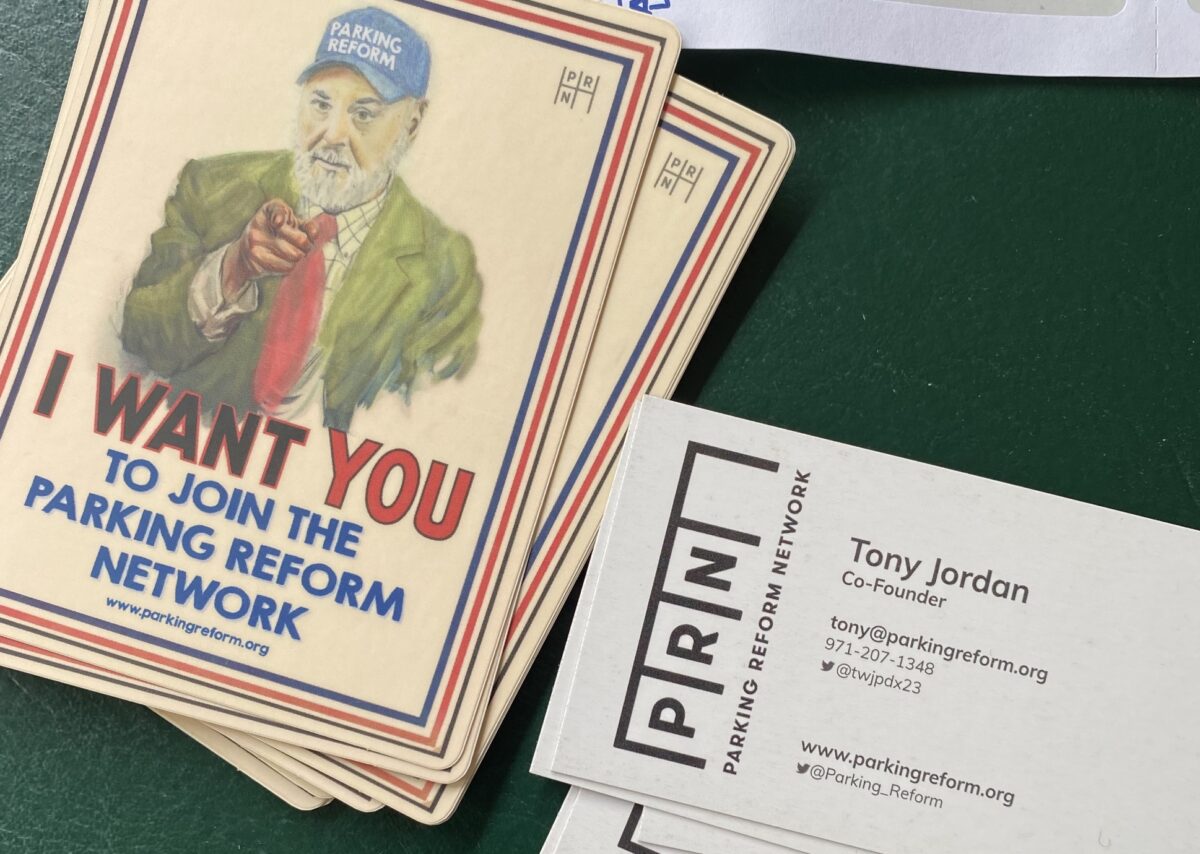

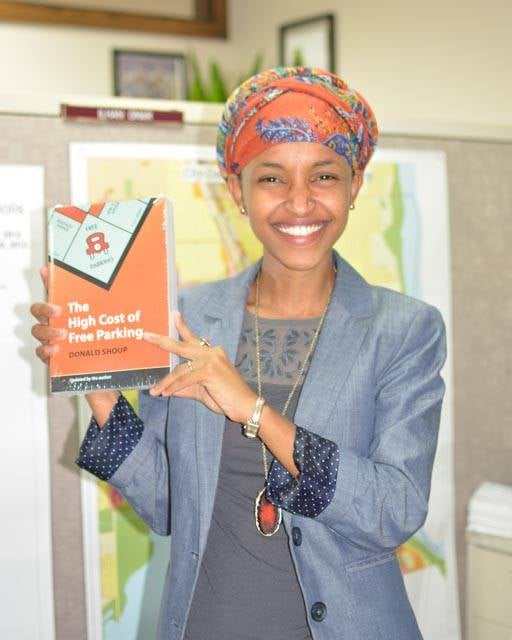

Professor, author, and self-described parking reform “evangelist” Donald Shoup has ascended to the ranks of the most influential urbanists of all time since the publication of his groundbreaking 2005 book, The High Cost of Free Parking, revealed the insidious ways that local car storage policies shape virtually everything about the way cities work — or don't. His equally influential 2018 follow-up, Parking and the City, helped cement his legacy, and turned him into a full-fledged meme.

Now, in a new virtual learning series from Planetizen, he’s bringing his message and signature wit directly to an audience that badly needs to hear it: built environment professionals with the power to push for change. But the videos have something to offer for everyone, from laymen to the most ardent Shoupistas.

We sat down with the Shoup Dogg himself to get a preview of the courses, and to chat about his colossal influence on the transportation conversation. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Streetsblog: You’ve become a massive celebrity among advocates for people-centered places over the years. But in your new course, you said you used to feel like a “bottom-feeder,” because no one thought parking policy was even worth talking about. What has it been like watching the issue you’ve built your career on become a national movement?

Donald Shoup: You know, it’s odd. Back when I started working on this — my first publication with the word "parking" in it came out in 1970 — no one was really interested in it, partly there’s a real status hierarchy among academics who study the city. International issues, national issues, those are seen as important; state issues are a big step down, and local government is just seen as parochial. And sewage and parking are the lowest of the low.

So when global warming started to become an issue people paid attention to, people were looking for all these ways to reduce carbon emissions. But parking escaped them! It tends to get ignored by transportation planners because nothing is moving, and it gets ignored by land use planners because curb parking is in the roadway. Nobody seemed to be taking responsibility for it, so I had it to myself for a long time.

That’s why I say that I was a bottom feeder. But there was just so much food down there. And now, there’s almost a feeding frenzy.

SB: Let’s go back even further. How did we get to a point where most developers have a mandatory minimum number of parking spaces they’re forced to build, and nearly all street parking is free or underpriced?

DS: The thing you have to remember is that cars became popular in American in the early 1900s, but the parking meter wasn’t even invented until 1935. We didn’t have a way to charge for parking, so free parking became the default.

I’ve heard an interesting argument that automobile companies never argued for minimum parking requirements, because they didn’t have to. Everybody wanted them! It wasn’t as if planners imposed them on an unwitting public, because of course everyone wants to park for free if they can, including you and me. But the problem was how much free parking to provide, and it was reasoned that if you’re going to prevent parked cars from taking over the street, you have to provide all the off-street parking that people might demand for the price of zero — so you should just require developers to build it for you.

SB: In a nutshell, how do your recommendations about parking policy differ from that norm?

DS: My recommendations are pretty much the opposite of current parking policy in most places! [Laughs.] For one, I think we should remove all minimum off-street parking requirements completely and let everybody decide for themselves how much parking they should provide. But most cities tend to mandate parking everywhere, and they tell you exactly how many spaces you have to provide before they’ll allow you to open a business or build a house — and it’s mostly based on pseudoscience. Planners don’t know how many parking spaces there should be for a nail salon or a shoe store or a library. But they set parking minimums for thousands of land uses. And I think they’re beginning to realize that they made a colossal mistake.

Then there’s on-street parking. That’s the second big way that I differ from most cities: most of them make it available for free or cheap, and I say that you ought to charge the market price.

So the next thing, naturally, has to do with how cities spend those meter revenues. Meter money tends to go straight into the general fund, and who knows what that pays for? I think the money should go straight out the other side of the meter and fix sidewalks, or clean the street, or in some cases provide free WiFi — whatever will benefit the district.

And then the fourth thing is the idea of parking cash-out. When an employer offers their employee free parking, I say that they should have to offer the cash value of that spot to any employee who doesn’t use it. They can buy a bus pass, a bicycle, anything like that.

SB: It’s intriguing that you’re framing this idea of a parking cash-out in terms of giving non-drivers something, rather than taking something away from people who get around in cars.

DS: Honestly, I’ve given up on the idea of selling people on taking anything away. That’s part of why parking cash-out appeals to me; it gives us a way to say we should give the same benefit that we give people who drive to the people who are now being left out. I could get very self-righteous about how parking policy connects to air pollution and global warming and social justice and transportation justice, and I do harness my ideas to those issues. But it’s sometimes more effective to focus on what parking reform gives us.

I heard [former MassDOT CEO and current deputy administrator for the Federal Highway Administration] Stephanie Pollack speak once in Boston. She was not presenting herself as an expert on parking, but she said something I thought was really clever: "If you want parking reforms, don’t even mention the word parking." She argued that we should be talking, instead, about what’s lacking in our neighborhoods, what residents want, and then you can tell them, "Well, parking revenues are one way to get those things."

At the end of the day, we’re not really convincing people to pay for parking. We’re convincing stakeholders that they want to charge for parking — and to be clear, they’re usually not charging the people who live there, or the people who run businesses there. They’re charging the people who come from outside. It’s like Monty Python’s idea of taxing foreigners living abroad; that’s what parking meters do. And it’s not a tax, it’s just a user charge.

SB: What if cities are ready to take the next step? Are there other ways to use parking policy to incentivize people to make mobility choices that are better for their neighbors?

DS: That’s where we get into parking benefit districts, which I talk about a lot in the Planetizen courses. The idea is, basically, that meter money should be used for improvements specifically on metered streets, so that you’ll see the benefits, right away, of things like more street trees, or street lighting, or even day cares for children. Or you could even just ask the residents themselves what they would like that money to be spent on. That totally changes the conversation, because it turns the parking meter into a cash register for the whole neighborhood.

A good example is Pittsburgh. They already had parking meters, but like a lot of cities, they didn’t want to divert that money away from the general fund because they said they depended on it for other things. But the meters stopped at 6 p.m., even in neighborhoods with a ton of nightlife. So I said, "Well, if you start charging after 6, maybe that revenue could go to pay for public services in the district," and they bought the idea. But the trick was, instead of calling it a parking benefit district, they called it a parking enhancement district. They put in these variable prices so that spaces were never too crowded or too empty, and they went to the neighborhood and said, "If we do this, we’ll use the money to improve this area," and the neighborhood said yes. Over time, it became very popular and they did it in more places.

SB: That’s pretty amazing, considering how emotional people tend to get when any kind of parking reform gets proposed.

DS: I like to joke that when people think about parking, they do it in the reptilian cortex of their brain, the part that makes snap decisions about how to eat and avoid being eaten. We don’t think very carefully about it. Staunch conservatives become ardent communists when they talk about parking! Rational people become really emotional!

But there are so many ways in which we’d be better off if we reformed our parking policy — and we’d be better off tomorrow, not just 100 years from now. Because parking reform doesn’t just help us cut down on greenhouse gas emissions, but nitrous oxide emissions, particulate pollution, traffic crashes, all these benefits. I think urban planners have made epic mistakes in almost all of their parking policies. But now they can fix it.