The majority of Americans support transportation reform that would reduce our national dependence on automobiles — and better messaging to address skeptics' underlying partisan values could make a big difference in persuading the rest, a new study suggests.

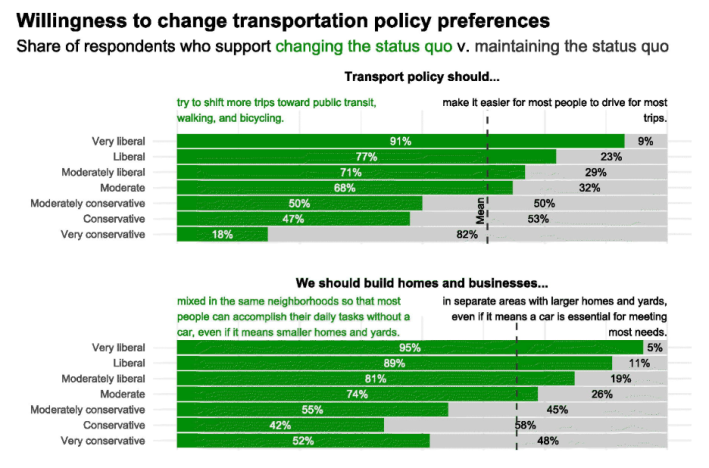

In a viral new paper published in this month's Journal of the American Planning Association, researchers found that 63 percent of U.S. residents support transportation policies that "shift more trips towards public transit, biking and walking," regardless of their political affiliation.

A further 69 percent said they would support reforms that make it possible for most people to accomplish their daily tasks without a car, and respondents were split evenly on the question of whether downtown shopping districts should offer plentiful parking instead of sustainable transportation infrastructure — two findings that might surprise local leaders who assume most of their constituents value convenient driving above all else.

The more left-of-center a respondent was, the more likely he, she, or they was to favor sustainable transportation-boosting policies. But significant numbers of moderates and conservatives were on board, too — and the study authors say that's strong evidence that there's more latent demand for de-centering the automobile than transportation leaders may realize.

"The bottom line is, people do want a different transportation future," said Nicholas Klein, assistant professor at Cornell University and co-author of the study. "I think that's the important takeaway: the status quo is not working."

Klein and his colleagues aren't the first researchers to discover that Americans want more walkable, bikable and transit-rich places than their leaders tend to give them — and they definitely aren't the first to observe that liberals want those reforms the most.

But they are among the first to ask what, exactly, underlies those partisan divides over our transportation future — and what they found could help leaders reach skeptics on every side of the aisle.

Here are four key takeaways.

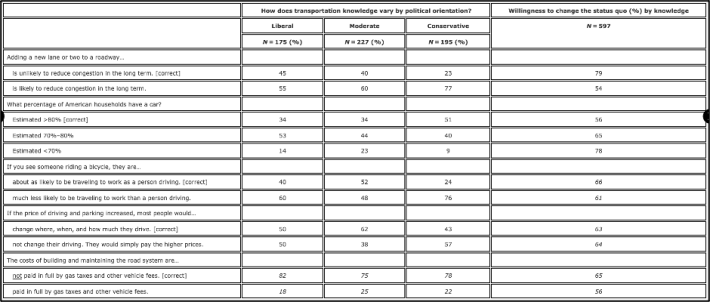

Conservatives are more misinformed about key transportation issues — but liberals aren't much better

Transportation leaders have known about induced demand for nearly a century, but most members of the American public haven't gotten the memo.

Only 45 percent of liberal-leaning respondents correctly guessed that adding a new lane or two a roadway is unlikely to reduce long-term congestion, compared to just 23 percent of conservatives, and 40 percent of moderates — despite the fact that researchers have been writing papers about the phenomenon since 1932.

Conservatives were also more likely to guess wrong on a range of other urban planning basics, too, like the (significant) impact of pricing mechanisms on reducing driving, the (relatively low) prevalence of leisure vs. transportation cycling, and more.

Klein's co-author, Kelcie Ralph, says the results paint a clear picture for the need for better education around transportation concepts.

"We should have articles in every paper and exhibits in every museum about induced demand," the Rutgers University associate professor said. "We’ve just struggled professionally to get the word out. Now, we have to make that our mission. If you know that highway expansion won’t cure traffic, you’re going to be less inclined to let your DOT get away with it."

But the researchers also emphasize that conservatives aren't the only ones who could benefit from more education about how our roads really work — and there may be no better evidence than the highway-focused bipartisan transportation bill wending its way through Washington.

"Given what we found out about how little Americans know about this across the board, the infrastructure bill being debated in Congress is not that surprising," added Klein. "By and large, both the public and government leaders are on board with more road building — because they don’t know any better."

Liberals are more likely to support sustainable modes — but conservatives aren't that far behind

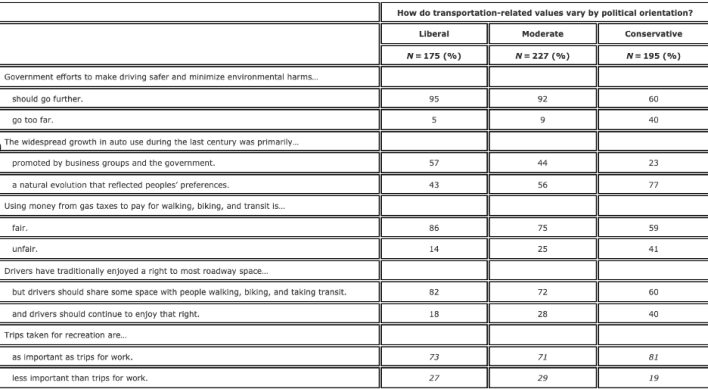

Surprisingly, the only piece of transport trivia that liberals, conservatives and moderates mostly got right was that drivers don't really pay for the roads they use — but not everyone thought that was necessarily unfair.

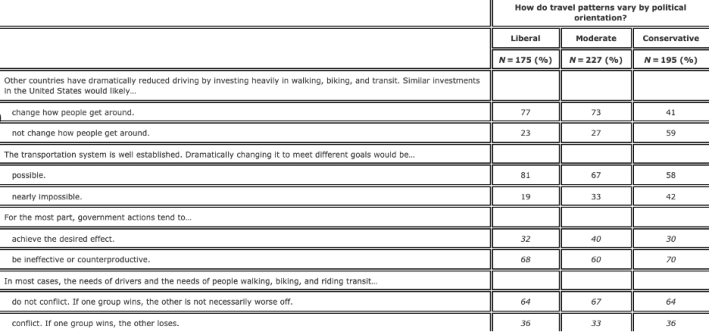

Indeed, on a range of questions aimed at understanding respondents' deepest transportation values, conservatives were consistently more likely to express the idea that diverting money, road space or other resources from driving to other modes was unfair, or that government efforts to preserve the car-focused status quo were a form of harmful overreach.

But interestingly, the majority of right-leaning participants (59 percent) still said that "using money from gas taxes to pay for walking, biking and transit" was the right thing to do — and 60 percent of them agreed both that "government efforts to make driving safer and minimize environmental harms should go further" and that "drivers should share some space" with people on other modes.

That finding may indicate that there's a bigger conservative appetite for transportation change than politicians give their constituents credit for — and that the reason why they might balk at large investments has more to do with what they believe governments can do than what they should do.

"The GOP has been subjected to decades and decades of messaging that the government is harmful and serves us best by getting out of the way," said Ralph. "But if they can [come to believe] change is possible, they're much more likely to support reform. The space for advocacy is to make visible the possibility for change. ... If they can feel it, they can experience it, these efforts are going to be much, much more successful."

Liberals are more likely to think changing transportation is possible — and maybe, conservatives can be shown the same thing

Perhaps the biggest difference between liberals and conservatives that the researchers found was the scale of their imagination.

A staggering 77 percent of liberal respondents believe that the United States could mirror other countries' success in changing how people get around by "investing heavily in walking, biking and transit," while just 41 percent of conservatives thought those investments would make the same impact.

The researchers said that finding underscores the importance of engagement strategies that don't just tell constituents what a less car-dependent life could look like, but actually show them — and many communities have already started.

"We need to show the possibilities of change at the local level, and show what actually happens when we reshape street space," said Klein. "That's where things like tactical urbanism become really important. During COVID, we’ve seen cities open their streets for people walking and biking, and it had a huge impact; it demonstrates, at the local level, the ability of government to do something positive."

Messaging matters

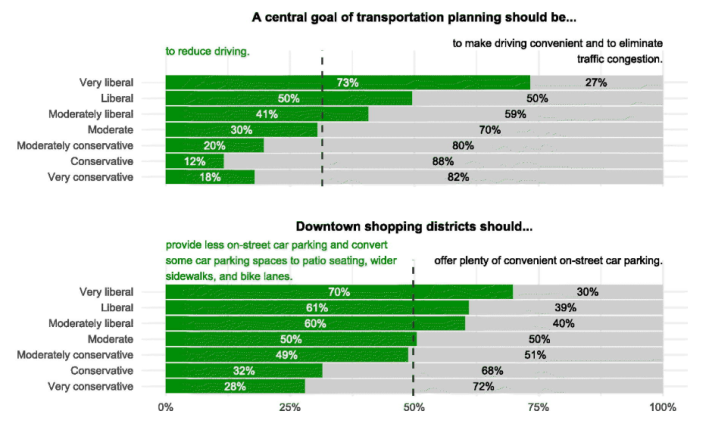

When Klein and Ralph's study first went viral on sustainable transportation Twitter, advocates were quick to point out one apparently contradictory finding: while 63 percent of respondents were on board with mode shift, only 32 percent thought that transport policy should explicitly aim to "reduce driving" — even though cutting car trips is a natural byproduct of getting people to try other ways of getting around.

Really interesting findings about partisanship and transportation policy.

— David Zipper (@DavidZipper) September 30, 2021

An apparent contradiction: A majority of Americans think transportation policy should "shift trips toward transit, walking & biking," but only a small minority say "reducing driving" should be a goal. https://t.co/0jKa41769E

But Ralph and Klein emphasize that this apparent contradiction is actually a powerful insight into the kind of messaging that works for most American — and if leaders want to change hearts and minds, they should focus on what transport reform gives people rather than what it takes away.

"It's really the difference between 'we're waging a war on cars' and 'we're expanding transit, walking and biking,'" Ralph said. "If we say we want to shift trips, it could make things easier in the short term to focus on that positive messaging."

Ralph is careful to note that eventually, leaders will have to level with their skeptical constituents about how reshaping streets will effect their driving commutes — and that deeper conversation needs to be approached with care.

"Sure, we can say, 'All we’re doing is adding transit, walking and biking amenities.' But when push comes to shove, we know that budget is limited, and driving will be reduced [by these policies]," she added. "There may be advantages to being honest about that and having that hard conversation, at least when the time is right."

But Klein emphasizes that leaders don't have to choose between selling the power of sustainable transportation and having honest conversations about the dangers of autocentricity — and to reach a majority of Americans, they should use a bit of both.

"More radical messaging and more accepting messaging can work together," Klein adds. "Because at the end of the day, there’s a broad support for lots of these policies — and it's a lot broader than pundits and policymakers seem to think. These reforms are popular, and especially if we focus on liberal and moderate support, there’s a lot of room to make big moves. If we focus on the negative messaging we get from a small number of conservatives who happen to have a lot of influence in policymaking, we’re focusing on the wrong part — and we're missing the overwhelming support for change."