Cars equipped with advanced vehicle automation systems are involved in far more crashes than previously known, a new federal report reveals — and automakers should be compelled to provide far more data to federal regulators to provide a clearer picture of the impact of this emerging technology on U.S. roads, safety advocates say.

According to a new analysis from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, automakers reported 392 crashes in just 11 months among motorists who used "advanced driver assistance systems" within 30 seconds of an impact. Advanced systems like adaptive cruise control and pedestrian detection can automatically control a range of common driving tasks, including steering, acceleration, and even stopping a car, albeit only in simple-to-navigate highway environments; about 92 percent of new cars sold today offer at least one such technology, though they're often sold as pricey add-ons and don't come standard across all models.

The growing of prevalence of advanced vehicle technology, though, hasn't been matched by a growing body of data about how those systems impact safety — particularly for people that the drivers of semi-automated cars might strike. Automakers largely aren't required to prove their advanced features are safe for people outside the car before they're sold to consumers, and until June 2021, they weren't even required to report to NHTSA when their tech had been involved in a crash.

(Wonky side note: it's widely believed that NHTSA collected data on crashes during which automated vehicle technology was not actively running at the time of impact because automakers like Tesla often shut off ADAS features less than a second before an impact, giving the false impression that the system played no role in the crash.

Tesla has come under fire from advocates who perceived the move as an attempt to evade liability, but Phil Koopman, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University and expert on automated vehicle safety andexpert on automated vehicle safety, explained that it's perfectly normal for engineers to program a car to override some elements of a vehicle's automated safety features a split-second before an impending collision — e.g. automatic cruise control designed to keep a car moving quickly — but not others, like automatic emergency braking designed to prevent a crash. Put another way: while the package of automated safety features known as "Autopilot" was turned off prior to the Tesla collisions, it's not yet clear that every element of that package was deliberately disabled.)

so... @Tesla was responsible for 70% of autonomous vehicle crashes in the past year? cool cool https://t.co/AXLYl9cp0f

— flat white generation (@blainless) June 15, 2022

In any event, the new trove of data raised particular questions about Tesla, which has become notorious for marketing itself as a path-breaking safety innovator despite a rash of high-profile crashes.

A whopping 273 of "advanced driver assistance systems"-related collisions (69.6 percent) involved the company's vehicles, though NHTSA was careful to note that it's not clear what percentage of ADAS-equipped cars on the road today are made by the popular automaker, or how much their owners drove them relative to other models. Tesla's crash reporting process, which utilizes in-vehicle telematics to automatically send data to regulators, is probably also delivering data to NHTSA much faster than the customer claims process upon which some other vehicle manufacturers rely, and that could skew the stats, too.

NHTSA announced last week that it's expanding its investigation into Tesla's misleadingly named "Autopilot" and "Full Self Driving" "advanced driver assistance" systems to see whether they could be actually causing crashes by lulling drivers into a false sense of security behind the wheel of what they think are fully autonomous vehicles, but aren't. (Both Autopilot and FSD rank as level two on the Society of Automotive Engineers' famous automation scale; only cars that reach level five can be trusted to drive themselves without human interference, and they don't exist yet.)

Experts say the new crash stats signal a clear need to more closely scrutinize the largely unregulated AV giant.

"I wasn’t shocked by these numbers; they were sort of what I expected to see," said Koopman. "[This report has prompted NHTSA to say], 'this smells like smoke; we want to see if there’s fire.' Now that they have this data, they're going to be taking a much closer look."

Koopman stresses that NHTSA should be asking a lot more questions about the impact of ADAS on America's traffic safety landscape — and until it does, the Administration may find itself hamstrung in its attempts to regulate the sector.

That's because, unlike conventional crash tests to see if a car's physical components are likely to harm its occupants when struck, there isn't yet a single, definitive way for regulators to certify that automated vehicle software is safe, nor is there a standard testing method for AV tech that the notoriously underfunded agency can actually afford to conduct. That means that NHTSA basically has to analyze crashes after they happen, and then mandate changes to the technology to prevent future collisions.

"Is NHTSA is going to drive each car a billion miles every time there's a new software release?" added Koopman. "It’s unreasonable to expect that. ... The [Federal Aviation Administration] doesn't even do that for planes."

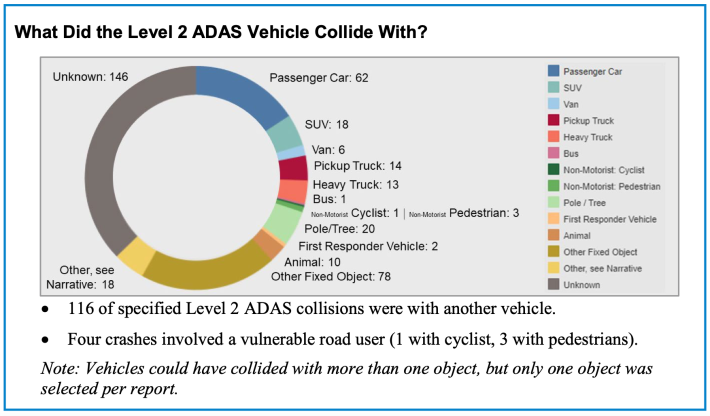

Even the hundreds of real-world crashes in NHTSA's new data set don't give a full picture of what AV tech means for America's traffic violence crisis. It might be tempting to assume, for instance, that ADAS systems are significantly safer than cars driven by human beings for vulnerable road users, given that just 3.4 percent of crashes during the study period involved a pedestrian or cyclist — especially considering that about 17 percent of all crashes between 2006 and 2020 involved active travelers, per NHTSA data.

The trouble is, ADAS systems generally only operate on limited-access freeways where only one-fifth of pedestrian crashes happen; many systems even automatically sense when a car is exiting the interstate and turn the tech off.

Big difference in data quality likely comes from who is operating ADS vs ADAS

— Ken McLeod 🚴🚵🏃🚲 (@Kenmcld) June 15, 2022

ADS is all developers, no self-driving vehicles are sold to consumers

ADAS is consumers, lots of vehicles have ADAS so I was surprised how much Tesla and Honda are represented vs. other manufacturers.

More sophisticated automation systems are being tested in complex city environments, like Waymo and Cruise's notorious "driverless" taxis — and NHTSA found that such vehicle did strike walkers and riders more often than their ADAS-equipped counterparts (11 of 130 reported collisions, or 8.4 percent.)

Still, Koopman says it's too early to draw conclusions about whether or not those cars are safer than human drivers, in part because most vehicles with advanced systems usually still have trained human drivers sitting behind the wheel ready to take over if the system fails. And even when actually "driverless" cars are widely available in U.S. cities,, comparing their safety records to that of human drivers won't be simple.

"[AVs] should be safer than human drivers — but which human driver are you talking about?" he added. "Are you talking about good drivers? If they don't hit cyclists often, well, are they driving in a city that has no cyclists, or a city with lots of them? Are they driving on a foggy night or in the middle of the day? ... Ideally we'd be comparing two vehicles under the exact same circumstances."

To fully grok the safety impact of AV tech, Koopman says that NHTSA should expand its investigation into the industry, and start collecting data every time a robocar makes a mistake. That could include requiring automakers to report minor fender benders, crashes that don't cause injuries or airbag deployments, and any time an ADAS system runs a red light or breaks other traffic safety laws. Requiring police officers to record whether vehicle tech was running in the 30 seconds before a crash — and mandating that automakers make that information easy to access, such as by installing a simple dashboard alert light – is another important step that NHTSA could encourage police departments to take.

Addressing AV safety more comprehensively than that, though, will require cities to think more deeply about designing safe roadway environments where no car is likely to kill. Because at the end of the day, the federal government's safety role is pretty limited.

"NHTSA’s mission isn’t quite to measure vehicle safety — it’s to find problems with vehicle design and make sure they get fixed," said Koopman. "They find clusters of defects, which is different than being the scorekeeper of crashes per mile. We’d all like them to do that, but that’s not really their goal."