On May 11, 2022, Philadelphia transit officers from the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) were captured on a viral video assaulting and using excessive force toward a Black woman accused of not paying a $2.50 bus fare. The woman was 24-year-old Jocelyn Dallas. The video shows officers beating Dallas about the head, tasing her, and degrading her in broad daylight. After the violent encounter, Jocelyn was charged with assault and disorderly conduct.

What Jocelyn experienced is one of many examples of how public transportation has become an avenue for criminalizing low-wealth and racialized people. Arrests like hers, and the charges and fines that often follow, provide a significant and literal investment in the prison industrial complex in the United States — all under the guise of protecting “public safety.”

How does locking someone up over unpaid traffic tickets or a $2.50 fare increase public safety? How is the response to this supposed "crime" proportionate to the likely impact on Jocelyn’s life and future? What are other impacts, physical and emotional, that Jocelyn may be experiencing after this violence?

A long and violent history of carceral ‘justice’

These questions about the role of incarceration in the transportation realm, though still unanswered, are certainly not new.

In 1994, Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, one of the largest public safety bills in the history of the nation. The bill provided funding for 100,000 new police officers as part of an over $15-billion handout to police departments and their programs. One of the main sponsors of the 1994 bill was then-Sen. Joe Biden who, during his current term in the Oval Office, has since invested $10 billion in increased policing through American Rescue Plan Act funding originally intended to bring much-needed aid to those impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Neither of these policies resulted in significant decreases in crime, but they did have a disproportionate impact on low-wealth and racialized communities. Today, the currently incarcerated population includes a significant number of individuals who have been arrested for a failure to pay debts such as court fees or fines. Failure to pay these fines can become a “failure to comply with a court order” charge that can lead to imprisonment.

Moreover, transportation leaders say that there’s little proof that policing even solves the problems it claims to address.

“We should be focused on increasing ridership, we should be focused on having our stations be great welcoming places, and I don’t see how a ban on busking or panhandling gets us there,” Bay Area Rapid Transit Director Janice Li shared in an interview with SF Public Press. “We don’t have data that shows that fare enforcement increases public safety or has any revenue recovery, but we do have data that shows huge racial disparities on who is impacted.”

What we do know, though, is the devastating impact of incarceration on low-wealth communities for whom public transportation provides the only access to job opportunities, healthcare, food, childcare, and daily necessities. Just like everyone else, these communities have a right to expect that they’ll reach their destination without experiencing brutality or incurring undue fines.

For Black Americans and undocumented immigrants, though, that expectation of basic access is not always met. A recent Transit Center report argued that both groups are disproportionately criminalized when armed law enforcement enforces “quality-of-life laws” like fare evasion or eating on transit.

With a looming recession and rising inflation rates, the economic impact of the pandemic continues to hit many Americans, particularly those of low wealth. The inability to pay for transit fares resulting in brutal violence and criminal charges at the hands of transit enforcement, as it did for Jocelyn Dallas, highlights the need for radical intervention and reimagination across the country.

Our transit agencies have an opportunity to reverse these impacts – and to decarcerate the United States – by removing police encounters and fare enforcement from the day-to-day transit experience. The case of Jocelyn Dallas makes it painfully obvious that decarceration is not only possible through reimagining public transportation, but it is also necessary in a society that claims to have had a racial awakening following the murder of George Floyd.

Not just transit

Of course, transit policing is not the only mobility space where ad-hoc code enforcement has led to the literal and social death of racialized and low-wealth people. For example, on April 11, 2021, Duante Wright, an unarmed 20-year-old Black man was shot and killed by a police officer after being pulled over for hanging an air freshener from his rearview mirror.

Wright’s death is just one of many examples of racial profiling, assaulting, and killing of people moving through space — specifically, Black and brown people who pose no threat to safety — during a “routine” traffic law enforcement activity by police. Philando Castile, Walter Scott, and Sam DuBose were all Black men shot and killed by police after a traffic stop. Sandra Bland was a Black woman pulled over for not signaling a lane change, which led to her arrest and death in jail shortly after the minor traffic violation.

Even removing human officers from the equation can’t completely decarcerate the street realm. In Chicago, traffic camera and vehicle tickets generate millions of dollars of revenue for the city, and disproportionately impact the working poor — particularly Black people — who cannot afford to pay the fines, which in turn leads to spiraling debt, bankruptcy, criminal legal records, and a plethora of other livelihood-threatening punishments from the city and state.

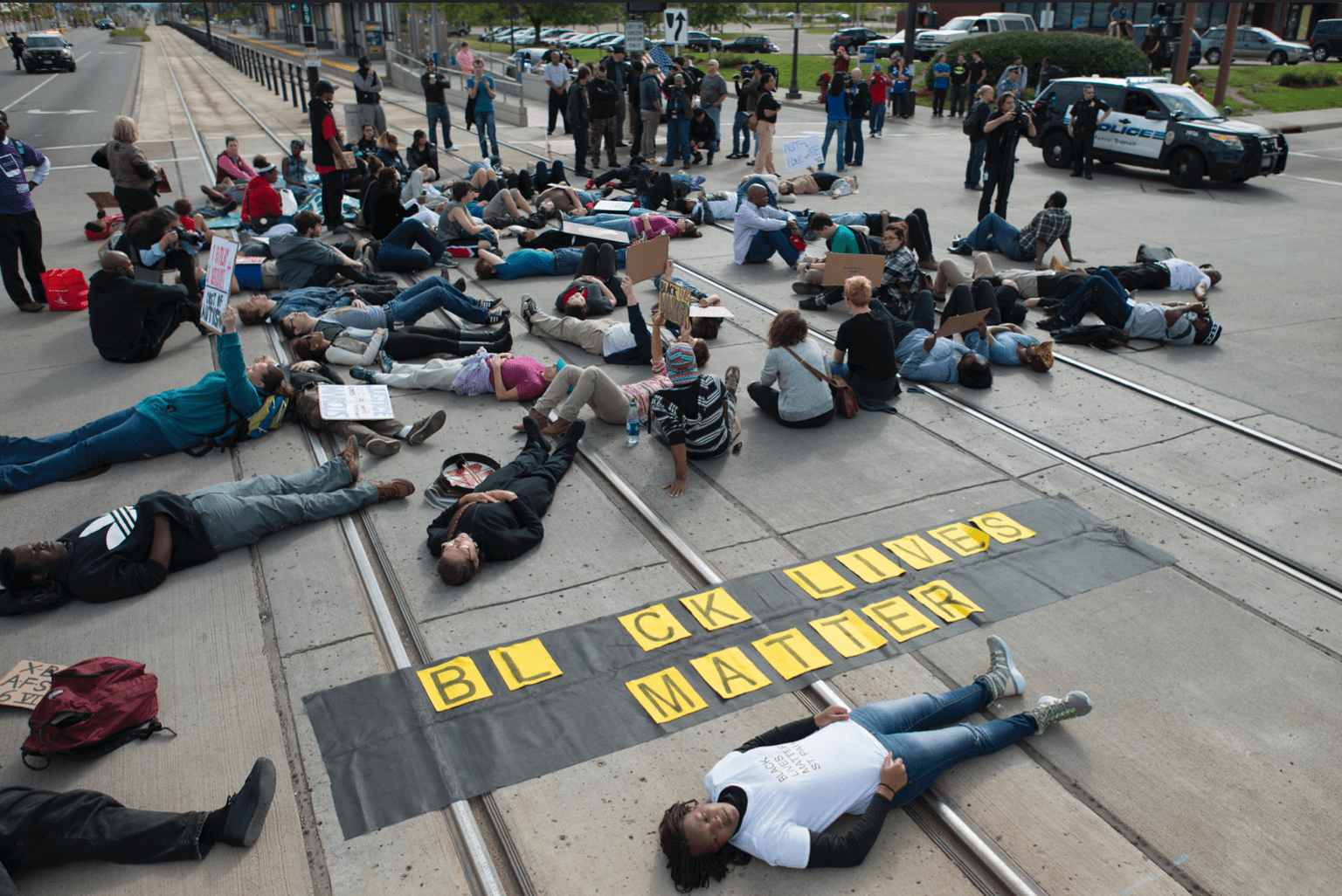

These instances of violence are not an anomaly, but an alarming trend that proves the outcomes of racially biased transportation policing and enforcement activities. Protest, outrage, community organizing, and a new wave of consciousness regarding police violence follow each of these tragic incidents, but to date, the police remain the primary actor in the enforcement of traffic laws for motorists and non-motorists alike.

Hashtags like #drivingwhileblack, #walkingwhileblack, #bikingwhileblack, or Charles Brown’s #arrestedmobility shed light on the many ways racialized people have borne the brunt of transportation policing. And history has shown that when agencies deploy police for fare and traffic enforcement, the most immediate direct outcomes of this disillusioned approach are arrests, excessive force, and incarceration — not safety.

What if public transit actively facilitated decarceration instead of exacerbating it?

An article written by Ben Grunwald defines decarceration as a “massive investment in community infrastructure and an overhaul of criminal justice towards decriminalization, restorative justice, treatment programs, and community control.”

The United States has the world's highest incarceration rate. Decarceration calls for alternative ways of creating public safety and reducing harm. The long-term impacts of decreased mass incarceration, criminalization, death, and degradation of racialized communities will be felt for generations, even if we simply make the decision today to decarcerate through public transit.

To achieve decarceration through public transportation, transit agencies, political bodies, and policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels can start by evaluating the failures and harm of policing over several generations.

Transit agencies can move from a policing model that seeks to detain, arrest, and imprison people to a system that carefully considers accessibility, affordability, mental health, public health, reentry, safety, and healing. Transportation planning can recognize ridership beyond capital interest by considering the physical, economic, and social exclusion that ensues when armed law enforcement, inadequate infrastructure, infrequent service, and disconnected networks become mainstays of the transit experience. A transportation system that aims to decarcerate will prioritize affordability, comfort, access, and ease for the most vulnerable communities.

Here are ways Thrivance Group advocates for implementing decarceration through transit:

- Divest from transit policing. Defund and immediately halt the use of public money and resources to employ police officers to enforce transportation-related laws, conduct, traffic codes, or violations. Reallocate the funds used for transportation-related policing and enforcement to programs such as: free and subsidized transit for low wealth and racialized people, improvement of existing and creation of new transportation-related infrastructure, stations, and amenities, and community-led, place-based transit and neighborhood improvements.

- Reimagine public safety. Fully fund, staff, and implement community-based and impacted community-led public safety, intervention, and healing programs.

- Massive investment in community infrastructure. Public transportation is an essential need for Black and brown communities across the United States. At the same time, it is Black and brown neighborhoods who ??have limited pedestrian infrastructures while also serviced with minimal transit infrastructures (bus shelters, depots, facilities, etc). Learning from the death of Raquel Nelson’s four-year-old son, having the intention of decarceration through transit means providing dignified and functional access to mobility through network design, operations, and infrastructure.

- Expunge past legal records and forgive fees/fines related to traffic- and transit-law enforcement. Decarceration of future transportation-related enforcement must go hand in hand with repairing past harm, which at a minimum should include expungement of legal records and debt forgiveness for past offenses that caused hardship, pain, and financial and emotional burden.

What would it have looked like for Jocelyn Dallas to have her basic needs met? To feel safe? To enjoy using transit? Even in the absence of zero-fare transit, what would a dignified response look like to someone who can't or doesn’t want to pay? What other systems of support and care can we create by decarcerating public transit? How can we prioritize supporting and caring for someone like Jocelyn instead of assaulting and locking her up?

We must answer these questions, and we must envision a future for mobility justice that protects and welcomes those our systems currently brutalize, restrict, and kill. And doing that requires a radical re-imagining of transportation planning and urban planning in general.

Editor’s note: This op-ed was written by members of the Thrivance Group in advance of its 3rd annual Unurbanist Assembly. This virtual free event will take place from Friday, June 17, 2022, at 11:30 am ET until June 18, 2022, at 10:30 am ET. This event is 23 hours long in honor of Ahmaud Arbery and the day he was killed while jogging, February 23, 2020. In alignment with this year's theme of Decarceration as Spatial Reparation, the Thrivance Group is gathering contributions to support one person recently released from the carceral system for twelve months, including the cost of housing, transportation, and groceries.