The states with the highest rates of distracted driving per mile aren't always the states that report the most distraction-related crashes, or the ones with the most lax distraction laws, a new report finds — and it could be a sign that America needs a broader set of tools to fight the deadly epidemic.

For a new report from mobility data company Arity, researchers analyzed trillions of miles of anonymized data from mobile phones across four years to determine which U.S. drivers are most likely to check their cell per mile they spend behind the wheel.

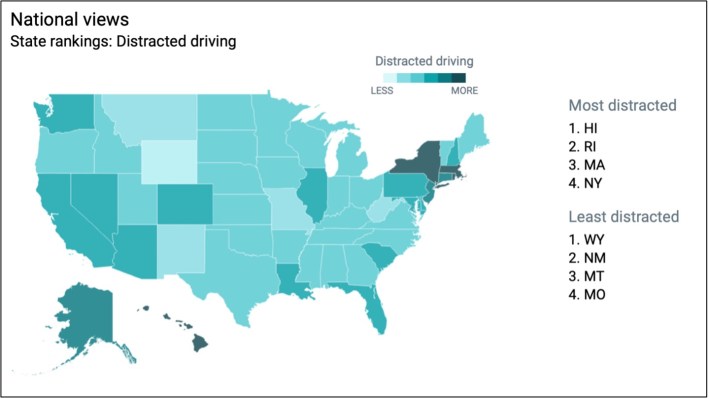

The results, at first, might seem pretty shocking. Among the least distracted drivers in the nation were Wyoming, which allows teenagers with graduated drivers licenses to use phones behind the wheel, and New Mexico, which has also ranked as the state with the highest number of reported distraction-related crashes for the last three years in a row. Those two states were followed by Montana and Missouri, despite being two of only three states in the nation not to make texting behind the wheel illegal. (The third is Nebraska.)

The most frequently distracted motorists, meanwhile, were found in Hawaii, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, all of which were commended for having "optimal" distracted driving laws by the Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety. New York, meanwhile, landed its number four spot on the list in large part thanks to New York City, which ranked as the most distracted metro in the entire country — despite also being probably the safest and most walkable metro, too.

Those eye-popping stats, of course, don't prove that distracted driving laws don't work, or that building complex, pedestrian-centered cities doesn't save lives.

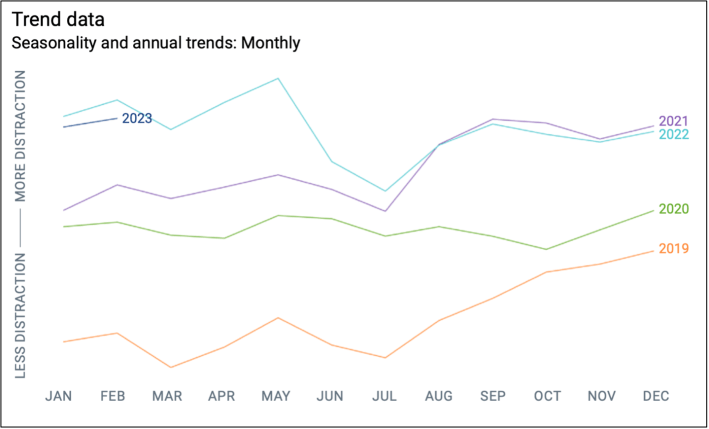

The researchers only looked at distraction events per mile driven rather than per capita or per licensed driver, which means motorists with lengthy highway commutes could potentially skew the data. The analysis also found that distraction went down on weekends nationwide, when roads tend to be less congested, as well as on summer days when motorists aren't running into as many weather-related slowdowns that might compel them to pay more attention — if only to keep themselves safe from a high-speed crash.

From that perspective, it makes perfect sense that that the long, open roads of the mountain west and Midwest might compel motorists to put their phones down — and why, when they do pick them up, they're more likely to be involved in fatal collisions at blistering speeds. Multiple studies have shown that simply designing roads for lower velocities slashes the severity of distraction-related crashes, even if they may also compel motorists to ogle their phones, or infotainment screens, or to let their mind wander from the road for any other reason.

Even when congestion and good road design manages to slow speeds somewhat, though, distracted driving can still be deadly — particularly for pedestrians and other vulnerable road users. And considering that Arity recorded a 30-percent increase in the average rate of phone-related distraction incidents per mile over the last four years, policymakers would be wise to attack the problem from many angles.

"I just think it’s addictive," said Megan Jones, analytics director for the company. "Mobile apps have an incentive to create engaging experiences that will draw you in and get you to come back and regularly interface with them ... Unfortunately, that happens when people are driving, too."

If they want to combat distracted driving — and far more importantly, the deadliest crashes it helps cause — Jones stresses that states don't only need to design safe roads and adopt strong prevention laws, but also associate those laws with strong fines, as well as strong marketing campaigns that make it widely known that anti-distraction policies exist and will actually be enforced. (We might also add that it's critical to close common loopholes that make distraction laws ineffective, like banning handheld cell phones but still allowing hands-free devices that can be nearly as distracting.) She also says that positive messaging can play a role, too.

"Instead of only focusing on disincentives and only on areas where drivers might happen to be caught, we believe we can also approach improving safety through a different path of providing coaching and incentives through insurance savings," she adds. "We’re able to see over time how people regularly drive, not just how people drive when they suspect a sheriff is around the corner. Which is not to say that distraction laws don’t work; it’s just that distraction laws aren’t everything."

Considering the well-documented challenges of enforcing traffic laws equitably, another strategy should probably be added to the list, even if it's politically unpopular: programming all distracting tech to simply stop working when a car is in motion, at the very least when the driver is alone in the vehicle.