A new program will help smaller communities start the process of redesigning highways and other transportation investments that tore apart their communities — and shine a light on why it’s so hard for them to do it without outside help.

With support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a coalition of sustainable transportation nonprofits led by Smart Growth America recently launched the new Community Connectors program, which will grant up to $130,000 and a package of training and support services to each of 15 small and mid-sized communities across the U.S. “to help advance locally driven projects that will reconnect communities separated or harmed by transportation infrastructure and tap available federal and state funds to support them.”

And those funds are bigger than ever, even as many smaller communities struggle to secure them. As part of the Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhood Access and Equity Grants programs, Congress has allocated roughly $4 billion across five years specifically to address the damage caused by government programs like the interstate highway system, many of which were deliberately built through low-income communities of color with little power to resist them — as they still are to this day.

Experts, though, say far more money is available for this critical work, if communities know how to get it.

“So many times when we try to do something new, we feel constrained to remain within the program that has our name on it,” said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America, which is collaborating on the initiative. “But the overall transportation program is something like $450 billion, and a lot of it can be used for [these types of projects]. What an incredible way it would be to guarantee practically no change, if everyone sticks to their itty-bitty, less-than-one percent of funding and ignores the rest of the pot.”

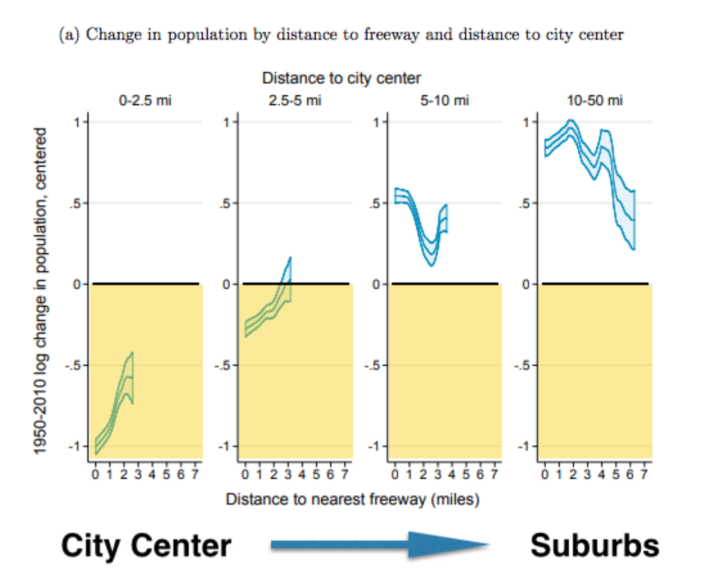

For cities between 50,000 and 500,000 residents, though, getting outside of the niche grant program box can be particularly challenging, not least because the transportation “investments” they were gifted by state and federal agencies diluted their local power. Studies have shown that each freeway built into a city center will result in an average 18 percent population loss —and all the accompanying lost tax revenue and political representation that comes with it —compared to the projected growth those places would have experienced had the freeway not been built.

“These roads gutted communities and chased people away, and now you’ve got cities with less money coming in because we supplanted their neighborhoods with highways,” Osborne adds. “When you dedicate so much of your downtown property to the movement of motor vehicles, you’re trading away the potential for a lot of economic development, and eventually, [it results] in a weaker government.”

And small communities with few resources, of course, aren’t particularly well-positioned to do difficult, path-breaking work — like turning freeways into boulevards.

“In transportation, the problem statement is usually the same: to provide more space for roads and cars; [Dismantling transportation barriers] requires communities to figure out another path, and to do it in their free time, without a lot of examples of how to do it,” Osborne said. “You have to have either a lot of capacity or a lot of funding to make that happen — and small government agencies are struggling just to keep up with what’s demanded of them.”

By increasing their capacity, Osborne is hoping the Community Connectors program will not just make disempowered cities more competitive for precious grant dollars, but better equipped to center the needs of their most disempowered residents in their eventual projects so they aren’t displaced. She suspects a lot of the money will be used to organize community participation efforts, in addition to things like staff salaries and data collection.

Even with all those important assets in hand, though, Osborne also suspects small communities will still face hurdles to remediating highway harms. That’s part of why all grant recipients will be required to attend an in-person gathering to learn from one another’s challenges — which will also give the grant administrators an opportunity to learn from them, and bring their message back to Congress.

“In the end, we really want to tell a story about these communities,” she adds. “A lot of people view [highway redesigns] as a money problem, but a lot of this is probably going to be a policy problem. Will whoever owns the infrastructure be willing to cooperate — or be required to cooperate? Will they stick to inaccurate traffic modeling, and will they be forced to stick to inaccurate modeling? Will the federal government really accept a new way of looking at things? One thing I expect is we’re going to discover is that we’ve put up a lot about the barriers to reversing this damage, and when Congress comes back to this process, they’ll need to do more than just throw money at the problem.”

The Community Connectors program is accepting applications until July 15, 2023.