It may be impossible for U.S. transit agencies to end the operator shortages and service disruptions that are leaving Americans stranded until they address a raft of human resources challenges happening behind the scenes, according to a new report that argues it's time for advocates to get involved.

In a follow up to their much-discussed report on the national bus and train operator shortage, researchers at Transit Center dug into the structural factors behind the troubling "lack of people power" happening at virtually every level of agency operations.

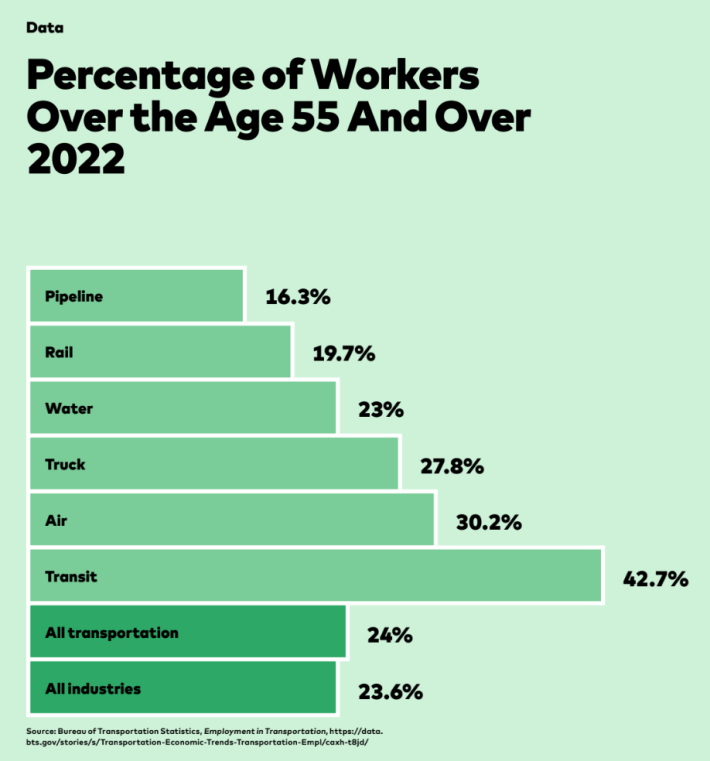

That includes not just bus drivers, but also the administrators who hire them, the planners who plot their routes, the mechanics who keep buses running, and many more. With 42.7 percent of all transit workers over the age of 55 and rapidly approaching retirement, the problem is only poised to get worse.

"Transit agencies in the public sector, in general, haven't kept up with the changing labor market in this country," said Laurel Paget-Seekins, a Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority veteran and the primary author of the report. "Jobs that used to be competitive, good, well-paying jobs that people would stay in for an entire career just aren't that anymore."

Over the course of more than 20 interviews with current and former transit employees, Paget-Seekins heard countless stories of agencies operating at an unsustainable level of stress that's come to be accepted as an industry norm, even among white-collar employees who never do the most obviously challenging front-line work, like driving a bus or cleaning a station.

In addition to the grueling, 24/7 labor required simply to keep the trains running — a particularly daunting task when money for basic maintenance has been slashed — transit employees are often forced to absorb outrage at public meetings about "spillover effects from policy failures that are outside their control," like housing shortages and underfunded mental health services. And even as agencies step up to help struggling riders with nowhere else to go and fix broken systems they didn't create, they're not always given extra resources to do it; they just stretch their budgets, and themselves, thinner and thinner.

Unsurprisingly, "high stress and burnout" were cited as the leading causes of transit agency departures during Paget-Seekins' interviews.

"In operations, you always have to keep going," she wrote. "You can't ever take a mental health day as an entire transit agency. You have to get the service back on the street the next day, no matter what happened the day before. And that creates a climate in which it's just really hard to recover, and learn, and grow, and have that rest and relaxation time everyone needs."

But that cycle of exhaustion isn't inevitable, Paget-Seekins said — and that until it's solved, agencies will struggle to deliver the level of consistent, high-quality service that riders deserve.

First and foremost, agencies should give more funding and focus to their "Human Resources" departments — a field which is 73 percent women, and in which Black women, particular, are over-represented, Paget-Seekins said. That might involve reconceptualizing traditional HR as departments of "People and Culture," empowered to be proactive in helping the agency and its staff grow, thrive, and create "slack in the system" so new workplace challenges don't simply get dumped on existing employees.

That process might start with overhauling onerous staffing requirements like civil service exams, and rewriting "government-speak" job postings that fail to attract top talent. Keeping that talent, meanwhile, will require spending more on professional development, which Paget-Seekins said can often help far more than the individual employees selected for additional training.

"Giving people opportunities to get training not only likely increases their interest in staying, it also helps improve our cultural problems," she wrote. "If we can train people on how to be good managers and supervisors, that'll help address some of the stress and burnout."

The Transit Center report cautioned advocates that turning transit agencies into great workplaces may not result in more on-time buses on the streets and well-maintained trains on the rails — at least not immediately. It will, however, build a strong foundation without which the sustainable transportation ecosystem can't possibly be expected to thrive, and without which many agencies are struggling to simply survive.

"I think that the internal workings of all government agencies, and not just transit agencies, are a little opaque," added Paget-Seekins. "To advocates, it feels a little second-order; you just want good service, and this is a little upstream of that. On some level, it shouldn't be up to the public to have to solve these problems. But given where we are, I think that having advocates understand some of this is necessary; promoting these solutions can help."