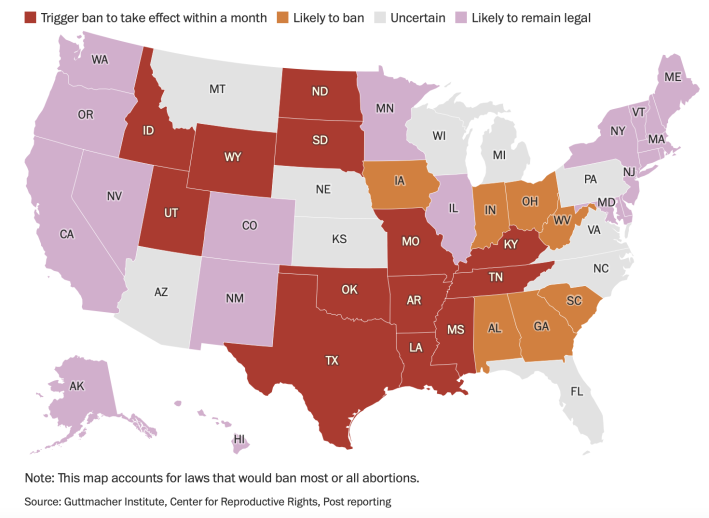

The Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade triggered a cascade of statewide laws on Friday that will increase the average round-trip travel distance required to reach the closest legal abortion care provider from 50 miles to a staggering 250. For some patients in the Deep South and mountain West whose neighboring states have implemented similar policies, those distances will be even longer, ranging from 494 miles in Utah to 1,260 miles in Louisiana — and that's only if abortion-seekers have access to a private car and don't have to rely on the circuitous routes required of intercity bus and rail riders in those notoriously transit-poor regions.

Those distances should be horrifying to anyone who believes in the once constitutionally protected right to bodily autonomy, not least to those who also believe ending America's dependence on private cars is an urgent societal imperative. For some groups, though, those distances are almost certainly a significant undercount — and it's critical for sustainable transportation advocates to confront the reasons why.

Let's make one thing clear: while the average distance to reach an in-person abortion provider before the Dobbs ruling was 25 miles, the average distance a patient actually traveled to access in-person abortion care was 34 miles, in large part because the nearest available clinic on the map either did not, or could not, meet that patient's needs.

Particularly for the low-income, children and teens, people of color, and queer people who are less likely to drive, seeking in-person care has never been just be a matter of finding a ride. It's a matter of navigating medical systems (and even individual doctors) that are racist, queerphobic, and ageist; a prohibitively expensive healthcare system that too often denies life-saving care to those who cannot afford to pay; weak labor protections that make taking multiple days off work to travel to a clinic (and sometimes, endure a mandatory multi-day waiting period) completely infeasible; and so, so much more.

Those barriers were in place long before the Justices effectively quintupled the average distance required simply to arrive at the nearest abortion clinic's doors, never mind the time it takes to actually travel those distances on slower modes like an underfunded city bus.

It also doesn't account for the time it will take to get an appointment at an overburdened clinic — something that even pregnant people in states without trigger laws will have to endure as their local doctors are forced to absorb patients from neighboring communities. A "15-minute city" that requires a patient to make the same trip to her doctor multiple times because that doctor cannot provide her with a service she needs today, arguably, is no 15-minute city at all.

Among sustainable transportation advocates, though, these sorts of non-geographic and non-modal barriers to accessing abortion care aren't often discussed — nor are they talked about when it comes to other basic needs, either.

Despite spilling oceans of ink on the importance of "15-minute cities" where residents can meet all of their daily needs within a short walk, bike ride, or transit trip, many green transportation proponents never truly wrestle with the question of whether residents can actually make use of the essential destinations they can physically reach on green modes — never mind whether those destinations offer the specific services and resources upon which they rely.

That makes sense, to a point. Even the most ambitious land use reform in the world isn't likely to mandate a world-class cancer specialist on every corner, or an opera house on every block, or even a halal, or kosher, or organic grocer in every neighborhood, unless those specific neighbors rally together to demand it. The 15-minute city ideal, it can be reasonably argued, only promises to offer access to a doctor of some kind, some form of entertainment, some grocery store. It isn't even required to offer its residents access to a job within a convenient distance for a green commuter, never mind one at which they're likely to be hired; it must only offer a job center or two, at which a resident might work if they wished to, and an affordable car-share service to access more far-flung destinations not served by the transit network. That's an extremely modest standard, and one which many exclusionarily-zoned American neighborhoods still utterly fail to meet.

Even that modest ideal begins to break down, though, when a community's most common needs aren't being met by its baseline destinations — when the last halal grocer closes in a predominantly Muslim community, say, or when the neighborhood with a huge concentration of children has no pediatrician's office.

Or, to put it another way: Having a few hospitals distributed throughout the city is great, but if those hospitals' doctors either legally can't or simply refuse to provide a procedure that one in four U.S. women seeks by the age of 45 — a number that experts expect to climb even higher now the Roe has been reversed — it's hard to claim in good faith that such a city is accessible to people who don't drive. And when millions of women, transgender men, and pregnant non-binary people are forced to travel hundreds of miles to access abortion care, it's fair to say that America is not just inaccessible to non-drivers: it is openly hostile to a massive segment of its residents, in more ways than one.

I am in no way arguing that the 15-minute city ideal is not worth pursuing. Land-use reform that enables us to build places where people can walk, bike and take transit in their own neighborhoods is not just critical for ending universal car dependency in America: it is necessary, and it is not optional.

The fall of Roe v. Wade, though, offers an urgent reminder that ending car dependency demands that we continually work to dismantle every barrier faced by marginalized U.S. residents when they attempt to access the things they need to survive, live, and thrive. That process of dismantling will carry us far beyond debates about sidewalks, legally allowable SUV size, and zoning codes, and into a total reckoning with the oppressive systems upon which our society is built. And if we don't follow that path, this movement will deserve to fail.