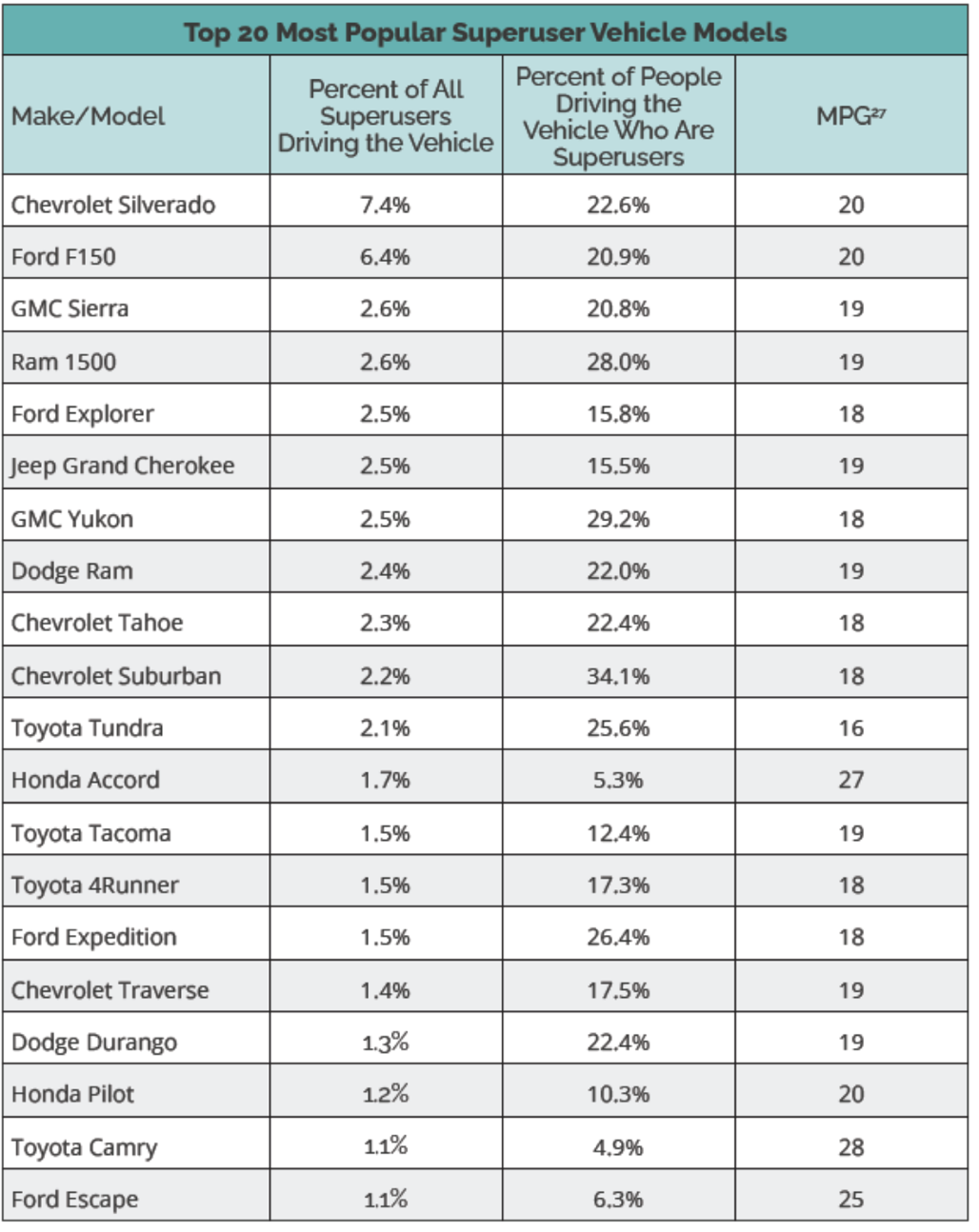

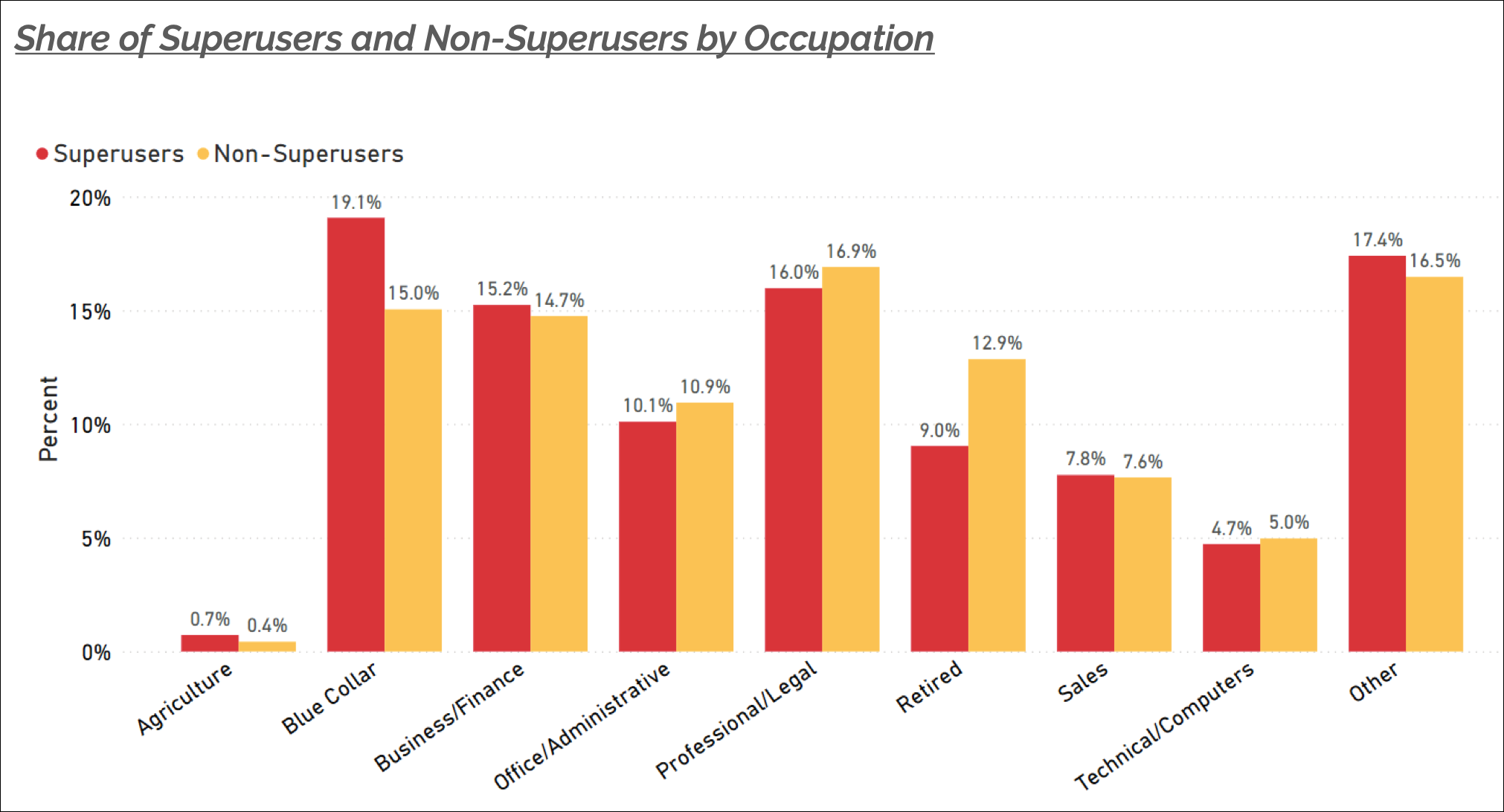

What’s that, you say, superusers are lugging drywall and cement mix and portable generators all over the county and can’t do with a more modest ride? Nonsense. According to Coltura, only 19.1 percent of superusers are blue-collar workers. Throw in another 0.7 percent who work in agriculture, and at most 20 percent routinely haul mountains of stuff requiring a pickup or SUV. The rest are professional/legal (16 percent), business/finance (15 percent), office/administration (10 percent) and other non-physical workers. Even if we prorate the 17 percent of superusers classified as “others,” at most 24 percent of Coltura’s traveling tenth qualify as Grainger’s “the ones who get it done” who might need a kick-ass vehicle with which to do it.

If you really want your head to explode, check out Coltura’s list of superusers’ 20 most popular vehicles. The Chevy Silverado is the choice of 7.4 percent of superusers, followed closely by Ford’s F-150 (6.4 percent). You have to drop down to #12 on the list to find the first vehicle that’s not an SUV or pickup. All told, no more than a handful of the top 20 are sedans.

Their Solution … And Mine

What to do? Ordinarily, one wouldn’t need to care that close to 20 million Americans are too Foxed-up or broke to dump their vampiric, oversized vehicles or off-ramp their road-warrior routines. After all, superusers have chosen to bust their budgets and warp their daily lives, right? Except, duh, the climate we all inhabit is breaking under their emissions — not to mention the myriad other damages from driving 110 miles a day: crashes, traffic, “local” air pollution. As I said up front, society has an interest in enticing them, somehow, into less-inefficient vehicles.

Coltura’s solution is to tie electric-vehicle incentives, messaging and perhaps even provision of charging infrastructure, to drivers’ current gasoline consumption. Validated superusers, based on sworn statements of odometer readings and vehicle make and model (hence, mpg) would qualify for extra rebates, financing and other inducements beyond those offered in the Biden Inflation Reduction Act. These would weaken the glue — economic, ideological or otherwise — that binds superusers to their gas-guzzlers even though it’s worth asking: Why do we need to subsidize someone into buying an EV when switching to a battery-powered car or truck would at once zero out the $6,000 that the average superuser shells out annually on gasoline?

At first blush, Coltura’s approach has a ring of reasonableness. But vagueness suffuses it, not just in the Coltura report, but in its lead authors’ 2022 podcast interview with climate-energy pundit David Roberts. In fact, on closer examination the whole idea comes off as a pig in a poke, with its administrative apparatus, the gaming, the appeals, the interminable wrangling to fashion the “right” incentives and eligibility. Not to mention the inevitable special pleading of “disadvantaged” motorists who almost qualify as superusers but not quite. And the jockeying in states or Congress to pay for the incentives and the bureaucracy.

What makes this prospect especially dispiriting is the existence of an alternative policy instrument that, compared to Coltura’s “targeted” but cumbersome intervention, could do far more to cut gasoline consumption — not just by superusers but by all U.S. motorists: concerted increases in U.S. motor fuel taxes.

Gasoline taxes can be raised in two ways: by boosting the U.S. excise tax, which has been stuck at 18.4 cents a gallon since Oct. 1, 1993 (losing half its heft to inflation since then); or by instituting a carbon tax, which would raise the prices of all fossil fuels including petroleum products.

The impact on usage would be small in the short run, but it would rise over time, as households switched to higher-mpg vehicles, cities and suburbs up-zoned, and cultural norms adapted to costlier driving. EV’s would be elevated, of course, but vehicle electrification would be only one of many means of getting off gasoline.

My regression analyses of U.S. gasoline demand — a subject I’ve studied for decades — suggest that a $1 increase in the price at the pump would trigger only a 3- to 4-percent drop in usage overnight, but triple that impact within a decade — roughly the same decrease as eliminating one-third of U.S. superusers’ consumption. But that’s just a start. My 1960-2015 data don’t reflect changing societal currents, nor do they capture digital tech’s potential to match people with nearby jobs or connect parallel travelers to enable work and play with fewer miles driven.

“Making other arrangements” in the face of climate chaos is how the social critic James Howard Kunstler once referred to this social reconfiguration. Sadly, as the caterwauling against New York’s congestion pricing program by entrenched interests from New Jersey politicians to teachers’ union bosses attests, the American ethos today would rather cling to dysfunction than attempt change.

This isn’t to make light of either the jarring changes that superuser motorists will face from robust fuel taxes, or the political difficulty of enacting them. (The website of my Carbon Tax Center is replete with potential antidotes to both, even as it acknowledges the difficulties.)

Nevertheless, these hurdles shouldn’t deter livable streets advocates from advocating much higher fuel taxation. Piling subsidies on subsidies, even if well-meaning, only makes our system more complex and opaque. If we don’t advocate for full-cost pricing that tells the truth about motorization, who will?