U.S. streets are transforming into testing grounds for automated vehicle technology — but both Congress and state governments are failing to protect road users who didn't sign up to be guinea pigs, a new report says.

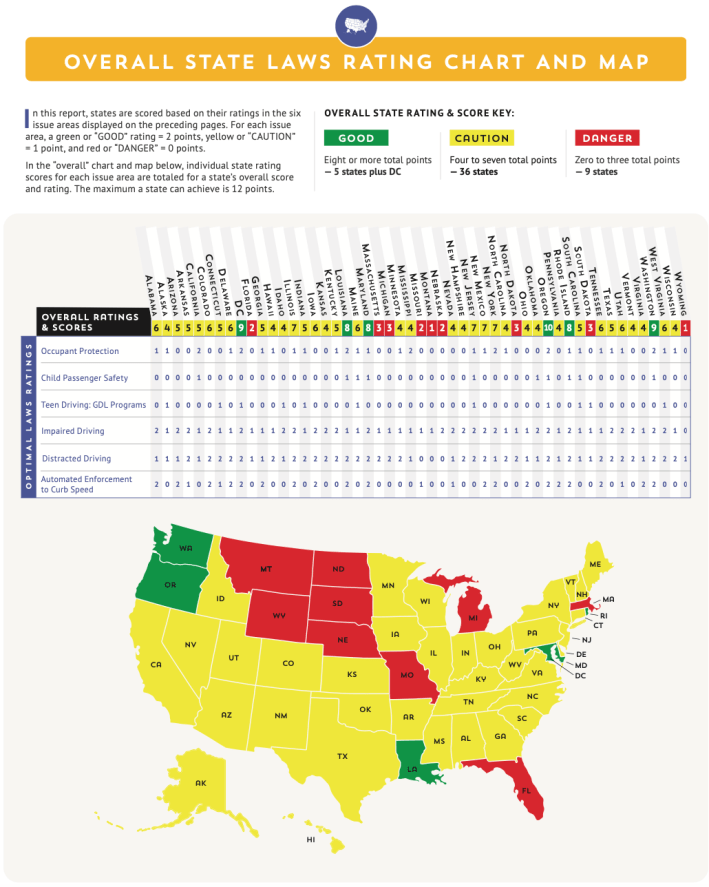

In its signature annual roadway safety scorecard, the nonprofit Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety graded all 50 states on the strength of their traffic laws — and for the first time, warned that no U.S. community has taken sufficiently aggressive action to manage the still-uncertain impacts of robocar technology. (An estimated 90 percent of new vehicles sold today come equipped with some form of advanced driver assistance system, like automatic emergency braking, lane-centering, or Tesla's erroneously named Full Self Driving.)

That failure begins with the federal government, which should theoretically be responsible for setting vehicle safety standards for advanced driver assistance systems that keeps faulty tech off U.S. roads — but has so far failed to set any standards at all, or even to provide consumers with basic information about which systems are most and least effective. The Advocates point out, though, that state governments control the laws that govern motorist behavior, and as the line between a car and its driver blurs, it's creating new opportunities for those governments to intervene.

The problem is, virtually no government is intervening — and people may be getting hurt as a result. The most recent data from the National Highway Traffic Administration found that advanced driver assistance systems (and its more-advanced cousin, "advanced driving systems") were involved in more than 800 crashes and 18 fatalities between July 2021 and October 2022, though the technology's role in those collisions is unclear, because critical data was redacted from the public.

"It is far too early to assess whether automated driving technology has the potential to reduce our nation's mounting roadway death and injury toll," the report authors wrote. "However, the lack of federal performance standards, strong government oversight, adequate consumer information, comprehensive data collection and effective industry accountability could very well sink this possibility."

Perhaps the simplest thing state governments can do to make roads safer from the unintended effects of robocars is to remember that they're still ultimately being operated by human drivers. Experts have long warned that the presence of an advanced driver assistance system can actually encourage motorists to check out behind the wheel, but the Advocates' report points out that a staggering 40 percent of U.S. states have failed to institute model distracted driving laws to hold them accountable when they do.

"We're not just concerned about traditional distracted driving, like texting; we’re also concerned about automation complacency," said Cathy Chase, president of the group. "Even if there are warnings in an owner’s manual, it’s human nature; if people think the system is taking care of common driving tasks for them, they’ll look for something else to do. They’ll say, 'of course I can send that quick text; of course I can watch this TikTok.'"

Even if a human driver is behaving perfectly, though, that doesn't mean her semi-autonomous car is — and that's the feds' fault. Chase points out states can't require AVs to pass a basic DMV "vision test" like flesh-and-blood motorists, nor can they require automakers to have procedures in place for when an ADS vehicle is involved in a crash, the way a human driver might learn in driver's ed.

Those are just two examples of the dozens of basic tenets that the Advocates hope NHTSA will adopt in any upcoming rule-making, which Congress is anticipated to ask the agency to do next year. Chase emphasizes, though, that regulators may need to expand their scope as AV tech evolves.

"We have concerns about this technology now — not even considering how complex it might someday become," Chase adds.

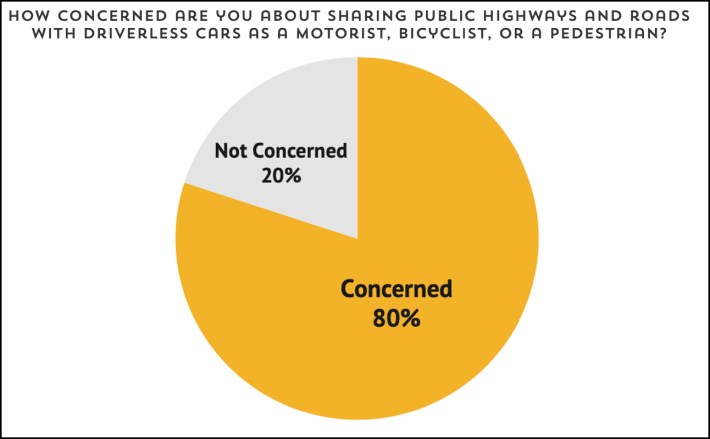

The complexity of today's technology, though, is still a bit of a question mark for most U.S. road users— and Chase says that state and federal governments could be doing more to keep them informed, particularly so they can pressure automakers to do better.

NHTSA's standing general order on crashes involving automated vehicle tech is still relatively new, and large segments of those reports aren't even visible to to the public. California, meanwhile, requires AV manufacturers to submit an annual report to the department of motor vehicles detailing how often their vehicles disengaged from 'autonomous' mode, which usually happens when a human driver is forced to take over in order to prevent a crash. But few other states do.

"[Automakers may face] some accountability now that we have some data, but we want more than that," Chase said. "We want improvements to the standing general order to require more [detail,] and less redaction of confidential business information. Because right now, we don’t even know who’s making those redactions."