A new initiative aims to put thousands of purpose-built transportation bikes in the hands of people in underserved countries — and in the process, sparking a conversation about the role of bike design itself in making green mobility accessible.

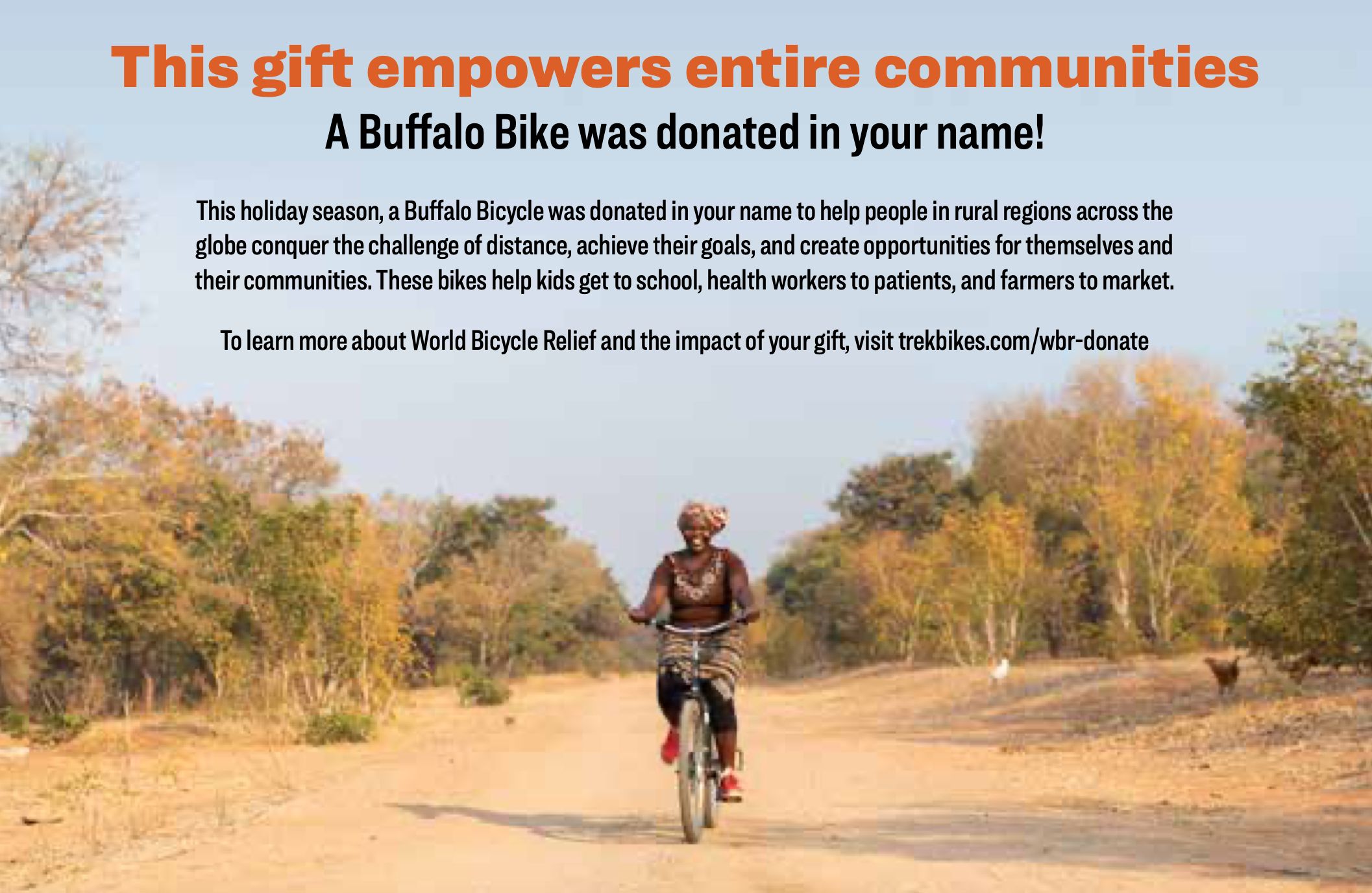

Throughout the month of December, U.S. bike manufacturer Trek has announced it's matching up to $500,000 in donations for World Bicycle Relief, an organization that provide residents of communities with minimal roadway and transit infrastructure with bikes specifically designed to meet their daily needs. Founded in 2005, the group has distributed more than 635,000 cycles to date in towns throughout Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, which their team estimates has enhanced the mobility of more than three million people, since the bikes are shared by a family of five people on average.

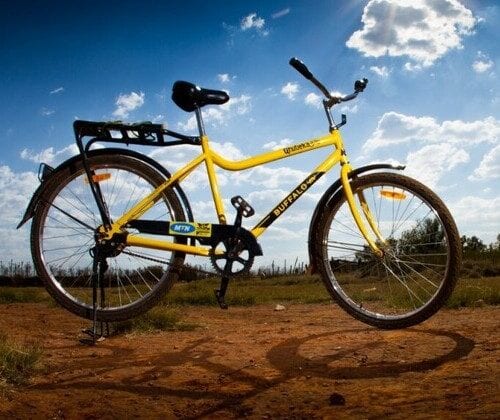

That success, though, might not be as profound without the right bike: namely, the Buffalo bicycle, which Trek helped the group to design. And while that super-sturdy vehicle was built specifically to handle dirt roads and heavy loads that residents of auto-centric countries would be more likely to transport by car, some of the group's supporters have wondered whether vehicles like it might have a place in U.S. communities, too — and how their absence affects Americans' likelihood to ride.

"People in the U.S. ask me all the time, 'Can I buy this bike?'" said Eric Bjorling, Trek's brand director.

Bikes like the Buffalo, though, are far from the norm in U.S. shops.

At a cost of just $165 to produce — about 40 percent of what it costs consumers to buy the cheapest adult bike on Trek's website — it's a minimalist ride designed for longevity above all else, with coaster brakes that don't require hard-to-find cables to fix and heavy-gauge spokes that are unlikely to snap during heavy use. "Accessories" (which are actually necessities for transportation cyclists) almost always cost extra in America, but things like storage racks and ergonomic seats come standard on the Buffalo; complex gearing and finicky disc brakes that require a professional mechanic to adjust, meanwhile, are nowhere to be found.

It's tempting to call it a workhorse, but it's more accurate to compare it to its namesake animal, which one of World Bicycle Relief's directors describes points out "has survived everything, despite a high number of predators."

Of course, bike design alone can't protect riders from every "predator," at least without safe road design to match. The countries in World Bicycle Relief's service area report some of the highest traffic fatality rates in the world despite having some of the lowest rates of vehicle ownership, with Malawi alone posting a staggering 31 deaths per 100,000 residents compared to the United States 12.4. (France, for comparison, posts 5, while Vision Zero leader Sweden reports just 2.2.)

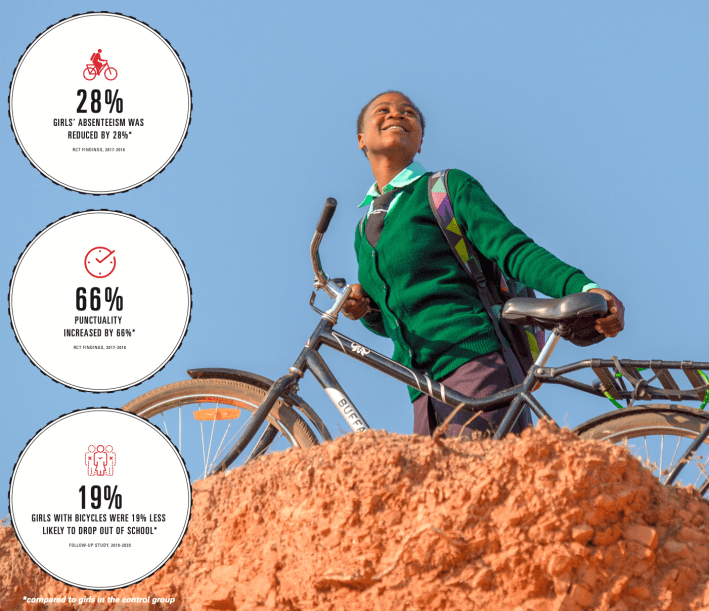

When it comes to helping riders overcome less-deadly challenges, though, Bjorling emphasizes that sturdy, Buffalo-style designs can be critical to keep people riding. And in countries like Malawi with little mobility infrastructure, that can mean the difference between accessing clean water or not, or girls going to school instead of staying home and missing their education completely.

In car-crazy America, meanwhile, purpose-built transportation bikes can have a meaningful impact too, if only by giving residents an alternative to a car commute they can't afford, or a multi-transfer bus ride that would take even an able-bodied person three times as long as riding a direct route on her own power. Studies have shown that many would-be cyclists are put off of riding because the bikes they can access most easily don't meet their needs, whether because those vehicles can't carry a day's groceries without the addition of a pricey rack or because riders don't have the time, skills, or desire to become a DIY mechanic when something breaks.

The trouble is, Bjorling says the U.S. bike industry isn't building many Buffalo-style bikes — and even when they are, studies show that many bike shops are too condescending, or even outright discriminatory, to make transportation-focused riders feel welcome.

"The cultural view of cycling in the US is primarily about recreation," he adds. "But a bike designed like a Buffalo bike still has significant value in the US; we have our own transportation deserts where people can’t access essential services."

Bjorling says that Buffalo-style bikes area gaining some ground on U.S. roads — in the form of bikeshare vehicles. To increase stateside ridership, though, maybe the retailers of private bikes should learn from World Bicycle Relief's example and bring more affordable, accessible, do-anything options to market, and focus more of their energies on selling to the people who need bikes the most. (And yes, they can still offer a universe of customizable components to veteran cyclists, too.)

"How did we get to this place where you walk into a bike shop and the bar to entry is so high?" Bjorling adds. "I think part of it has to do with the fact that cycling is an industry where people take things very personally, and it attracts people who have very unique ideas for [how their bikes should be ridden]. And I think that works to our detriment a little bit."