When Waiting For the Bus In a Wheelchair Becomes an Act of Protest

12:01 AM EDT on April 10, 2023

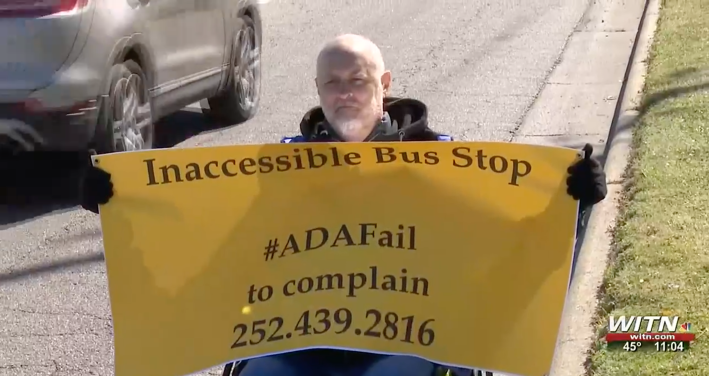

Photo: Steven Hardy-Braz.

When Steven Hardy-Braz arrived to be booked at the Pitt County jail on March 16, the sidewalk leading up to the door wasn't accessible to his wheelchair.

The irony was not lost on him. The 56-year-old Farmville, N.C. resident had just been arrested under allegations of "willfully impeding traffic" on another inaccessible road in nearby Greenville, where Hardy-Braz had no choice but to sit in a driving lane with a posted speed limit of 45 miles per hour as he waited for a bus ride to a medical appointment. Unlike the jail, though, there was no sidewalk at all next to that dangerous road, never mind a curb ramp, a shelter, or a bench. Like so many other bus stops in America, there was nothing but a sign on a pole in the grass.

"I was explaining to the officer, 'I'm just sitting here in my wheelchair next to this inaccessible bus stop,'" he said. "And I was arrested for such."

Hardy-Braz acknowledges, though, that he wasn't "just" waiting for the bus in a hazardous environment; he was also staging a protest. He'd taken to carrying around a bright yellow sign urging his neighbors to call the North Carolina Department of Transportation to report a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act at a stop along a road maintained by their agency.

And it wasn't his first encounter with police, either. In the 16 months since he was struck by a distracted driver while riding his bike and began relying on an assistive device for much of his daily mobility, many of his neighbors had called law enforcement on him, alarmed at the sight of a man wheeling through high-speed car traffic. Some bus drivers would lower their ramps for him at inaccessible stops, while others — including two, he says, who passed him by on the day of the arrest — would claim it wasn't safe to stop the bus just a few feet additional from the curb, leaving him stranded. (The transit agency did not return a request for comment). He even landed on the local news a few times.

"Some people would call the police, and the police would come out and threaten me," he said. "Other people were nicer; they'd offer a ride or something. I was like, 'Thanks, but will you offer to join me making sure that things are accessible instead?'"

Those police had mostly given Hardy-Braz warnings for his behavior; some even offered him rides, which he sometimes accepted. Eventually, they began issuing him tickets, including one he received just one day before his arrest — though by then, he says he wanted to be cited, because it might give him the opportunity to advocate for accessibility improvements in court. Despite months of advocacy and more than 20 written requests to NCDOT about inaccessible stops in nearby towns, he'd seen little change, and he was starting to suspect that his fight would be a long one.

"They've had 33 years to fix this in my town, and they haven't," he said, referring to the 1990 passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act

What he didn't expect was that he'd eventually be arrested — or what would happen when he arrived at the jail.

When asked by police officers if he experienced depression or thoughts of self harm, Hardy-Braz was honest about the mental health struggles he's dealt with since the crash that left him with diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety, along with near-constant physical pain from his injuries. He says he was placed on suicide watch, after which he was stripped of his wheelchair and all of his clothes, which were traded for an apron he couldn't use to harm himself. He says he was also stripped of the pain medication he's depended on since the crash, and he soon began experiencing painful symptoms of withdrawal. He suffered for what he estimates to be eight or nine hours before the judge finally granted him an $1,000 bond that allowed him to be released awaiting trial. (The Pitt County Sheriff's Office did not reply to a request for comment.)

While that traumatic experience has shaken him, he says his work is not done.

"I feel what I did was right, and they feel what I did was illegal," Hardy-Braz added. "I’m not sure what my future actions will be, but I know I will still be fighting these issues."

Hardy-Braz's fight for the civil rights of people with disabilities started long before his arrest — and long before he began using a wheelchair himself.

A school psychologist and ASL interpreter by training, he was one of the few hearing students to attend the internationally recognized Gallaudet University for the deaf and hard of hearing, where he witnessed firsthand just how different life could be for people with disabilities when every element of their immediate environment actively centered their needs. And he also learned that if he wanted to help create those environments, he needed to follow his classmates' lead.

"They challenged me — like, 'You know, if you're gonna come work with us, it can't be out of pity. It has to be kind of out of being an ally,'" he said. "And I learned that part of being an all with any group is realizing that you're not a member of the group. And if you have some kind of privilege, it's fine to use that privilege — but as soon as you can use that privilege to open the door, you have to step aside and get out of their way."

He later brought that insight into his work as a sustainable transportation advocate and passionate cyclist, serving as an interpreter at bike events across the country and a frequent organizer of local rallies and advocacy campaigns for safe and accessible streets. In July of 2021, in honor of the 31st anniversary of the Americans with Disability Act, he set out on a 10 mile bike ride to document at least 31 fixable ADA violations in his tiny hometown of Farmville, which is just 3.2 square miles; he found over 100.

Just four months later, a distracted motorist with no license, tags, or insurance struck Hardy-Braz from behind while he was pedaling home to that small town on a road with no bike lane. He flipped over her car, fracturing his spine and leaving him with partial paralysis and near-constant pain. He can sometimes manage a few steps on his own with a cane when his pain and his medications are well-managed, but he still struggles to walk, and his life is dominated by constant medical visits and looming bills. Most of all, though, he says the experience has reshaped the way he sees the world — and his own advocacy.

"I realized, 'Wow, I haven't really done enough as an advocate in my own town to make sure, sidewalks are accessible,'" he said. "But now that I have legal standing as a disabled person, I'm going to stop failing to do so."

Hardy-Braz's style of advocacy, though, hasn't always been welcomed by city officials.

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for Greenville police said that Hardy-Braz's arrest was a last resort following "numerous complaints over a span of days" about the "ongoing public safety issues created by his actions." The day of his arrest, they claim an officer "initially warned him (again) and asked him to move off the road so as not to impede traffic. Mr. Hardy-Braz [did so], but was observed going back to sit in the middle of the road less than three minutes later." (Hardy-Braz maintains that he remained as far to the rightmost edge of the roadway as he could, and that motorists had to move over "just a few feet" to accommodate him.)

In a separate statement to local media, a different city spokesperson chastised him for "advocat[ing] in a way that endangers himself and other motorists on busy city streets,” despite the fact that Hardy-Braz was not in a car at all at the time of the incident; they also said officers "observed that [Hardy-Braz] is not reliant on public transportation as he drives his own vehicle from his house in Farmville to Greenville," and emphasized that he could have taken an accessible on-demand transit option called the Pitt Area Transit Service instead.

But Hardy-Braz is often reliant on transit — even if he doesn't meet the police department's seemingly narrow definition of the term. He says that his injuries sometimes make driving itself painful for him, particularly for long trips, and that complementing short drives with public transportation has been important to him as his medical bills mount. PATS buses, though, cost $7.00 each way, compared to just $1 for fixed-route service and they require 24 hours notice to book; the one time he tried to use it, it arrived so late he had to reschedule his medical appointments twice, and when he stopped to pick up a second passenger, the driver "had to physically and painfully climb over my damaged body in order to switch the two wheelchair using passengers around, and still struggled to safely secure me in my wheelchair."

More to the point, though, Hardy-Braz says people with disabilities should be able to take any kind of transit they want, for any reason at all — and the only reason they can't is because the city has been slow to build them the basic infrastructure they need to do it safely. The ADA generally only requires municipalities to make streets and bus stops accessible when they're repaired or reconfigured, and even then, they often don't until they're sued, citing a lack of money, staff, or other competing priorities.

In a response to a written complaint he made prior to his arrest about Greenville's inaccessible bus stops, the NCDOT told him that the agency "is authorized to construct new sidewalks adjacent to State highway improvement projects at the request of the municipality provided the municipality agrees to reimburse the Department of Transportation for the actual construction cost of the sidewalks" — a response which sounds to Hardy Braz doesn't accept.

"I'm trying to tell people there's a bigger issue here about civil rights," he added. "For people crossing the road, [change] only seems to happen when enough people pay for it in blood. ... We built this environment, and often, people like me end up with disabilities because of our how we built this environment. But we have the power to change it."

Kea Wilson is editor of Streetsblog USA. She has more than a dozen years experience as a writer telling emotional, urgent and actionable stories that motivate average Americans to get involved in making their cities better places. She is also a novelist, cyclist, and affordable housing advocate. She previously worked at Strong Towns, and currently lives in St. Louis, MO. Kea can be reached at kea@streetsblog.org or on Twitter @streetsblogkea. Please reach out to her with tips and submissions.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog USA

Tuesday’s Headlines Fix It First

How voters incentivize politicians to ignore infrastructure upkeep. Plus, are hydrogen trains the future of rail or a shiny distraction?

Why We Can’t End Violence on Transit With More Police

Are more cops the answer to violence against transit workers, or is it only driving societal tensions that make attacks more frequent?

Justice Dept., Citing Streetsblog Reporting, Threatens to Sue NYPD Over Cops’ Sidewalk Parking

The city is now facing a major civil rights suit from the Biden Administration if it doesn't eliminate illegal parking by cops and other city workers.

Five Car Culture Euphemisms We Need To Stop Using

How does everyday language hide the real impact of building a world that functionally requires everyone to drive?