Piloting safe streets projects before rolling them out at full scale can help cities overcome public opposition to new ideas — or quash those projects before they start, a new study finds. And with millions in dollars of demonstration grants poised to come down from Washington, there's no more important time for practitioners to sweat the details when they do a trial run.

In a recent study published in the Journal of the American Planning Association, a team of researchers surveyed participants in Eugene, Oregon's first-ever shared scooter pilot, as an object lesson in how to shape public opinion through pilots more broadly.

That analysis could prove particularly timely in light of the final round of Safe Streets and Roads for All program, which is poised to give more than $400 million to planning and demonstration grants across the country. And considering that hundreds of communities have already won money from the "planning" half of that program, a lot of demos are likely on the horizon.

That's welcome news to planners like Kelcie Ralph, who co-led the study, and who has suffered through her share of traditional community engagement sessions that don't let the public witness the power of safe streets projects first-hand. And when neighbors are essentially invited to yell at public officials about abstract powerpoint presentations and 2D renderings that don't fully capture the importance of a new street safety concept, things can quickly get ugly.

"[This study] came from, frankly, a disillusionment with the public participation process," Ralph said. "It's hard to get stuff done that we think would make cities a better place, and I've always been really interested in the power of pilots to help with that."

Scooters, Ralph added, offer a particularly interesting case for the power of pilots to change hearts and minds — and that's precisely because they can be so polarizing.

"People have really strong opinions about scooters," Ralph said. "Even in a liberal place like Eugene, there are plenty of scooter-haters in the mix. ... And in a way, that's who you're most interested in; we're not super stoked to see what happened to the people who loved scooters from the start, because most of them will end up continuing to love scooters. What we really wanted was the people who anticipated profound harms and no benefits, and then to find out: did they change their tune when scooters hit the streets?"

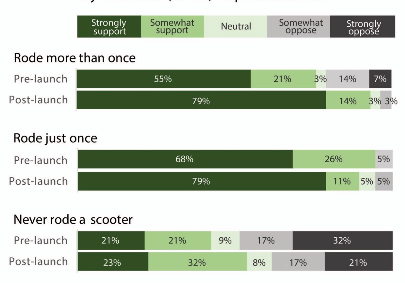

Turns out, Eugene's scooter pilot did increase support for a permanent scooter program — but not across the board.

About one-third of all respondents became more supportive of scooters by the end of the trial run, but 52 percent didn't change their minds. Meanwhile, another 15 percent actually soured on the mode — and interestingly, the bulk of the new naysayers had initially rated themselves as "strongly supportive" of the idea of adding new two-wheeled devices to their city streets.

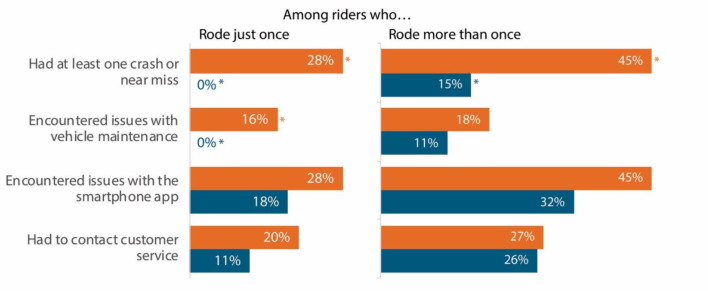

Ralph hypothesizes that's because the scooter provider hadn't ironed out all the kinks before the pilot launched.

"[Some of these participants] showed up, they rode a single time, and they had a bad experience of some sort," she added. "They almost got in a crash; they had problems with the app; there was an equipment malfunction with the scooter. For some reason, something about their ride went wrong. And that's a squandered opportunity; these are a cohort of people from whom the direct experience of the program actually ruined the program for them. ... It's a really useful reminder for practitioners that a pilot is not a panacea."

Ralph recommends that practitioners treat pilots less as a way to put the final tweaks on an imperfect product — or, as she puts it, "an opportunity to show a lot of people why this sucks" — and more as a "sales pitch" for a product or project they've already made pretty great, in response to the more traditional community engagement efforts that preceded them. (Eugene, for instance, conducted a series of pre-pilot listening sessions to build trust with residents and stakeholders, which resulted in the scooter company building parking corrals before a single vehicle even hit the streets.)

And once the pilot kicks off, Ralph says it's critical that cities keep the conversation going — especially in the form of frequent, systematic surveys, which capture public sentiment better than open-ended calls for feedback.

"If you just say 'our phone lines are open,' you're going to get a lot of complaints," she added. "The people who are delighted, and the people who are just fine — they're not writing in to say, 'This was great,' or 'This is wasn't as bad as I was expecting.' But your complaint box will be full, and it can mask lots and lots of support, or at least tacit approval."

Eugene also was careful to correct misconceptions they received throughout the pilot process, rather than simply letting residents go on believing that, for instance, their tax dollars were funding scooters at the expense of other city needs, or that parking infractions were rampant — neither of which was true. And they also turned to local leaders to help them dispel those ideas, regularly providing updates on how they were addressing problems so they could pass those messages along to their constituents.

But Ralph cautions against cities using pilots only as a way to show the public what they've got wrong about a new project — because they can and should listen to their constituents during the trial period, too.

"Some of the reviewers who read the paper initially said, 'Oh, you don't, you don't want any public participation; are you saying that planners should do their thing, outreach be damned?'" she added. "But that's also not what we want; we've been there in urban planning. That was not a good time either ... [It's not that] the things that we like should face less deliberation; they should just have an injection of experience. Because we can debate these things forever; they're new, they're scary, and until they're on the ground, it's really difficult to make a reasoned decision about them."

Ralph acknowledges that many bad roadway projects are barely subjected to any debate at all, including highway widenings that are can't be piloted because they're not easily reversible. Still, she says that even as we work to make autocentric infrastructure harder to build, the power of pilots can help us build sustainable projects faster and with more genuine public support — and that includes a lot more than just scooters.

"It works well with things like the outdoor seating projects or open streets events or bike lanes — and it works very well with bike lanes," she added. "It's great for anything [for which we can say], 'Let's get this on the ground see what happens to traffic, rather than engage in analysis paralysis and talk ourselves to death.'"