More and more Americans are believing the hype about electric vehicles — that cars with zero tailpipe emissions will save our society from the ravages of global warming. There are myriad studies out there about how misguided, short-sighted and foolhardy this belief is — but over the past two weeks, four more respected thinkers have weighed in on the subject. Below, we present a digest and links so you can get up to speed on this slow-moving disaster. Taken together, the pieces make a strong argument that we are being sold a bill of goods (and that's even without any of the posts even focusing on how electric cars do nothing to reduce congestion and mobility efficiency). The following was compiled by Streetsblog's Gersh Kuntzman:

Danny Harris, Oct. 7

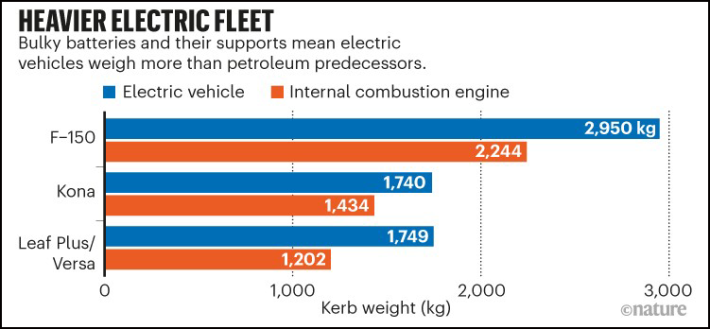

In this piece for Bloomberg, the executive director of Transportation Alternatives focuses on the added killing power of electric vehicles, which often weigh more — especially when the heavy batteries are loaded into frames like the Ford F-150, which is poised to be a true behemoth on our roads.

Here are some excerpts:

While these trucks are reducing the ecological destruction of motor vehicles, they are exacerbating another public health crisis: traffic violence. The auto industry is greening itself by building vehicles that will make our streets run red.

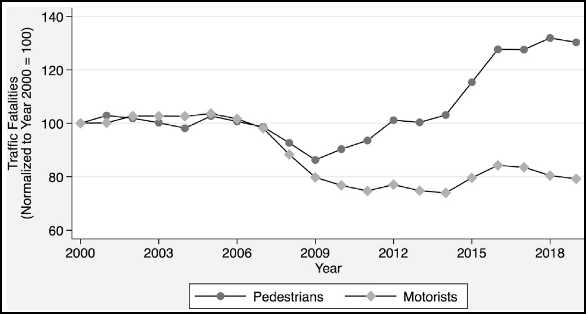

Globally, traffic crashes kill 1.35 million people a year — including almost 40,000 in the U.S. annually, where the traffic death rate has historically been the highest among high-income countries. They are the leading cause of death for children and young people around the world. In the U.S., Black and Indigenous people are especially likely to be killed in traffic crashes, as are older adults and bicyclists. Between 2015 and 2030, fatal and non-fatal crashes will cost the world economy an estimated $1.8 trillion. In the U.S., enormous vehicles are largely to blame for increasing death counts.

As they have expanded in size, they’ve also become heavier. Between 2000 and 2019, the average weight of vehicles involved in a fatal crash increased by 11 percent. One new GMC Hummer EV, for example, exceeds the Brooklyn Bridge’s 3-ton weight limit by 50 percent. Larger and heavier vehicles tend to have longer stopping distances, and hit with greater impact on collision.

A recent study in the Economics of Transportation estimates that if between 2000 and 2019 all light trucks were replaced with cars, more than 8,000 pedestrians would still be alive today.

As car companies scale their electric operations, they should take this moment to build more ethical vehicles — cars that can help save our planet and save our lives. Such vehicles must prioritize the safety of both drivers and those outside the vehicle, especially the most vulnerable — children, older adults, those with limited abilities, Black and Indigenous people, pedestrians and cyclists — above all else.

Blake Shaffer, Maximilian Auffhammer and Constantine Samaras

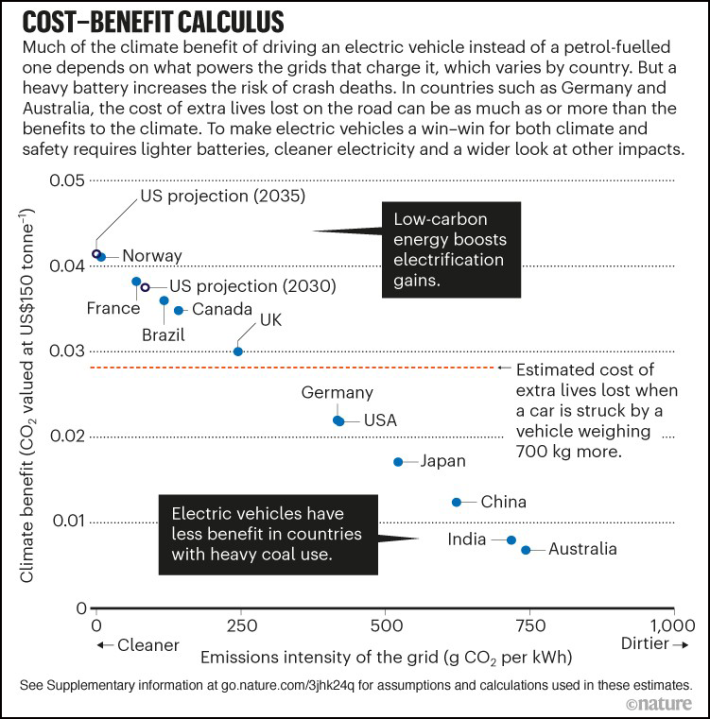

In this piece in Nature, three academics make the argument that the state must regulate electric vehicles and their batteries to "consolidate the gains from electrifying transport." Here are some excerpts:

Electric vehicles are here, and they are essential for decarbonizing transport. [But] one issue that has received too little attention, in our view, is the increasing weight of vehicles. Pick-up trucks and sport utility vehicles (SUVs) now account for 57 percent of US sales, compared with 30 percent in 1990. The mass of a new vehicle sold in the United States has also risen — cars, SUVs and pick-up trucks have gained 12 percent (360 pounds), 7 percent (300 pounds) and 32 percent (1,260 pounds), respectively, since 1990. That’s equivalent to hauling around a grand piano and pianist. Electrifying vehicles adds yet more weight. Combustible, energy-dense petroleum is replaced by bulky batteries. And the rest of the vehicle must get heavier to provide the necessary structural support.

If US residents who switched to SUVs over the past 20 years had stuck with smaller cars, more than 1,000 pedestrian deaths might have been averted, according to one study. Under the energy systems operating in most countries today, the cost of extra lives lost from a 1,540-pound increase in the weight of an electrified truck rivals the climate benefits of avoided greenhouse-gas emissions. Without addressing the weight issue, the benefits for society of going electric will be smaller than they could be in the next decade. (The chart below explains a lot):

Basic economics tells us that activities that impose costs on others should be taxed. Setting registration charges on the basis of vehicle weight can discourage heavy vehicles and encourage light ones. Collecting weight-based charges also addresses another looming problem for governments — lost revenue from forgone petrol and diesel taxes as more electric vehicles hit the roads.

Further developments in battery technology are needed to reduce pollution from manufacturing and to consume less cobalt and other rare metals and minerals. Schemes for recycling and reusing battery and other materials need to be put in place6, before tens of millions of electric vehicles arrive on and then leave the roads.

Reducing the distance driven can help in meeting climate targets as electric and, eventually, automated vehicles become widely available10. Policies should ensure that alternatives such as walking, biking and public transport are safer, more convenient, accessible, affordable and reliable.

Urban designers should consider the impacts of zoning and development on driving patterns to minimize average distances travelled and air-pollution impacts that disproportionately burden vulnerable communities.

Ultimately, to manage climate change, the world needs to stop emitting greenhouse gases from vehicles and power plants. Electric vehicles powered from a clean grid are an essential step in the right direction. A focus on driving lighter, safer, cleaner and less can ensure a better future for everyone.

Eric Jaffe, Oct. 14

In this piece on Medium, the editorial director of Sidewalk Labs also focuses on "the growing size of vehicles" and relied heavily on research by economist Justin Tyndall of the University of Hawaii. Though he does not specifically focus on electric cars and trucks, it's clear that the nation's hunger for bigger and bigger vehicles will continue unchecked if pollution and climate change are greenwashed off the table. Here are some excerpts:

Overall, larger vehicles [are] related to more pedestrian deaths. For the average U.S. metro area, a 220-pound increase in vehicle size corresponded to a statistically significant 2.4 percent increase in pedestrian fatalities. The impact of light trucks (again: SUVs, pick-ups, and minivans) was even more significant. In an average metro area, for every 10 percent of vehicles that rose in size to light trucks, there was a 3.6 percent increase in the pedestrian fatality rate.

But Tyndall did find “some evidence” that larger vehicles improved occupant safety. The result is a twisted arms race where people may try to purchase a larger car to protect themselves, with pedestrians and occupants of smaller vehicles suffering greater fatality risk as a result. In Tyndall’s words, this finding “suggests that driving a larger vehicle offloads fatality risk from the occupants to other road users.”

Tyndall’s research also shows how policy can support design upgrades. The study estimates — in a strictly economic sense — that SUVs would need to cost $750 more to balance out the social risk they create for pedestrian safety. It’s not hard to imagine such fees being routed to cities to help implement complete streets or other policy changes, perhaps through a federal pool distributed by metro area need.

Adele Peters, Oct. 15

In this reported piece for Fast Company, Peters focuses on the weight of electric vehicles, propping up the concerns of the previous two op-eds. Here are some execepts:

Ford’s new F-150 Lightning, the all-electric version of its most popular truck, is more powerful and faster than the previous gas versions of the vehicle, and designed to tempt truck drivers to decarbonize. But the truck is also much heavier, weighing in at 6,500 pounds, or 35 percent more than the gas-powered F-150. That’s mostly because of the enormous battery inside.

Batteries keep improving and getting cheaper; so far, automakers have used those improvements to boost the range and power of their vehicles. But at some point, especially as it becomes easier to find a charger anywhere, it won’t be critical to add more range—most car trips are short, anyway—and batteries could shrink.