Safety researchers often point out that media reports about car crashes tacitly blame victims and erase the systemic causes of traffic violence, convincing the public that nothing can be done to save to lives. Now, an innovative pilot is attempting to stop that harmful trend — by reshaping the language of the police press releases that journalists rely on for their coverage.

A group of 45 police officers from both large and small jurisdictions across New Jersey recently took part in a new study to help understand why so many cops struggle to accurately publicly report all the factors that contribute to deadly and serious vehicle collisions — like the design of the road and the speed of the driver — rather than just a handful of details that might not even be relevant — like whether or not a pedestrian was wearing dark clothing when she was struck.

The researchers behind the study say that framing matters a lot, particularly to time-pressed journalists who don't always have the bandwidth to do their own investigation — or a deep understanding of the structural reasons why so many people die on US roads.

"Time after time, when we were talking to reporters, they’d say, 'Sure, we understand that our language is important, but we’re on such a short deadline — we basically have to report what the police give us,'" said Kelcie Ralph, an associate professor at Rutgers University and a co-author of the study. "We’re sympathetic to that, but and at the same time, we want these articles to get better. So we decided to go upstream."

Some bad crash reporting, of course, comes from the "windshield bias" of police officers who rarely walk or bike. (Other, more familiar forms of bias — like racism — have an impact too, prompting some advocates to argue that law enforcement shouldn't be involved in crash investigation at all.) Ralph and her colleagues say, however, that at as long as cops are writing crash reports, we need to understand why they write them as they do.

The researchers found that some of the reasons are structural. Even big, well-resourced police departments don't always have dedicated crash investigation units, and like journalists, some officers are badly pressed for time in the hours after a collision.

"Basically, a crash happens, and the police tend to release information about it rather quickly — often pretty much as soon as it occurs," said Tara Goddard, an assistant professor at Texas A&M University and co-author of the study. "That makes sense, in some ways; sometimes the police need residents to avoid the area where a crash happened, or they might need assistance in identifying a hit-and-run driver. As traffic safety folks, though, we have different goals, like figuring out what really caused that crash."

Needless to say, those goals aren't being met. Studies have found that U.S. media outlets tend to use problematic, passive language (think: "a bicyclist was struck" rather than "a driver hit a bicyclist"), blame pedestrians rather than drivers even before fault is determined, and treat crashes as unfortunate, isolated incidents rather than as part of a national trend. Fully six years after the Associated Press first advised journalists not to call crashes "accidents," many still do, deepening public misperceptions that traffic violence can't be prevented.

Ralph and Goddard say that's in part because police often focus on individual crash factors that can lead to a fast conviction, rather than on assessing why crashes happen or on how to prevent them. And that can lead them to imply that systemic factors don't matter, particularly when they've never been trained in concepts such as the Safe Systems approach, which became USDOT's national standard last year.

Worse, only 11 percent of the study's respondents indicated that all members of their department received basic communication training, so even well-informed cops don't always have the skills to craft thoughtful messaging.

"Ideally, we want police to ask themselves: what information needs to get out immediately from a public safety standpoint, and what information should wait?" Goddard said. "Because there does seem to be an inclination to immediately say, 'speed doesn’t appear to be a factor,' even before it's actually been investigated."

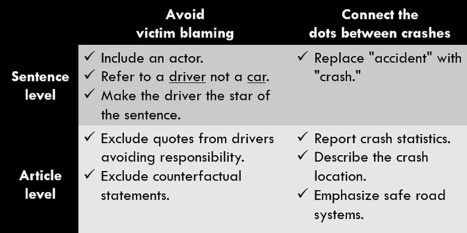

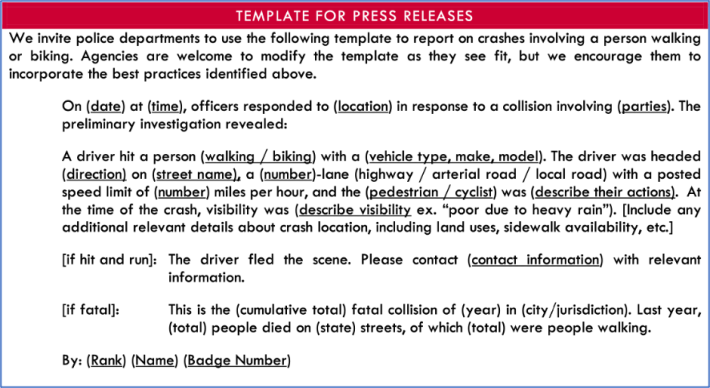

After interviewing the officers, Ralph, Goddard and their colleagues gave their study group a crash course in the many factors that can contribute to a crash, along with some best practices for publicly reporting on traffic violence — and then asked the cops how likely they'd be to act on the recommendations.

Fully 87 percent of cops supported using more active language, such as "crash" instead of "accident." Another 87 percent said they'd reconsider the use of language that de-emphasizes human agency (e.g. "a Ford F150 struck a child," instead of "the driver of a Ford F150 struck a child"), and another 81 percent agreed that police should exclude quotes from drivers, particularly when the people they struck did not survive to speak for themselves.

Ralph notes, though, that the respondents answered the questionnaire shortly after the training, when they may have still felt social pressure to agree with the researchers' suggestions, and she's not confident that everyone had a lasting change of heart.

"We’d talk to people later, and they’d say,' well, speed and quantity of cars on the roadway don’t actually matter! That has nothing to do with crashes!' When, of course, we know they do," Ralph said. "So yes, these numbers are probably overestimates."

The officers were less amenable to suggestions that would have required extra legwork, like reporting on crash statistics (14 percent said that'd be too difficult) or talking about the broader, systemic causes of collisions beyond factual statements such as how many lanes a road had or whether there was a sidewalk (16 percent said that'd be too hard). And 30 percent disagreed with the idea that they should make the driver the "star" of the story, because it might imply that the driver was at fault — even if he was.

"Unfortunately, [research indicates that] the language we currently use blames pedestrians and bicyclists about 75 percent of the time," Ralph added. "Officers were able to recognize that if we switched to language that implies that the driver might be responsible, that might be unfair to the driver. But making the leap to 'the way we do things now might be fair to the person walking or biking' didn’t come as easily.'

Many respondents also worried that even the implication that a motorist might be at fault could expose them to accusations of libel — even though three separate legal scholars told Ralph and Goddard they'd "never heard of press releases being used in lawsuits to hold police or other departments accountable," and that such a statements wouldn't even constitute libel unless they were knowingly false.

"The perception was that they were opening themselves to liability if they shifted responsibility to the driver in any way," Goddard added. "But the same concern wasn’t there for pedestrians and cyclists."

Both Goddard and Ralph stressed that the 45 officers they interviewed do not represent all police, and that further research is needed. And they also stressed that, even if police press releases get better at describing crashes, reporters must do better at interpreting those releases — and that publishers should give them more time, training and resources to do more in-depth coverage, like victim profiles.

In the end, reforming the way police communicate about car crashes is part of rethinking policing more broadly.

"There are lots of very valid reasons why police are under a lot of scrutiny right now, and that's really spilling over into traffic safety," Goddard said, adding, "but hopefully we can all agree that we value safety, including people being able to safely walk or bike without getting killed. If we can start from that place, we might get a little further."