During the COVID-19 stay-at-home advisories of 2020, the world quieted. As a community noise researcher, I felt the changes acutely: the busy road and subway line just outside my apartment window in Brookline, MA, emptied, and the car horns, vehicle engines, and train stop announcements that once served as my trusty backup morning alarm were replaced with the wind rustling through the trees, bird songs, and buzzing bees. The streets were so desolate that I was able to safely bike down the middle of the road and hear the beating of my own heart. That was something I hadn’t experienced since my childhood in rural Mississippi.

When COVID-19 shut down cities around the world, the unprecedented quiet allowed us to reflect on how loud our cities had become. For many, it was the impetus for a radical reimagination of how we plan our cities and a glimpse into how much quieter our world could be. I’ve attended countless community meetings calling for sound mitigation in communities near a crazy maze of interstates, next to an open-air baseball stadium that had been repurposed into a live concert venue, or under a flight path, and at each, it seemed like nothing could be done about our insanely loud cities. But with quiet streets, many of us began to imagine a world of car-free, pedestrian-friendly, walkable and bikeable streets. I envisioned a more relaxing world, one where we could enjoy the sound of chirping birds instead of the backup beeps of a construction truck. We could have and hold conversations with our neighbors without having to speak louder to compensate for the incessant horns from frustrated drivers. We could sit quietly in our living rooms, reading a book with the windows open, taking in the sound of a quieter din. And finally, we could sleep peacefully without waking up to a random car alarm.

I am an academic researcher trying to understand various aspects of community noise in urban environments: its sources, its distribution, and its acute and chronic health impacts in communities across the United States, especially vulnerable communities that are often the most susceptible to unhealthy community soundscapes. Noise, defined as unwanted sound, can be dangerous. Over 40 years ago, The Office of Noise Abatement and Control, a now-defunct office within the Environmental Protection Agency, estimated that one-half of our nation’s population was exposed to sound levels that were deemed harmful to human health, using a benchmark of 55 dB (about the sound of a moderately busy corporate office). In urban environments, in particular, the constant and seemingly inescapable soundtrack of planes, trains, automobiles, motorcycles, idling heavy trucks, sirens, and horns clock in much louder than 55 dB. Personally and anecdotally, in communities that are near major roads and interstates, for example, levels can consistently be at 70-80 dB or more, even at night. Decibels are on a logarithmic scale, and that 15-20 dB increase above “what should be” is quite noticeable – a 10 dB change roughly doubles perceived loudness.

The health impacts associated with higher noise levels are brutal. They can limit the quantity and quality of our restorative sleep and disrupt our mood so profoundly that our body activates a flight-or-fight response. In other words, each and every fiber of your being is coordinating to keep you alive during a situation it believes can potentially kill you. Your heart rate and blood pressure increase, you start to sweat, you become tense, and you may start trembling. Over time, this consistent stimulation in response to noise can lead to the manifestation of serious health outcomes ranging from hypertension to cardiovascular-related mortality.

Black and Brown communities, in particular, face huge aural burdens. A very quick scan of our nation’s urban planning policies and practices will clearly show you that we as a country have a refined knack for dumping acoustical trash – like highways, airports, and truck depots – into the laps of those with very little power to fight back. Most often, these have been predominantly Black communities like Rondo in Minneapolis, Sugar Hill in south Los Angeles, and North Nashville in Tennessee. Black and Brown lives have consistently been made to sacrifice acoustical environmental justice for the sake of everyone else’s convenience, oftentimes at the expense of their health and well-being. I know because I have lived that life.

So when cities grew quiet as everyone hunkered down indoors to stave off a global pandemic, I was happy to think that, at last, we were all afforded the opportunity to enjoy the peace and quiet that resulted from vehicles, trains, and aircraft activity grinding to a halt. That was until I received a message from a former student from the first phase of my life as a high school mathematics teacher in the Boston Public School system, wanting to know what she could do about the incessant firework activity in her largely Black and Brown community in Dorchester, MA.

The evening I received my former student’s email, I decided to bike down those wonderfully desolate streets to see for myself what was going on. As I entered Dorchester, I was immediately hit with an aural assault. Dorchester Avenue, whose incessant vehicular and bus traffic and the roaring of nearby Interstate 93 were usually among the biggest pre-pandemic sources of community noise, was practically empty, but the surrounding neighborhood was rife with firework activity that eerily sounded like gunshots, bombs, and heavy artillery. In other words, it sounded like a war zone.

As the founder of Community Noise Lab, I immediately got to work to document this noise and its impact on the health and well-being of Dorchester residents. We gathered noise complaint data from the city, set out sensors and recorders to collect decibel levels and audio, crunched data, and reached out to the City Council with our findings, which then prompted the creation of the first fireworks task force in the nation.

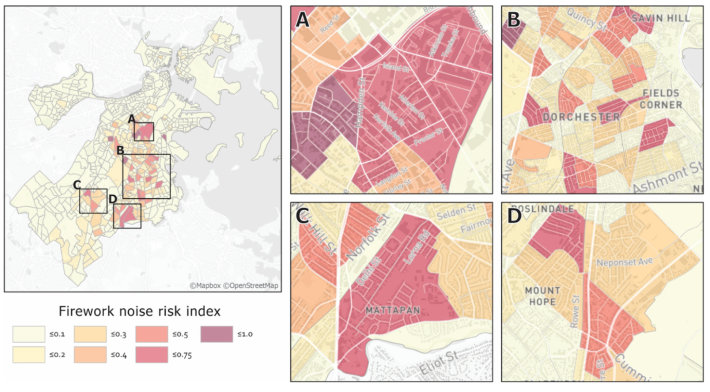

We found that during a time when the majority of our nation grew quiet, Black and Brown communities in Boston were continuing to suffer acoustically. While among some of the loudest areas in the city, pre-pandemic, Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan, for example, were logging thousands of complaints weekly through Boston’s 311 hotline and 911 due to the fireworks during the height of the stay-at-home advisories. From our sensor network, we found that during The Great Quiet, at night in these communities, 40 minutes of each hour had sound levels that were in excess of Boston’s noise ordinances. In other words, eight hours of peaceful sleep were whittled down to about three. We calculated a fireworks risk score as a function of firework vulnerability – looking at percentages of residents living in poverty, race, age (young and old), disability status, social isolation, and prevalence of shooting activity – and the number of firework-related calls for the entire city of Boston, down to the street. Unsurprisingly, the heaviest-hit areas were predominantly Black and Brown communities.

Unfortunately, this didn’t just happen in Boston; it happened across the United States. Black and Brown communities should have also benefited from the drastic reduction of transportation activities during our national lockdown. Instead, they became louder than ever.

It was and still is very unnerving to me that even during such an unprecedented event as The Great Quiet, a quieter and more peaceful community soundscape wasn’t afforded to all. Environmental injustices never took a break. History gives me the confidence to say that this was neither random nor unintentional. Unless something is done to mitigate our inequitable community soundscapes and snuff out the root causes – poor and apathetic urban and transportation planning and an over-reliance on superficial metrics that ignore or literally subtract out important factors such as individual and community perception towards sound as well as a sound’s character – the injustices will only continue to grow. Now that activities have mostly returned to pre-pandemic conditions, these acoustical injustices, especially transportation-related, seem to be accelerating and threatening the health and well-being of the Black and Brown people who are most exposed.