America should ditch its “one-size-fits-all” approach to encouraging EV adoption and focus on getting the highest-mileage drivers to go electric, while focusing on mode shift strategies for the rest of us, a new report suggests.

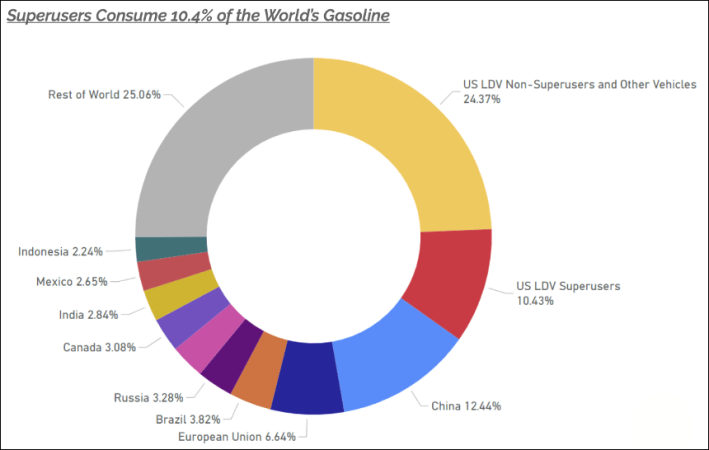

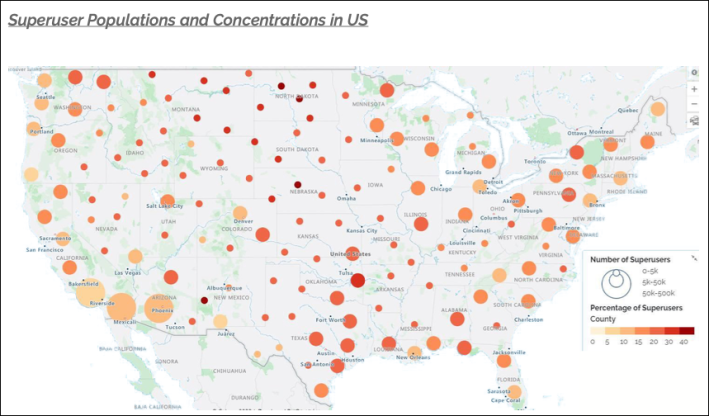

According to a sprawling new analysis conducted by the pro-EV nonprofit Coltura, roughly 10 percent of U.S. motorists — or 21 million people — are driving an average of 110 miles every day. And because those same motorists are more likely to drive fuel-inefficient vehicles like SUVs and pick-ups, they collectively account for 35 percent of the nation’s total annual gasoline use — only slightly less than the fuel consumption of the entire population of China, and nearly 60 percent more than the entire European Union.

Most existing electric vehicle incentives, though, don’t successfully target those fossil fuel “super-drivers,” as a buzzy New York Times article recently dubbed them. Instead, subsidies tend to opt for a wide-reaching strategy that seeks to put every American in an e-car regardless of how much they drive. In practice, since tax credits are non-refundable and historically have only applied to new cars, that means that pretty much only the wealthiest Americans take advantage, whether they consume a lot of gasoline or not.

OPINION: Instead of subsidizing ‘super-drivers,’ we should soak them

And in the process, the conversation about how to get non-super-drivers onto other modes gets buried, the report suggests.

“If [governments are] spending taxpayer money, they really have a responsibility to get the best bang for the buck,” said Janelle London, co-author of the report. “There’s no reason to have EVs in the world other than to displace gasoline; that’s the beneficial reason to have EVs.”

London says the reasons why super-drivers are spending their lives behind the wheel vary widely. Many, though, are tied to long-standing structural problems (aka American exceptionalism) that can’t be solved fast enough to beat the worst of climate change — unlike the barriers to walking, biking and transit that non-super-drivers face, which are often solvable with basic policy changes like infrastructure investment in urban centers.

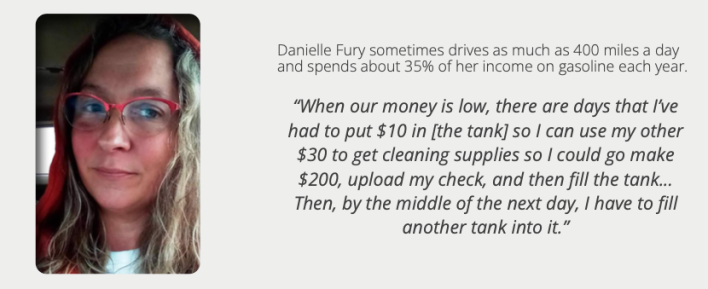

For instance, most (57.7 percent) of the mega-motorists live in rural areas to which it would take decades to bring the kind of jobs and services necessary to cut down their driving. And many people live on the fringes because they can’t afford to live closer to work — 42.9 percent have household incomes under the national median.

And while some of those problems could be solved by building denser housing in urban cores, that won’t solve the immediate problem of a quickly-burning planet.

“I envision a world in the future where no one has to be in a car,” London added. “When you think about European walkable cities and how wonderful that is, I dream of that. But I also know that we read reports from scientists every day that [make it clear] … we have to solve the problem of using fossil fuels. That just has to be a top priority. Otherwise, it won’t matter how great our transit is in cities, because our cities will be underwater. … I see it as near term [versus] longer term [solutions.]”

A better EV strategy, the Coltura authors argue, would aim subsidies not just at ultra-high mileage drivers who truly can’t switch from driving to other modes, but specifically “gasoline-burdened super-users” who spend a high percentage of their income on gasoline. That could mean focusing subsidies on Black drivers, who drop 12.4 percent of their paycheck at the pump — the average super-driver spends 10.2, roughly triple the amount of normal drivers — or focusing charging investments on routes frequented by the handful of super-drivers who don’t live in single-family homes that make it easy to charge a car overnight.

Both London and her co-writer Matthew Metz acknowledge that getting super-drivers to decarbonize their transportation may not be as simple as showing them the math on going electric — or promoting sustainable modes. In many parts of America, EVs — like transit, biking, and walking — have all fallen victim to the culture wars, which variously claim that battery-powered cars are “emasculating” and buses are hotbeds of crime; in others, all those modes are simply so rare that residents need education on their benefits before they even consider exploring another way of getting around.

But we can’t just throw up our hands.

“Money for climate mitigation work is extremely limited relative to the need,” said Metz, who co-authored the report with London. “If we [spend those resources] buying cars for people like my 92-year-old mom who drives a 100 miles a month — that’s got to be at the bottom of the list. We have to get extremely strategic … for the people that live in the hinterlands or whose lives require that they drive a lot, getting them in an EV should be a top priority. But an urban dweller that doesn’t drive very much? Maybe that EV subsidy should go to other purposes.”