If you buy them an e-bike, they will come?

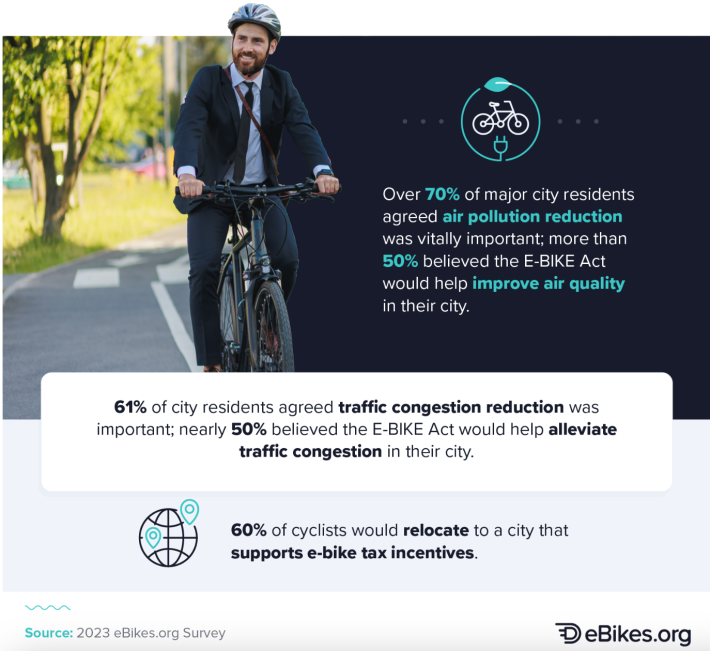

A whopping six in 10 cyclists would relocate to a city that offered them an incentive to buy an electric bicycle, according to a new e-bike industry survey — and the study authors say policymakers would be wise to start thinking of taxpayer-supported rebates as a potential economic development tool, as well as a strategy to cut emissions, congestion, traffic violence, and more.

"These incentives can make the environment, the human body, and the wallet just a little more optimized," said data journalist James Campigotto, who worked on the report.

"[Americans want] cost-effective commuting options and an improved quality of life, [which they can get from] just being outside in the sunlight and the breeze on a bike."

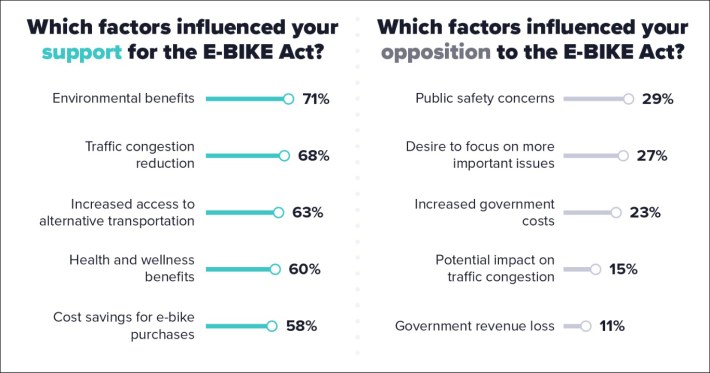

Even more respondents were fans of a federal credit that would help them purchase an e-bike anywhere they chose to live, with 70 percent supporting the recently-reintroduced EBIKE Act. Only a small handful (20 percent) of respondents, though, were aware of the details outlined in the newest version of the legislation, which would provide refundable tax credits up to 30 percent of the purchase price of a new pedal-assist bicycles priced under $8,000, with a maximum credit of $1,500.

The specific reasons why so many cyclists want e-bike rebates may be instructive for policymakers at all levels of government who struggle to see why it's worth investing in getting Americans on pedal-assist — particularly for those who are already riding without it.

About half respondents expressed optimism for both the environmental and congestion-cutting potential of the mode, which research shows often replaces more car trips than do traditional bikes. Some 63 percent, meanwhile, were encouraged simply by e-bikes potential to provide residents with a mobility alternative, suggesting that terms like "car dependency" and discussions of automobile dominance aren't just for policy wonks.

The 30 percent of riders who didn't support the EBIKE Act, meanwhile, cited "public safety concerns" as their major motivator — though it wasn't clear what kind of safety, exactly, they meant.

As a recent pair of victim-blaming New York Times articles made all too clear, even smart people like Pulitzer-prize winning journalists still conflate the dangers that drivers pose to e-bike riders with the supposed hazards of the mode itself — blaming even the most careful cyclists for their own deaths and ignoring the role that protected infrastructure, safer motorists, and better vehicle design can play in preventing crashes. Meanwhile, more legitimate concerns about e-bikes, like unregulated batteries that cause building fires and faulty break components found in cheaper cycles, can and have been at least partly addressed by incentive programs that require participants to buy from companies with strong safety requirements, and giving them the money they need to offset those higher-quality bikes' often significantly higher price tags.

"I’m sure not many people have a few grand to throw towards a bike," added Campigotto. "An incentive could help more people go for something less disposable."

Campigotto acknowledged that without safe places for people to ride, e-bike incentives are unlikely to get many non-cyclists to use the mode on a regular basis, and that the survey results are likely not representative of the public at large. If bike incentives can increase ridership numbers, though, — and perhaps even population numbers in cities that successfully lure new residents with great e-bike incentives— it could help create an army of advocates for protected roadway infrastructure that separates riders from drivers and pedestrians alike.

If you're looking for relocate to a community that already supports e-bike adoption, check out Portland State University's tracker of North American incentive programs here. For more resources on advocating for e-bike incentives in the city or state where you already live, check out PeopleForBike's toolkit.