Last week, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration released what seems, at first, to be a shocking statistic: a sample of more than 7,000 road users who were killed or injured in car crashes across America, 56 percent of them tested positive for impairing substances when they arrived at the hospital.

That stat spawned countless horrified headlines and interviews with experts troubled by the news of a potential DUI epidemic, including research psychologist Amy Berning, who told CNN that the results sent a clear signal that "we need to ensure that we are continuing our efforts in prevention and various countermeasures to address impaired driving.” And NHTSA, for its part, answered that call promptly, with the announcement of a $13.2-million national media campaign warning motorists to "drive sober or get pulled over," and a holiday-season enforcement crackdown during the second half of December.

Buried deep in those articles, though, were a few critical nuances that complicate that narrative — and might make the agency's short-term focus on education and enforcement seem like a woefully inadequate response.

More Than Half of Serious Crashes Involve Drugs, NHTSA Study Suggests https://t.co/LrxrZosTUG

— Robert Farley (@drfarls) December 15, 2022

The first problem with the coverage was that the study didn't only include drunk and drugged drivers. It also included pedestrians and bicyclists — people who had made the responsible choice not to get behind the wheel, but were struck by a motorist nonetheless.

Moreover, those road users were also tested for a wide range of potentially impairing but totally legal substances, like anti-depressants and over-the-counter medicines, which NHTSA's educational campaign won't mention and its enforcement campaign can't touch. And the researchers were also careful to note that specific impairment effects of some of those substances, like cannabinoids and stimulants, can vary widely based on dosage, an individual's level of tolerance, and which other impairing substances they're combined with, particularly if that substance is alcohol, which tends to make every other drug more dangerous.

To complicate matters, a lot of those drugs show up on tox screens for multiple days after they're consumed — meaning that many of the drivers in the sample may have been completely sober by the time they got behind the wheel.

Unsurprisingly, the study's own researchers stressed that their results "should not be used to imply impairment or increased risk associated with drug presence."

Or, to put it more bluntly: a lot of U.S. road users do drink or take drugs before they're involved in a collision. But that doesn't necessarily mean that's why they crashed — or that the other systemic contributors to U.S. road deaths don't urgently need to be addressed.

To be abundantly clear: none of this is to say that impaired driving, and especially drunk driving, isn't extraordinarily dangerous. A motorist's odds of getting into a car crash double at a blood-alcohol concentration of 0.05, which is the legal limit only in Utah, and they roughly triple at 0.08, the limit in most other states. The universe of potential effects from the universe of impairing substances a U.S. driver might consume include decreased muscle coordination, distorted perceptions, increased risk taking, and so much more. The correct number of drinks, or pills, or other delivery mechanisms for impairing substances that a driver should take before she gets behind the wheel is always zero.

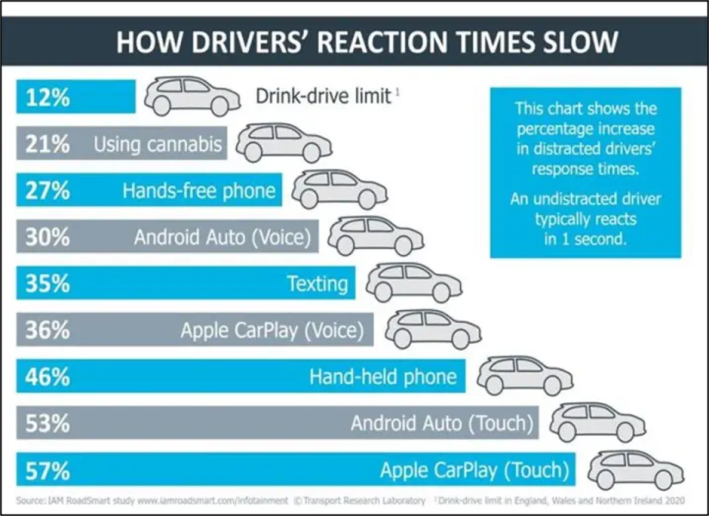

A lot of those deadly effects, though, are also present in people who are sleep-deprived, or stressed, or fiddling with a NHTSA-approved "infotainment" screen embedded in the dashboard of their car — and in some cases, those effects can be as bad or worse than knocking back a couple of beers. One UK study found that using Apple's CarPlay system slowed drivers' reaction times nearly five times as much as driving with a blood-alcohol level of 0.08 — but CarPlay is legal on U.S. vehicles, even as U.S. regulators spend millions on anti-distracted driving campaigns to politely request drivers not use it.

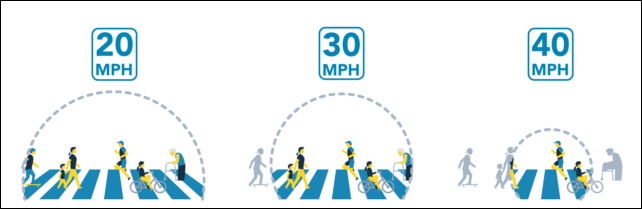

Even road design itself encourages sober motorists to do many of the dangerous things that drunk drivers do, like traveling at lethal but completely legal speeds — and U.S. DOT rubber-stamps many of the design guides that their counterparts at the state and local level look to as they make those deadly design choices. Even without beer goggles on, a motorist traveling 30 miles per hour has a measurably narrower field of vision than a motorist traveling 20 miles per hour — and yet speed limits of 35 miles or 45 per hour are common on U.S. arterials, many of which form the spine of the transit lines to which residents routinely walk.

The big takeaway from NHTSA's latest impaired driving study should not be that America is overrun by reckless criminal drug users who must be scolded and stigmatized into compliance. Nor should it be that, in the absence of comprehensive data about what, exactly, constitutes "impairment" in a country where new legal and illegal drugs are being invented constantly, we should err on the side of criminalizing anyone who gets drunk or high — regardless of whether they are a driver or a pedestrian, an chemically-dependent addict or a careless kid driving home from a kegger, one cocktail deep or 20.

The big takeaway should be that using impairing substances is incredibly normal, even if we wish it weren't — but with the right approach, that incredibly normal human behavior does not have to result in deaths on U.S. roads. We can design vehicles that are impossible to start when we have alcohol on our breath and build bus lines home from the bar; we can design narrow roads that make it physically challenging to speed whether we are impaired by benzos or a bad night's sleep; we can give people safe choices to move through the world no matter what they've consumed or why.

To do that, though, we must first reckon with the ways in which impaired driving policy in the U.S. is not designed primarily to make roads safer, but to shift the blame for roadway deaths back onto individuals rather than systems over which the powerful have control. And if the uncritical response to NHTSA's latest study is any indication, we are not ready for that conversation yet.